.

.

.

.

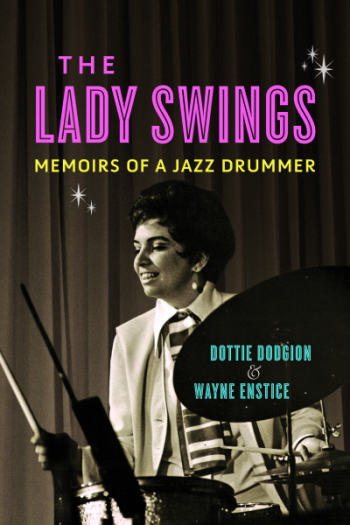

…..On September 17, 2021, the accomplished jazz drummer and vocalist Dottie Dodgion died in Pacific Grove, California at the age of 91. Shortly before her passing, her autobiography, The Lady Swings: Memoirs of a Jazz Drummer (written with Wayne Enstice) was published by the University of Illinois Press.

…..An entertaining read and an important contribution to jazz music’s history – particularly in the way she sheds ample light on the challenges women faced in performing in a mostly-male world – her life story is one of early hardship and opportunity, and includes colorful tales featuring many of the biggest names in jazz. (I will soon be publishing an interview with Mr. Enstice).

…..In this chapter titled “Mingus,” Ms. Dodgion describes her experiences singing in late-1940s jam sessions and night club performances with the legendary bassist Charles Mingus.

.

.

___

.

.

“When I first caught Dottie Dodgion in action I was bowled over. I didn’t hear a great female drummer but a truly great jazz drummer, period, able, as you’ll be happy to learn from the story she tells with such insight, humor, and complete honesty, to please both Charles Mingus and Wild Bill Davison. The lady’s words swing as hard as her ride cymbal, and will keep your foot tapping all the way through.”

-Dan Morgenstern, Director Emeritus, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University

.

.

Photo by Julie S. Ahearn

Dottie Dodgion was a trailblazing American jazz drummer

.

.

Wayne Enstice is a coauthor of Jazzwomen: Conversations with Twenty-One Musicians and Jazz Spoken Here: Conversations with Twenty-Two Musicians

.

.

.

Excerpted from The Lady Swings: Memoirs of a Jazz Drummer by Dottie Dodgion and Wayne Enstice. Copyright 2021 by Dottie Dodgion and Wayne Enstice. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

.

.

___

.

.

…..I was with Nick Esposito from 1945 until 1949, but we weren’t working all the time so I took jobs with other bands whenever I could. One of those jobs was an eye-opener.

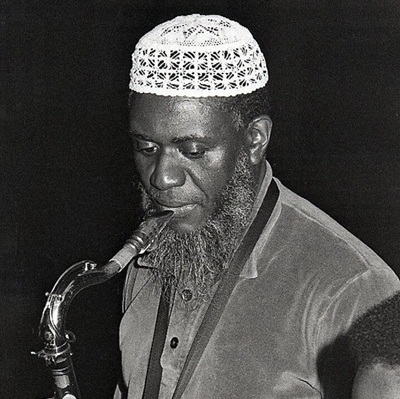

…..In 1947, I went to hear a jam session in an Oakland club featuring a new jazz-world sensation, bassist Charles Mingus. Mingus had temporarily settled in the Bay Area with an ambition to break the color line of the San Francisco Symphony, to be the first Black musician accepted into that conservative institution. He was a genius on his instrument but the symphony people didn’t care—they wouldn’t let him in. When I got to know Charles better I heard him describe that incident with one-word: bigotry.

…..That evening at the jam I was so completely lost in the music that my recognition of racial politics, along with any other markers of my immediate reality, faded away. I was so absorbed that it startled me when late in the set someone on the stand yelled, “Hey, Dottie, come up and sing!” I left my seat with the jitters—I mean, singing impromptu with a musician of Mingus’s caliber was daunting—but it didn’t stop me. As my father had told me years before: “That’s not the time to fold. It’s the time to pour it on!”

…..Jamming with Charles that night it was obvious that our time agreed. I figured that maybe the way we hit wasn’t lost on him either and that maybe he filed it for future reference. And maybe he did, because the second time was the charm. In 1948, I rejoined Nick Esposito at Facks and a few nights after we opened, Mingus came into the club. He nodded, I smiled, and the band kicked off one of my wordless features.

…..Hearing me do phonetics with Nick was probably as unexpected for him as it was fortuitous for me. At the close of the evening an intrigued Charles asked me to a rehearsal, and after we met up a few days later he expressed his confidence that I could handle the vocal parts he was experimenting with in his band. In fact, Charles never doubted me at all, even though I couldn’t read. Charles was always inventing and soon I was to become one of his inventions.

…..When I started with Charles he had Buzz Wheeler on piano and Kenny McDonald at the drums. The guys were deep in rehearsal even though there wasn’t a gig on the horizon. I guess, since he was in the Bay Area by himself with nothing else to do but wait on a decision by the city symphony, why not rehearse? Rehearsals continued for several months after I joined, and they made a lasting impression on me because we worked five hours a day, three days a week. Charles was a perfectionist and it was clear to all of us at the rehearsals that whenever we did get to play on a gig, there wouldn’t be any second chances to correct mistakes; we had to get it right the first time. If you didn’t want to practice for five hours you were out of the band.

…..Mingus could be a sweet huggable bear one moment and very intimidating the next. You arrived and there was no small talk. He wasn’t interested in our personal lives; he wasn’t rude, but there was no doubt that Charles, at twenty-six years old, was the Big Daddy. He treated all us young kids like beginners at a lesson every time we played with him. He told us what to do, what and when to play—he had everything figured out. You had to pay close attention or he wouldn’t have any use for you.

…..Similar to what I did with Nick, I performed like a horn in Charles’s band. I had specific notes to sing in both bands and I sang them within the chords exactly. I never sang words with either of them. Instead, I vocalized the set melodies using the sounds of vowels and consonants. The difference between the two bands was that with Nick it didn’t matter which vowels and consonants I used, but it did with Charles. Sometimes he’d want me to sing B’s, sometimes he’d want D’s. I sang an instrumental part in both bands, but I did that with Charles by repeating a set vowel or consonant sound to blend as he bowed the harmony on his bass. Charles didn’t use the term phonetics to describe what I did with him; it was closer I think to vocalise, which may be defined as using the same vowel or consonant to sing the exact notes on a chart every time a tune is played. (Vocalise is distinct from vocalese as practiced by, for example, King Pleasure, Eddie Jefferson, or Jon Hendricks, where lyrics are added to preexisting instrumental jazz solos.)

…..Since Charles knew I couldn’t read, he didn’t write out parts for me. Once again, I did it by ear, memorizing the music as we rehearsed it over and over, so by the time the rest of the guys got it, I had it down, too. The one tune I definitely remember doing with Charles was an arrangement he wrote on a popular song, “The Gypsy.” I was thrilled to do that tune, given its jazz pedigree: it had been performed the year before by Charlie Parker during his so-called “Lover Man” date for Dial Records. All that work paid off when Charles’s bowing parts and my vocalise finally meshed and a grin appeared on his face. I loved seeing that great big grin!

…..Around Christmas, 1948, Charles landed an extended gig at the Knotty Pine, a biker bar on 18th and San Pablo in Oakland. I remember this because it was at the same time that a nearly year-long recording ban, enforced by the American Federation of Musicians, was lifted. Even with the gig, we continued to rehearse several days a week and our band was hot, it was together, and as word got around I was proud to be a part of it. My dear friend, Dee Marabuto, whose husband, John, was in Nick Esposito’s band with me, heard us at the Knotty Pine, and she remembers that “it was the talk of the town within the musicians’ circle that Dottie was going to be with Mingus.”

…..We played New Year’s Eve at the Knotty Pine and, as the evening wore on, Charles got more and more exasperated with his drummer, Kenny McDonald. McDonald kept messing with the time and Charles kept warning him, “If you don’t quit looking at the bitches and concentrate I’m going to throw you off the stand!” Well, later in the set, that’s just what he did! We were on a high stage and Charles took McDonald by his lapels and threw him clean off! McDonald plummeted down a flight of stairs behind the drum chair and—God!—I thought Charles had killed him! (McDonald survived but Charles had to scramble to replace him, finally hiring Johnny Berger.)

…..Mingus disbanded our group after the Knotty Pine gig and left the Bay Area. I didn’t see him again until maybe fifteen years later when he came into the famous Half Note jazz club on Hudson Street in New York City where I was playing with Zoot Sims. When Charles spied me on the stand he stared quizzically; up to then he’d had no clue that I played the drums. He made his way over to the stand and shouted at me while we were playing: “Dottie, is that you?” I yelled back, “yeah,” and Charles told Zoot, “I want some!” Charles sat in and it was fun as hell; all the while we played he shook his head and repeated, “Damn, Dottie, Damn!” That was cute.

…..After Charles left town early in the new year, 1949, I was back with Nick Esposito’s house band at Facks. Shortly after my return, jazz piano giant, Art Tatum, played opposite us for a week. During Tatum’s sets everybody in the house was absolutely mesmerized; this was late in Tatum’s career, but he was still untouchable at the keyboard. Once he’d finish a set everybody wanted a piece of this blind genius.

…..Except me. I listened closely to the music, but when it was done I was very good at stepping back to leave the man alone. I wasn’t fascinated by fame. My daughter, Deborah, once said to me, “Oh, you’re afraid of becoming famous.” I said, “Yeah, you’re damn right, I don’t want to be a household name.” Those people don’t have a life of their own and they don’t know who loves them. I like incognito. I want to be cool, but underneath; I want to come from underneath and have the fun, which I did.

…..A few weeks after Tatum left, tenor saxophonist Charlie Ventura brought a combo to play opposite us at Facks, and the music was right in my bag. Ventura, who had gained fame as a soloist in Gene Krupa’s band, led a bop septet that included the relatively new vocal duo of Jackie Cain and Roy Kral. I hadn’t heard of Jackie and Roy, but the first time Jackie sang at the club I was in awe—on some numbers she was doing phonetics and that was the first time I ever heard anyone else do it.

…..The more I listened and learned about Jackie and Roy the more I felt that, next to them, I was back in junior high. Before their appearance opposite us, they had made a series of recordings with Ventura and played L.A. They were getting bigger and bigger and bigger. When Esposito’s band took the stand, Jackie and Roy heard me sing in that same new style, but since we never traded stories I don’t know who got there first. What I do know is that I didn’t copy Jackie Cain. I sang wordless melodies before I knew she existed. In May 1949, an unexpected gift fell in my lap. I entered a recording studio for the first time and waxed two sides with the Nick Esposito Boptette, an expanded group that included Nick on guitar; plus tenor saxophonist, Claude Gilroy; pianist, Buddy Motsinger; Vernon Alley at the bass; Joe Dodge behind the drums (a few years later, Dodge was part of an early edition of the Dave Brubeck Quartet); and Cal Tjader on bongos. Tjader had played in Brubeck’s octet three years before this date. As Dottie Grae, I sang phonetics on two tunes: “Dot’s Bop” (written especially for me by Nick Esposito and pianist/composer Dick Vartanian), and “Penny,” by Shelton Smith. band also cut two instrumental numbers. All four selections were in San Francisco and released by 4-Star records.

…..Not long after the recording date, I left Nick’s band, at least temporarily. I can’t remember if work had dried up or if I got restless for something new. In any case, I was at loose ends so I went down to Los Angeles and stayed with my paternal grandparents in Hollywood while I looked for work. I was surprised to learn that my name had gotten around among L.A. musicians. Known as a pretty good singer who was reliable, stayed in tune, knew her keys and her tempos, I was hired for different local gigs—a Saturday night here, a weekend there—and was introduced to the “Grandfather of Film Music,” David Raksin.

…..Raskin took a liking to me and circulated my name among various agents. His recommendation carried weight; I was hired a little bit more, and I sat in some, too. Pretty soon I was appearing regularly on the streets in Hollywood. I started running with the L.A. crowd and hanging out at Billy Berg’s on Vine. That’s where I first heard Anita O’Day. Her time was so great; oh, God!—her vocals were like tap dancing to me.

…..I was in my element in Hollywood, surrounded by a jazz scene filled with new faces and sounds. Somewhere in that excitement, someone told me that the comedian, Roscoe Ates, was looking for a singer who could feed him straight lines to take on the road. I decided to audition. Another shot at touring was too good to miss!

.

.

___

.

.

Excerpted from The Lady Swings: Memoirs of a Jazz Drummer by Dottie Dodgion and Wayne Enstice. Copyright 2021 by Dottie Dodgion and Wayne Enstice. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

.

.

In this mid-2010’s video, Ms. Dodgion tells a classic Benny Goodman story, and performs “Deed I Do” with her trio

.

.

.