.

.

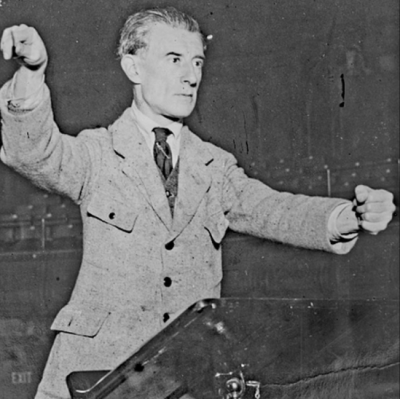

Brad Snyder

.

…..Upon being traded to the Philadelphia Phillies in 1969, Curt Flood, an All-Star center fielder for the St. Louis Cardinals, wanted nothing more than to stay with St. Louis. But his only options were to report to Philadelphia or retire. Instead, Flood sued Major League Baseball for his freedom, hoping to invalidate the reserve clause in his contract, which bound a player to his team for life.

…..Flood took his lawsuit all the way to the Supreme Court, and though he ultimately lost, his decision to sue cost him his career and a chance at the Hall of Fame. But Floods place in baseball history, like that of Jackie Robinsons, extends far beyond his accomplishments on the ballfield. Just three years later, the era of free agency that all professional athletes enjoy today became a reality.

…..Flood took his lawsuit all the way to the Supreme Court, and though he ultimately lost, his decision to sue cost him his career and a chance at the Hall of Fame. But Floods place in baseball history, like that of Jackie Robinsons, extends far beyond his accomplishments on the ballfield. Just three years later, the era of free agency that all professional athletes enjoy today became a reality.

…..In A Well-Paid Slave, the first extended treatment of Flood and his lawsuit, Brad Snyder examines this long-misunderstood case and its impact on professional sports. He reveals the twisted logic and behind-the-scenes vote switching behind the courts decision and explains Floods decision to sue in the context of his experiences during the civil rights movement.#

…..In a February 25, 2008 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician contributor Paul Hallaman, Snyder talks about this story that speaks to fans of sports history, legal affairs, and American culture.

.

.

*

.

.

.

“Floods trade from St. Louis to Philadelphia reawakened latent feelings of unfairness about the reserve system. His eventual decision to act on those feelings led to the first in a series of fights for free agency that altered the landscape of professional sports. Like his hero, Jackie Robinson, Flood had the courage to take on the baseball establishment. In 1947, Robinson started a racial revolution in sports by joining the Brooklyn Dodgers as the 20th centurys first African-American major leaguer. Nearly 25 years later, Flood started an economic revolution by refusing to join the Philadelphia Phillies. The 31-year-old Flood sacrificed his own career to change the system and to benefit future generations of professional athletes. Todays athletes have some control over where they play in part because in 1969 Flood refused to continue being treated like hired help. But while Robinsons jersey has been retired in every major league ballpark, few current players today know the name Curt Flood, and even fewer know about the sacrifices he made for them.”

.

– Brad Snyder

.

*

.

Listen to Sam Cooke sing “A Change is Gonna Come”

.

.

__________

.

PH On October 8, 1969, on the verge of a $100,000 contract, St. Louis Cardinals center fielder Curt Flood — a participant in three all star games and the winner of seven golden gloves — is traded from the Cardinals to the Philadelphia Phillies. He didn’t want to go to Philadelphia but he had no choice. If he wanted to play baseball, he would have to do so in Philadelphia

BS That’s correct. The Cardinals did not consult Flood, he simply got a phone call from a mid-level executive who basically told him he had been traded along with Tim McCarver for Dick Allen, and that they were to report to Philadelphia. They had no choice in the matter.

PH Would you explain the reserve clause and how baseball was able to retain the exemption from the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1922?

BS Baseball’s reserve clause started in the late 19th century because players were changing from team to team and the leagues were folding. In order to create some sort of league stability, they reserved a set number of players for each team. It started out as only a handful of players, but it eventually evolved into entire teams being reserved. That was challenged several times — court cases came down on both sides about whether the reserve clause was an illegal restraint of trade or monopolistic practice.

The Sherman Antitrust Act was enacted in 1890 to prevent contracts or combinations that were a restraint of trade. But in 1922, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that baseball was not interstate commerce, it was intrastate commerce. Holmes wasn’t a baseball fan, and considered the sport to be a series of exhibitions rather than a national business. Television didn’t exist, radio was in its infancy, and there were no minor leagues, so all the interstate workings of baseball weren’t there at that time. Since Holmes said baseball was intrastate commerce rather than interstate commerce, Congress could not regulate it, and baseball was therefore exempt from the Act, which in effect made baseball exempt from the antitrust laws. In 1953, a minor leaguer named George Toolson sued under the antitrust clause. The Supreme Court took the case and ruled that they would not re-examine baseball’s exemption, saying that baseball had an express exemption.

PH Curt Flood came into the story in 1956 …

BS Yes, that was the year he graduated from Oakland [California] Technical High School, and it is when the Cincinnati Reds offered him a $5,000 contract, with no bonus, to play for them during the coming season. Curt signed the contract, but little did he know that when he signed that $5,000 contract, he had also signed his life away, because, in effect, he became a piece of property owned by the Reds forever, and the Reds could do whatever they wanted with Curt’s contract. So two years later, after Curt had two fabulous minor league seasons in the Jim Crow South, the Reds traded him to the Cardinals, but Curt had no say in the matter. He promised that he would never experience that feeling of being traded ever again.

There was no such thing as free agency at the time, and once the players signed their initial contract, they had absolutely no control over where they played, which got even worse in the mid 1960’s, when baseball implemented the draft. Once players were drafted, they had no say regarding which team they signed with. Free agency was a foreign word when Curt Flood was coming into the major leagues.

PH His experiences as a minor-leaguer in High Point, North Carolina influenced him to stand and fight when he was then traded in 1969

BS Curt Flood lived through the civil rights movement. When Dr. Martin Luther King was boycotting the bus system of Montgomery, Alabama, Curt was an 18-year-old kid from Oakland who didn’t know what southern-style segregation was. He was sent across the country to play in High Point, North Carolina, where he was one of the first black players ever in the Carolina League. It was a complete cultural shock for him. He lived apart from his teammates — he would go to the bathroom apart from his teammates, he would sleep apart from his teammates, and was completely alienated from his teammates. After about a month of this he wanted to come home, but Bobby Mattick, the major league scout who had signed him, said that he needed to stick it out, that he was not coming home. This experience really radicalized Curt because it opened his eyes to injustice, not only of the system in baseball, but to what was going on in the civil rights movement.

Despite everything he was experiencing in the South, he hit .340 in the Carolina League and was named the league’s player of the year. Following the season in High Point, he went to Savannah, Georgia, where he experienced more Jim Crow. When he got traded following that 1957 season, he experienced the injustices of the reserve clause.

He struggled as a young player with the Cardinals, but even during these struggles he fought to integrate the spring training facilities in St. Petersburg, Florida, where the black players were staying in private homes, apart from their white teammates. For a time he played for a manager, Solly Hemus, whom he and his best friend on the team, Bob Gibson, considered to be racist. Years later, in 1964 — a year in which he played in the World Series — he needed police protection to move into an Alamo, California neighborhood after the realtor who sold him the house had been threatened with a shotgun. This was in a community in which Curt didn’t think discrimination existed. So, these were all very radicalizing experiences for Curt, and he felt very strongly about standing up for himself, and for standing up against injustice, and by the time he was traded from the Cardinals to the Phillies in 1969, he was prepared to speak out.

PH Which is when he consults with the attorney Marvin Miller …

BS Yes. He decided that rather than face the decision of having to either be traded or quit the game, he would sue baseball over the reserve clause. At the suggestion of St. Louis attorney Allan Zerman, they contacted Marvin Miller, who had been executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association for about three years — he was really just getting his feet wet in baseball. They met in New York, where Marvin proceeded to tell Curt every horrible thing that was going to happen to him if he did this, that he wouldn’t ever get another job, that he would be black-balled from the game, that he will never get a job coaching, and that his association with major league baseball will be over forever. He then told Curt that, given the Supreme Court decisions of 1922 and 1953, his lawsuit was a million-to-one shot, and that even if here were to win the case, he would never see a dime because the court would not give him retroactive damages for all the contracts he signed under the reserve clause. But Curt felt that this lawsuit would benefit future players, and that was good enough for him. So, even though he knew he would lose his career over this, the inspiration he got from watching Dr. King, from the events of the civil rights movement, and from everything he experienced both in and out of the game, made him want to do go forward with the lawsuit.

PH Despite what Miller told him, Flood sent a letter to baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn, telling him that he didn’t feel as if he were a piece of property that could be bought and sold

BS Yes, but one very important thing happened first. In December of 1969, Curt went to Puerto Rico to discuss his plans for the lawsuit with the player representatives, who voted 22-0 to support Curt’s plan. They also agreed to pay for his legal counsel. This was a smart move on Marvin’s part because he knew that this lawsuit would affect the future of the Union, so he wanted some sort of control over how it would be managed. Curt and Marvin worked together on that letter to Kuhn, which was basically the emancipation proclamation of the major league baseball players. After Kuhn received the letter from Curt that said he didn’t feel he was a piece a property to be bought and sold irrespective of his wishes, Kuhn wrote back and basically said that it’s too bad, that is the way it has always been.

PH Right, and there is nothing you can do about it. I recently read a piece written in 1888 by John Montgomery Ward, a lawyer, player and one of the founders of the Players League, in which he said that he didn’t want to be treated as chattel. Yet 80 years later, this system remained the status quo

BS It is quite different for John Montgomery Ward, who described himself as “chattel” in 1890 as a white, Columbia-educated lawyer. It is a whole different ball of wax, when Curt Flood, on January 3rd, 1970, is asked by Howard Cosell, “What’s wrong with a guy making $90,000 a year being traded from one team to another? Those aren’t exactly slave wages.” And Curt’s response is, “A well-paid slave is nonetheless a slave.” What this basically did was connect him to the civil rights and black power movements, and turned reactionary white America against Curt Flood.

PH Given the complexities of the era, it is understandable that people would be enflamed by that kind of language.

BS Absolutely. Curt Flood was playing in Richard Nixon’s America, with Phillip Roth satirizing both Nixon and Flood in “Our Gang.” Earl Warren’s Supreme Court was dead and gone at that point, so it is possible he may have had a more receptive Court, or a more receptive America, in 1964 or 1965. But by the end of 1969 and the beginning of 1970, America was tiring of the civil rights movement — they were basically saying that enough was enough, and that is what they said to Curt as well.

PH So Cosell’s comment about Flood’s salary reflected the common man’s view

BS That’s right. The common man’s view at the time was, “I’d play major league baseball for free.” Well, you really wouldn’t — everyone needs to make a living. Curt ushered in a change in baseball, but also a different way in which our society would operate. During the time of Curt’s lawsuit, people wrote for the same newspaper or the same radio station, and worked at the same job for 30 or 40 years. People would only have one or two jobs in their entire lifetime. Curt really ushered in the dawning of free agency for all of us. In A Well-Paid Slave, I quote Loren Steffy of the Houston Chronicle as writing, during the 2005 World Series, “We may not want to admit it, but there’s a little Curt Flood in all of us. If baseball is an analogy for life, then we have become a society of free agents.” People today are always looking out for a better job — why should it be any different in baseball? That is what Curt was saying, but it was a hard concept for people to grasp, especially for a major league baseball player in 1970.

PH You said earlier that the Major League Baseball Players Association voted 22-0 to support Flood. When the case was argued in United States District Court in Manhattan, retired players Jackie Robinson and Hank Greenberg testified on his behalf, but no active players showed up to support him. Why not?

BS Marvin Miller, who was a master strategist, said that he made a big mistake in not encouraging other players to come out and show support for Curt at the trial because it would have been good for them to be seen sitting in the back of the courtroom, even if it was just for an hour. Since players were coming into New York all the time for games with the Mets and Yankees, this would have been possible. But a culture of fear existed among the players at the time — even Bob Gibson, who was Curt’s best friend on the team, said that while he was behind him, he would be 300 paces behind him. Players had very little power, and if they spoke out or even just showed up at Curt’s trial, they could possibly be on a different team the next day, or be out of baseball entirely. Given the lack of free agency and baseball’s monopoly status, there was absolutely nothing a player could do to prevent that from happening.

Besides the fear factor, another reason why players didn’t show their support for Curt during the trial is that the players didn’t really understand the ramifications of Curt’s lawsuit and how it would affect their lives going forward. I think if they had understood the ramifications of the lawsuit, then some of them would have come forward. Joe Torre was a teammate and supporter of Curt’s, and when I interviewed him for the book I asked why he didn’t go to the trial, and all he could say was that he didn’t have a good answer for me. He was as honest as he could possibly be. I think the real reasons he and other players didn’t attend were fear of reprisal, and that they just didn’t understand how important this lawsuit was.

PH Because of the prior Supreme Court decision, you point out that Miller knew that the only place anything would happen is in the Supreme Court itself

BS That’s right. Marvin Miller and Curt’s other attorneys, including Arthur Goldberg and Jay Topkis at Paul, Weiss, were trying to build a legal record to lay a factual foundation for their arguments before the Supreme Court, because they knew when they took the case that the whole ball of wax was going to end up there. So they brought in witnesses like Jackie Robinson, Hank Greenberg, and The Long Season author Jim Brosnan, who would build a foundation about the injustice of the reserve clause.

The other thing they were trying to do was generate public support and sympathy for Curt, and to raise public awareness about the unfairness of the reserve system on major league players — this was a trial on the front pages of the sports section throughout May and June. Jackie Robinson was sort of crippled at this time and used a cane, and when he walked into the courtroom, it was a very dramatic moment. Curt said that when Jackie leaned over and whispered into his ear that he was doing the right thing, and to keep his head up, tears came into his eyes. That moment, when his hero told him he was doing the right thing, elevated the entire ordeal for him. It was also a big moment when former owner Bill Veeck said in the courtroom that, for the good of the game, it was time to usher in some sort of alternative to the reserve clause in fairness to the national pastime. That was huge. Veeck had such a sharp wit, and was one of the great trial witnesses of all time.

PH Curt, on the other hand, was not the best witness …

BS He was a terrible witness. At the time, I think Curt was addicted to two things — alcohol and baseball. Without baseball he went through some sort of withdrawal, and began to lean more heavily on alcohol, which contributed to his running out of money. He owed child support, he had some business reversals, and had not done a good job managing his money.

Curt Flood was public enemy #1 in May and June of 1970. Ninety percent of the sports writers were reactionary and were “buddy-buddy” with the owners, writing that Curt was going to ruin the game of baseball. Curt was getting hate mail that eventually drove him to Denmark, where he stayed following the trial until Washington Senators owner Bob Short coaxed him back into baseball by purchasing his contract from the Phillies in 1970. By this time, Curt had been away from the game for a year — a year spent drinking. He returned completely out of shape, and for a guy who relied on his speed, quickness and hand-eye coordination, his lack of conditioning made his time with the Senators a disaster. I don’t know if he returned because of his desire to play the game or because he needed the $110,000 Short was paying him to play. Bob Gibson told the press the money was the reason Curt returned to baseball. This was really a sad time in Curt’s life, and after three weeks he fled the team and moved to Spain, where he basically exiled himself from this country for the next five or six years. He lived there in a sort of alcoholic haze in Spain while his case was going on.

.

PH When he returned to the Senators, his manager was Ted Williams, who said that Flood can’t play a lick. Flood himself told teammate Elliott Maddox that he had “lost it.”

BS Williams was mad at Bob Short, who was a charlatan-like owner looking for the quick fix. During this time Short traded the entire left side of his infield — he traded third baseman Aurelio Rodriguez and shortstop Eddie Brinkman for the washed-up pitcher Denny McLain — and a few weeks later he acquired Flood, which Williams was not happy about since Short didn’t consult with him about either deal. Since Williams felt Short was making so many dubious decisions, he believed that, in Flood, Short made another bad deal and got another washed-up player, brought in merely to sell tickets. So, while Williams was nice to Curt in the press, privately he had no confidence in him, and Williams was right, Curt could not hack-it anymore. Williams had no confidence in Curt, and benched him three games into the season. Imagine one of the highest paid players on the team being benched three games into the season – it is almost unfathomable that would happen today, yet that is what Williams did to Curt. But this wasn’t Ted Williams’ fault — Curt was done. Williams was trying to put the best men out on the field.

PH You describe the oral arguments of Flood’s attorney Arthur Goldberg as being “disastrous,” yet Goldberg was one of the greatest legal counsels of all time

BS Marvin Miller had worked at the Steelworkers Union when Arthur Goldberg was their general counsel. Goldberg was basically running the Union. Goldberg’s knowledge in labor relations factored heavily in President Kennedy’s decision to name him the Secretary of Labor. So, given Goldberg’s labor relations background and experience on the Supreme Court, Miller thought he would be a natural person to defend Curt. The problem was that two or three months prior to the trial, Goldberg announced his candidacy for governor of New York. He should have said that taking Curt’s case would have been too much for him to do, but he tried to do both, and he did both very badly. He ultimately lost to Nelson Rockefeller in the governor’s race, and he was really ill-prepared for Curt’s trial.

The trial not only exposed how ill-prepared Goldberg was, it also showed that somewhere along the line he lost his litigation skills and his skills as an oral advocate, which was starkly clear in his arguments before the Supreme Court. Goldberg’s associate at the law firm wrote a wonderful brief that helped get the case heard before the Supreme Court, so he may have been overconfident in thinking that that the Court wouldn’t take the case merely to affirm the two prior Court decisions, that they would want to set the law straight. I think Goldberg may have believed he had the case won once the Court agreed to hear it.

People say that a case can’t be won on oral arguments, but it can be lost, and if ever a case was lost at oral argument, this was it. Watching Arthur Goldberg as Curt Flood’s oral advocate was like watching Willie Mays stumble around in the New York Mets outfield in 1973. He was once a great lawyer, but I think this was a case of stage fright arguing in front of his former Court colleagues, and there were signs that he was years removed from being the great oral advocate that he once was. Any third-year law student could have given a better oral presentation and advocacy of Curt’s legal points than Goldberg did that day. It was really sad, and it was sad not only for Arthur Goldberg as a person, but it was especially sad because everything that Curt Flood had fought for and sacrificed went down the drain beginning with Goldberg’s oral argument.

PH The Court had new Richard Nixon-appointed Justices, which may have worked against Curt as well

BS Yes, Earl Warren had stepped down in late 1968, when the Democrats tried to replace him with Abe Fortas, whose nomination failed miserably in the midst of a financial scandal. In a three-year span, Nixon appointed four new Court justices, as well as the new chief justice, Warren Burger. Two of these justices, Lewis Powell and William Rehnquist, came to the Court after it had agreed to hear the case. So the Court had become much more conservative than it was two or three years before, which was working against Curt. However, despite Goldberg’s bad oral argument, and despite Nixon’s packed Supreme Court, he came one vote from winning the case.

PH A conflict of interest played a part in how this case progressed as well

BS That’s right. Besides being a former president of the American Bar Association, Lewis Powell was a very wealthy man who owned a lot of stock in large corporations. In order to avoid any potential conflict of interest, during his nomination procedure he promised the Senate that he would not vote in any case involving companies he owned stock in. So, after Powell sided with Curt and said that the concept of major league baseball not being interstate commerce was ridiculous, and that baseball should be treated like every other professional sport that was subject to anti-trust laws, he recused himself from the case because he owned stock in Annheuser-Busch, the company which owned the St. Louis Cardinals. With that, Curt lost a crucial vote, and the Justices deadlocked four-to-four. Had Powell remained in the case, Curt would have won. Rather than ending up with a four-four tie, which would have left the Court offering no opinion and would have basically affirmed the lower court’s opinion without comment, Chief Justice Burger decided to change his vote at the eleventh hour because his childhood friend, best man at his wedding, and fellow justice Harry Blackmun had written an ode to baseball that Burger reluctantly decided to support. While baseball won on a five-to-three vote, it proved to be a hollow victory. It was an embarrassing opinion by Justice Blackmun, and a really odd situation that a good oral advocate could have turned in Curt’s favor.

PH Blackmun’s list of the 79 great players, and the angst he later felt about it — for example, leaving Mel Ott off the list — was laughable!

BS As embarrassing as that was, the crime was really not Blackmun’s list. In the middle of his opinion on Curt’s case, he wrote an ode to baseball and made this list you referred to, which he became obsessed with. Instead of explaining his legal reasoning to the American people, he became obsessed with getting his list of great ballplayers right — so much so that he was adding players to the list ever after the decision had gone to the printer!

Moe Berg died on June 15 of 1972, and Blackmun decided to insert his name on to the list. Berg was an undistinguished, light hitting catcher whose claim to fame is that he was a World War II spy, and who fans would say of him that he could speak seven languages, but he couldn’t hit in any of them. He was not known for his greatness as a ballplayer, but for his eccentric personality and extreme intelligence. This obsession of Blackman’s shows what often happens in legal cases involving sports — judges lose their legal compass and become sports fans, forgetting about what the law says or what it is supposed to say, and they become pom-pom waving fans.

PH You wrote that, in this case, “Some of the justices seemed to have bowed to the aura and mystique of baseball as the national pastime rather than striving to correct two of the Court’s erroneous decisions. They compounded the errors in those decisions and compromised the Court’s integrity.” They got caught up in the glamour of the game

BS The Supreme Court’s “Flood v. Kuhn” decision is almost indefensible. Very few legal scholars in this country would be willing to defend that decision simply because it is such a strained reading of the Sherman Antitrust Act. It is the kind of decision that someone like Antonin Scalia, a textualist who reads statues based on their plain language, would think is absolutely absurd.

PH Despite the Supreme Court decision, the business of baseball changed forever as a result of Curt Flood’s case. One example is the “Curt Flood Rule,” which was negotiated into the basic agreement between major league baseball players association and management, and meant that players who have been with a team for five consecutive years, and who have also been a major league player for 10 years, can’t be traded without their consent

BS During Curt’s lawsuit, one of the owner’s main arguments was that this was not a legal or antitrust issue, it was a labor relations issue, so they felt it was something that could be negotiated at the bargaining table. The truth is that the owners were never going to get rid of the reserve clause at the negotiating table without a legal defeat or a defeat in front of an arbitrator. But, while Flood’s lawsuit was going on, labor negotiations were also going on because the collective bargaining agreement was about to expire. During the negotiations, Miller basically told the owners that it was time to “put up or shut up,” and to be reasonable at the negotiating table. He ends up negotiating three things three things that changed baseball forever; one, he negotiated grievance arbitration, allowing the players to take their grievance to an independent arbitrator rather than the commissioner; two, if the players had a salary dispute with the owner they would be eligible for salary arbitration; and the third thing is the “10-and-5 Rule”- originally referred to as “the Curt Flood Rule” — which, as you point out, said that if a player had ten years of major league service time and five years with the same team, he could not be traded without his consent. If the “10-and-5 Rule” had been in effect when Curt was traded from the Cardinals to the Phillies, he could have refused that trade. These three things turned out to be huge for major league baseball, because we still have salary arbitration today, the “10-and-5 Rule” is still in existence, and grievance arbitration was the mechanism the players used to gain free agency.

PH So Flood’s lawsuit was not only not in vain — as it turned out, it changed baseball.

BS Absolutely. Curt Flood’s lawsuit didn’t level the playing field, but instead of it being on a 90-degree tilt, it was more like on a 70-degree tilt. It changed public opinion, it raised public awareness that professional athletes were working under an unfair economic system, and it really accelerated the process in which players achieved free agency. While I can’t prove that, if you look at all the incremental gains they made at the negotiating table while Flood’s lawsuit was going on, you have to acknowledge and recognize that those gains were caused by Curt’s lawsuit.

PH For a long time following the lawsuit, Curt Flood himself did not do well. He was an alcoholic and had a variety of troubles. When he returned to the United States from Europe, I recall his brief career as a color announcer for the Oakland A’s, a time that was star-crossed from the very beginning because of his personal problems. In later years he was able to reconnect with baseball, and did a little better, but this is not a story with a feel-good-ending as far as Curt Flood is concerned.

BS Yes and no. One of the casualties of Curt’s lawsuit is that his relationship with the love of his live, Judy Pace, ended, but they then reunited in the mid 1980s. Curt sobered up and they get married, giving him a second chance at marriage and at fatherhood, helping to raise Judy’s two daughters. I believe the last ten-to-fifteen years of Curt’s life were happy ones, but, despite the recognition Curt got for what he did, he was still really on the outside looking in. Marvin Miller’s prophecy about Curt being black-balled from the game stayed true until the end — he was never able to get that elusive job in baseball he always wanted. So, yes, since he was never fully accepted back into the fold, there is a bit of sadness there. And, while he was never destitute, he didn’t really have any money. What he had instead was spiritual. In 1980, when he was still going through a rough period, he told the Oakland Tribune, “What about freedom makes us march and picket and sometimes die? It is the right to choose. To me, freedom means simply I belong to me.” That encapsulates what Curt’s entire lawsuit was about — the sense that no one was the boss of Curt Flood, that he was his own man in many respects. Curt was not a loud-mouth radical in any way — he was a very soft-spoken, very intelligent, very artistic, multi-talented individual, but he had a really great sense of right and wrong, and he was very principled. It was those aspects of his personality that caused him to do what he did.

PH You said earlier that Jackie Robinson was his idol and a key role model

BS Yes, Robinson had tremendous influence on Curt Flood. If there is a guardian angel in this book, it is Jackie Robinson. Jackie broke into major league baseball in 1947, when Curt was nine years old, so Curt idolized him. When Curt was having trouble in the minor leagues, he kept playing because of Robinson’s inspiration. He also got to play against Robinson in one of the last games of Jackie’s career, which was one of the first games of Curt’s career. Robinson is the one who got him involved in civil rights activities when he invited Curt to speak at an NAACP rally in Jackson, Mississippi. And, when no one else would, it was Robinson who testified for Curt at his trial in 1970.

There is a link between Jackie Robinson and Curt Flood, because what Robinson brought was racial equality and racial fairness to major league baseball, and what Curt brought was some economic justice — he was the next generation’s Jackie Robinson. Jackie Robinson started a racial revolution by putting on a baseball uniform. Curt Flood started an economic revolution by taking his uniform off.

.

___________

.

.

“I lost money, coaching jobs, a shot at the Hall of Fame. But when you weigh that against all the things that are really and truly important, things that are deep inside you, then I think I’ve succeeded. People try to make a Greek tragedy of my life, and they can’t do it. I’m too happy. Remember when I told you about the American dream? That if you worked hard enough and tried hard enough and kicked yourself in the butt, you’d succeed? Well, I think I did, I think I did.“

– Curt Flood

.

*

.

.

.

.

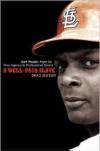

A Well Paid Slave:

Curt Flood’s Fight for Free Agency in Professional Sports

by

Brad Snyder

.

*

.

.

About Brad Snyder

Brad Snyders writing has appeared in numerous publications, including The Baltimore Sun, The Washington Post, and the St. Petersburg Times. His previous book, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators, won the Robert Peterson Recognition Award from the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) and was a finalist for SABRs Seymour Medal, Spitball Magazines Casey Award, and Elysian Fields Quarterlys Dave Moore Award. He is a graduate of Duke University and Yale Law School.

.

.

*

.

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Neil Lanctot, author of Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution.

__________

.

.

This interview took place on February 25, 2008

.

.

# Text from publisher.

.

.

.