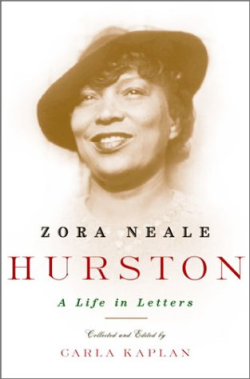

Carla Kaplan,

editor of

Zora Neale Hurston:

A Life in Letters

.

_____

.

Alice Walker’s 1975 Ms. magazine article “Looking for Zora” and Robert Hemenway’s 1977 biography reintroduced Zora Neale Hurston to the American landscape and ushered in a renaissance for a writer who was a bestselling author at her peak in the 1930’s, but died penniless and in obscurity some three decades later.

Since that rediscovery of novelist, anthropologist, playwright, folklorist, essayist and poet Hurston, her books — from the classic love story Their Eyes Were Watching God to her controversial autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road — have sold millions of copies. Hurston is now taught in American, African American, and Women’s Studies courses in high schools and universities from coast to coast.

In Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters, Hurston scholar Carla Kaplan has meticulously edited and annotated a landmark collection of letters that provide a penetrating and profound portrait of her life, impressive imagination, and writings.* She joins Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in a December, 2002 conversation about Hurston, one of the most brilliant contributors to American letters.

.

.

.

___

.

.

photo by Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress

Zora Neale Hurston, 1938

.

“You are right in assuming that I am indifferent to the pattern of things. I am. I have never liked stale phrases and bodyless courage. I have the nerve to walk my own way, however hard, in my search for reality, rather than clink upon the rattling wagon of wishful illusions.”

From a Zora Neale Hurston letter to writer Countee Cullen, March 5, 1943

.

__

.

JJM The book is an exquisite labor of love. What did Zora Neale Hurston mean to you prior to undertaking this work?

CK I first encountered her in one of the first seminars I ever took as a graduate student, and the first book I read, like so many people, was Their Eyes Were Watching God. As a student of literature, that novel was extraordinary to me. It was one of the first books I had ever seen that in a contemporary way completely rewrites the quest for romance from a feminist perspective. It is about a woman’s search for fulfillment, which was an amazing thing for a black woman to write about in 1937. According to the mainstream culture of the time, your life was not supposed to be about fulfillment, it was supposed to be about barely getting by. Hurston took the novel and completely reshaped it as an African American woman’s fairy tale for fulfillment. I just thought that was an incredible thing.

I began looking into her other work and discovered the folklore, and found it amazing that her interests extended beyond personal fulfillment into documenting her culture in a way that almost nobody else was doing in the twenties and thirties. Early on in my discovery of her, I had occasion to look at her letters, and I thought they were some of the most beautiful letters I had ever seen. Then I discovered that, with one exception, there had been no publication of an African American woman’s letters. I found that to be remarkable because in literature we think about the ways in which people use private forms — like the letter or the journal — to say something they can’t say in the public sphere, and to confide things to an audience they can select and choose. I thought that if there was ever a group of people who had to have recourse to that private form of communication, it would be black women, but I learned there had been no book of letters by an African American female writer, artist, dancer or intellectual ever published. Since Hurston was one of the last twentieth century people to understand the form of the letter as a true art, I thought it was time that this happened.

JJM In his foreword to your book, Hurston biographer Robert Hemenway writes, “What emerges most strongly from Hurston’s letters is the force of her personality.” Were you surprised by anything you discovered about Hurston during this process?

CK Constantly. The process was much more one of surprise than one of confirmation. Before I even started to locate and collect, my first goal was to learn everything about her that I possibly could. I read every biographical treatment, every sketch, and everything else I could get my hands on, so I thought I knew something about her. However, then I started reading her letters, and in them discovered a different Hurston than the one we have known until now because it is really only in her letters that she is, in many cases, free to say what she really thinks. For example, there is a rather extraordinary letter where she writes of being so disappointed in racist culture that she can now understand militancy and violence for the first time. That is a Hurston that we have never seen. There is no other public record of that tenor. She was very careful to create a persona that was not angry. It was very constructive and it was very strategic because she knew, as a black woman in the thirties, if she exhibited her rage she would have no venue at all. But in the letters we see her essentially say, “What am I going to do with my anger? Where am I going to go with it?” So, that was one element that surprised me.

JJM In general, were her views on race known before these letters?

CK Interesting question, because her views on race were so complicated. I think we knew how complicated they were, but I think we haven’t seen her feel them until the letters. She was a trained anthropologist in the Franz Boas school of anthropology, and was in one of the first groups of intellectuals that we now call the “social constructionists” — people who think that there is no such thing as race. Boas was one of the first intellectuals to make that case and she was very much of that school, as were many members of the Harlem Renaissance, who were, well before the 1980’s, making the case that there was no such thing as race. Basically there was construction essentially of a racist culture meant to tear people apart and to create false boundaries between them. Like many of her colleagues in the Harlem Renaissance, she holds to that intellectual view.

At the same time, as an artist and as an anthropologist, she believes in race. She believes in something she called her “blackness,” her “Negroness,” and she devotes an enormous part of her own intellectual career to documenting and recording and collecting and saving it. That contradiction is not hers alone. That is a contradiction you find throughout the Harlem Renaissance and after. While we knew this about her intellect, the letters allowed us to now see it at work. On the one hand she writes about race as a fiction in certain pieces, and on the other hand, an essay like “Characteristics of Negro Expression” makes an attempt to document the distinctiveness of black culture. In the letters, you see it happen almost sentence by sentence. She will say race is a bunch of nonsense, and then she will say to Langston Hughes, “Don’t you just love black things?” I love that in the letters. So, her views on race were pretty much known, but what it felt for her to live those views during that moment in American culture, I don’t think we knew that prior to the letters.

JJM How did the time of the Harlem Renaissance allow Hurston to advance her personal artistic goals?

CK It did allow her to advance her goals, although at the outset it was very constricting for her. On the one hand it created a community of fellow and often like-minded intellectuals — Langston Hughes, Dorothy West, Helene Johnson James Weldon Johnson, Bruce Nugent — in which to work. It also created, as some of her peers derisively called it, “the vogue in all things black.” There were publishing venues for one of the first times, and in that way it helped her advance her work. However, her own goals were really eschew of those of most of the others in the Harlem Renaissance. Everybody else was trying to create New York, Chicago and Washington, D.C. as the centers of all interesting things. She was not interested in that. She is interested in rural, southern, illiterate black culture. This is not what her peers in the Harlem Renaissance were documenting. In many ways she is on the outside of the central topics, and it made it hard for her. That is part of the reason she didn’t publish in the twenties when everyone else was because she was interested in a different milieu, and she was interested in them for different reasons. Also, her relationship with her patron during the Harlem Renaissance was extremely constricting economically and legally. She actually didn’t own any of her own productions from 1927 – 1932, which were the most important years of the Harlem Renaissance. So, much of her work was on the side and actually after the fact, which may have been useful anyway since the subject matter she took on was on the outside of that written by others of the time.

JJM It was a short story that inspired a publisher to ask her if she had any novels.

CK Yes. The publisher was quite impressed and wrote back, asking if she had a novel. Never missing a beat, she replied that she had, and proceeded to write one in about seven weeks. But, she was writing during all that period. Oddly enough, her first venue in the twenties was poetry, almost none of which has seen the light of day. That is not an enormous loss — poetry is not her best venue, as it turns out. She then turned to short stories and theatre, all written during the twenties, probably because she could write them in between the other things she was doing. It wasn’t until the thirties that she turned to the folklore and to the novel. She skips genres almost every decade. In the forties and fifties she turned to essays and to non-fiction.

JJM Writing about politics?

CK Yes, she does a little throughout, but not seriously until the forties.

JJM She and Langston Hughes had a celebrated dispute concerning artistic integrity that ultimately ruined their storied friendship. Do these letters shed any light on this dispute?

CK The letters clarify that it didn’t completely ruin their friendship. What we always thought was that the controversy surrounding who wrote the play Mule Bone ended their friendship. The letters, however, seem to tell us it didn’t quite end the friendship. When Hughes’ autobiography The Big Sea came out, which included a rather aggressive final section on her, she wrote to mutual friends of theirs, telling them she was going to review it. By all accounts her review would have been quite favorable. We also know from the letters that when she was accused of an absurd morals charge involving the alleged harassment of a ten year old boy, Hughes admitted a willingness to testify on behalf of her character. So, while the contentiousness over Mule Bone existed, the friendliness between them did not stop.

JJM Charlotte Osgood Mason was benefactor to both Hughes and Hurston. Did Mason take a side in this dispute over Mule Bone?

CK The relationship between Mason and Hughes at that point was virtually over. The Hurston letters certainly make it appear that Mason was taking her side and her view. It could be that Hurston was being very cagey in her letters to Mason, feeding her the perspective she wanted Mason to have, or it’s possible she was confirming Mason’s perspective. Mason was also pretty much only given Hurston’s side. If the only version of events in this saga is Hurston’s, Hughes looks terrible. If the only version of events are Hughes’, Hurston looks terrible.

JJM Are there letters from Hughes to Hurston during this period?

CK Yes. The best place to see them is in a wonderful edition of Mule Bone that Henry Louis Gates, Jr. edited within the last ten years. It has all the relative Mule Bone correspondence as the controversy was unfolding. In my book there is other correspondence that refers to it even twenty years later. It was very upsetting to people — and not just for Hurston and Hughes.

JJM Hurston’s review of Hughes’ The Big Sea you spoke of earlier…Was this ever written?

CK As far as I can tell, it was never published because it doesn’t show up in her papers, but she may well have written it.. What we have may be as little as half of what she wrote. She wrote to Fannie Hurst in 1940 saying that she was about to write the review, so it is quite likely she did. She wrote constantly and had an enormously productive, vigorous and disciplined writing life. That is the other thing that the letters show, how incredibly disciplined her career was.

JJM Did her letters change as they went from being hand to type written? Did she open up a bit more? Did she seem to embrace that technology?

CK She liked the typewriter a lot, and frequently talked about her own typewriter. I think she enjoyed typing more than she enjoyed hand-writing. She typed whenever she could, and whenever she had to pawn her typewriter — which she did periodically throughout the twenties and thirties — she talked about that in her letters. She would say she is missing her typewriter, and whenever she got it back out of hawk, she would celebrate the fact that she had it back with her. Friends of hers whom I interviewed talk about how careful she was with the typewriter. Photographs indicate she set it up almost honorifically, displayed in the center of the room. Sheriff Patrick Duvall, the person who saved most of the papers we have of Hurston’ s, talked about the horror of seeing her typewriter buried. Some of her papers were burned and some of them were buried, which was very typical of how personal effects were dealt with in Florida. There has actually been some talk on the part of a few people who are trying to do a treasure hunt to pull that typewriter up.

JJM In 1947, Hurston wrote to her Scribners editor Burroughs Mitchell, “You know yourself that a woman is most powerful when she is weak. Men were willing to do a thousand times more for Mary Queen of Scots than for Elizabeth, and Lizzie so well knew it. All a woman needs to have is sufficient allure, and able men will move the world for her. I am convinced the male gland produces something that puts him out ahead of the most brilliant woman in constructive ways. I mean of course an intelligent man. In the arts it is different. But no woman has ever topped the best man in any of the professions like Medicine, Law, Architecture, Engineering, etc. Nor have any “strong” women inspired that kind of love to make him get out and do it. He fights like a tiger to protect some alluring, weakly thing. Even the men whom Elizabeth advanced were ready to desert her for Mary.” Was this a view she consistently held throughout her life?

CK I have to say I don’t think it was. Burroughs Mitchell, remember, is a very powerful white man. The letter was written in 1947, during the time when she is losing most of her publishing venues. Things are not going her way, and she had great difficulty finding publishers who would take her work she is most proud of — the theatre work and the unpublished novels. So, Mitchell is an extremely powerful white man and she is saying what she believes he wants to hear. The thing I believe she does mean in this very bitter letter, is that she thinks men have no real respect for strong, powerful women – in other words, for their peers. She knows she is a match for any man. She knows she is every bit as brilliant and every bit as powerful and every bit as capable, and I hear personal bitterness in that. That is not what men want, romantically or domestically. They desire weak women. I hear her talking about her frustrations as a heterosexual woman, and as a brilliant woman.

JJM She was pretty candid in her letters in general to Mitchell. Given Mitchell’s position as a white man of power, it is interesting how open she was with him about her views on race.

CK One of the things that is amazing about her and the content of the letters is that she will placate at one moment, and then become quite frank the next. I think the letter you read from is quite bitter and playfully flattering at the same time. So, there is incredible frankness about what it is like to be a woman of her rather extraordinary level of brilliance and accomplishment in a world where that is not respected. She is very frank about that. On the other hand, I don’t think she is being frank when she says no woman’s accomplishments will ever measure up to what man’s. I don’t think you can be Zora Neale Hurston and really believe that. She knows she is a genius, and talks about it in a number of her letters. She writes to Langston Hughes and says she plans to be the “Queen of Conjure” and wear the voodoo crown. She knows who she is. This is a woman who opposed, in some ways, the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, not because she is anti-integration — which she is not — but because she thought it was condescending. That is how strongly she knows who she is.

She didn’t want to be patronized or condescended to in any way. Even when she writes to Charlotte Osgood Mason, she is perfectly capable of being obsequious and an incredible flatterer, virtually at a Uriah Heep kind of level. She doesn’t hold to that, because she will switch back to being herself a moment later. That is why the letters are so amazing. I really do see her as an early feminist at a complicated moment, without the support of a feminist movement. To be a feminist during the Harlem Renaissance put her in a minority position. It was a very male dominated movement and it was organized around a lot of masculine values. Bottom line is I just don’t see her as serious in that letter to Mitchell that you quoted from.

JJM After reading her quite modern day conservative viewpoint on race, the quote read as a conservative view of women as well.

CK I just read it is ironized, as tongue in cheek. Of course, this is always the problem with Hurston. When do you read these things as ironic and when do you not? It is likely some people will read the letters that are signed “Your Devoted Pickaniny,” and will see her as pandering, as playing the minstrel figure. I don’t. It is up to us to judge what is there. My Hurston is a feminist. She is also a political conservative at the end of her life. I will cede that point!

JJM She wrote to her ex-husband, Herbert Sheen, “Love should not last beyond the point where it is pleasurable.” She endured three very unusual marriages. Did she desire a normal, lasting relationship?

CK Interesting question, and now we are “psychologizing,” ok? Everything I am about to say about this is with the caveat of “I have no idea.” I believe that in a sense she was more disappointed not having a lifelong best friend than she was by not having a “normal romance.” I think her views on romance were incredibly contemporary, and what she wrote to Sheen was something she was pretty serious about. She would not stay in a situation of any kind that was no longer working, whether it be professional, housing, or romance. If it didn’t work, she moved on. At the end of her life, I see her isolation much more as someone in need of a best friend who could understand her — male or female — more than a need for a normal marriage. It is really clear that in at least two and perhaps three of her marriages, when they didn’t work, she was the one who walked from them. The problems for her were finding workable friendships. She was so complicated and so self-contradictory in some ways, that finding people who could take in all the pieces was pretty hard for her.

JJM There was an interesting friendship she had with Carl Van Vechten.

CK Yes. He was the most consistent and loyal for her.

JJM When she was at her lowest, during the time she was accused of a bizarre child molestation event, she admitted to him that she was contemplating suicide. I only recall seeing one other letter from her to him after that. What happened to their correspondence after that?

CK Not clear, and it is an interesting question, because for all we know, it may have turned at that point to the telephone, which was becoming more and more technically reliable. Their friendship didn’t end at that point.

JJM So, it is not like she was embarrassed by admitting to her thoughts of suicide?

CK I don’t think so, although that wouldn’t be out of character. She was interesting in that way. When she confided too much, sometimes you could see that she would pull back afterwards. My own sense is that they stayed friends for quite some time and it may not have been through letters.

JJM Zora Hurston was frequently betrayed by the black press. Why?

CK I have struggled with that very question. In some ways she was targeted, and I have to say she became paranoid about the press toward the end of her life, and saw herself as victimized even when she was not. She had to take some responsibility for being a target of the black press because she created a flamboyant and public persona. She hated being in the limelight, yet put herself out there in it. She did things that may have really angered the press.

If you go back to what I was saying earlier about her being a feminist during the Harlem Renaissance, and look at some of the documents that were internally circulated in the twenties among black artists and intellectuals, there was a very specific call on the part of the black press for people to avoid discussions of black sexuality — particularly black female sexuality. That attitude was seen as necessary to counter white racist stereotypes of black female licentiousness that had been going on since slavery — stereotypes that had become a justification for attacks on black women. Most of her peers are saying that what she openly discusses are taboo subject matters that can’t be treated safely in a white racist society. In fact, there are some literal, printed guidelines for black contributors meant for internal circulation, one of which by George Schuyler, who says to stay away from the erotic and from black female sexuality. So, it is an era of those kinds of warnings, and here is Zora Neale Hurston writing a book like Their Eyes Were Watching God, which turns completely on a sixteen year-old black woman’s visualization through the metaphor of a pear tree, of orgasm. Clearly, she is doing some pretty wild stuff, particularly in her milieu and in her context.

She wrote about rural southern blacks at a time when it was thought best to counter black stereotypes by demonstrating how similar black society is to white society, that there is nothing to fear between the races. She does just the opposite, showing white America how different black America is. Given the fact that this was during the height of the Klan, it was a very high risk, aesthetic move. In its context, it enraged many people and was politically very risky. You put that together with the fact that she was a contradictory, flamboyant personality, and she became a very easy target for the press.

JJM She seemed to have very little wiggle room with them. Her view as reported by the World-Telegram concerning Jim Crow segregation was clearly taken out of context. The time she was outrageously accused of child molestation, the black press wouldn’t help her communicate this obvious injustice.

CK Right. Again, she was so iconoclastic that she was a very easy target, and she pissed a lot of people off, quite frankly.

JJM She felt the answer to what went on politically in her contemporary world was as a result of events that occurred in the first century, B.C. She spent much of the later years of her life attempting to communicate this through her story of Herod. Ultimately the story was shot down. How did she lose such obvious touch with her readers?

CK Why and how she lost touch are very interesting questions. During the forties she is writing novels that no one will publish, and writes about this in her letters to Jean Parker Waterbury. By all accounts, her readers and her publishers in that period were dead wrong, and she was dead right. In other words, if we had those novels now, based on the tiny pieces we have of them now, we would be talking about them as works of extraordinary genius and as masterpieces. What would we give now for a novel by Zora Neale Hurston on the life of the first black female millionaire, Madame C.J. Walker? The book’s idea was brilliant, yet nobody would touch it. Yes, she eventually lost touch with her readers but she was on the right track at first.

She may have eventually ended up on such a wrong track out of disappointment in that forties period, because the problem with the “Herod” book is that it is not a great book. By the way, about two-thirds of it exists at the University of Florida Gainesville, beautifully preserved in Mylar sheets with each paged burned down the right side. While Herod doesn’t work as a novel, you have to wonder if part of her losing touch with her readers was a result of her being pushed beyond comprehension. She had done these incredible things no one was interested in, and as a result she started flailing, in essence, and lost touch.

.

.

___

.

Zora Neale Hurston:

A Life in Letters

Edited by

Carla Kaplan

.

___

.

JJM Who was your childhood hero, Carla?

CK The question stumps me a little, quite frankly, because I don’t think I had a childhood hero. I was raised by very progressive parents who taught me that most great achievements are collective works. They felt that people who do great things are “rounding up” collaborative and collective efforts around them, giving them a final step forward. That is not to say certain individuals don’t do extraordinary things, but there is always a group of people behind them that ultimately inspires acts of heroism. Having said that, I grew up admiring some pretty extraordinary people like Rosa Parks, Emma Goldman, and Paul Robeson. But I didn’t have a single childhood hero, ever.

.

.

Interview took place on December 10, 2002

.

.

.

* Text from book jacket

.

.