.

.

.

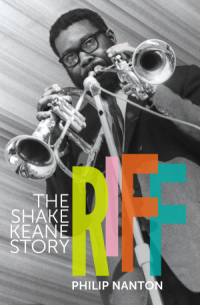

…..Shake Keane was the star sideman in the ground-breaking Joe Harriott Quintet of the 1960s. A jazz virtuoso on trumpet and flugelhorn, he was also an original and award-winning poet. What went into the making of this shapeshifter from the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent? In Riff: The Shake Keane Story, author Philip Nanton explores a turbulent life.

.

.

“The story of Shake Keane has never been more inspiring or relevant to the times in which we live. Born in St Vincent, the trumpeter was an integral part of innovative bands led by Joe Harriott and Michael Garrick in the 1960s, and defied expectations of what a West Indian musician could achieve in post-war Britain. Keane was also an accomplished poet with a sharp wit and strident humour. Philip Nanton’s excellent biography creates an engaging portrait of a restless, complex soul.”

-Kevin Le Gendre

.

“This beautiful, evocative biography of Shake Keane explores with equal passion Keane’s double life as poet and musician and his innovation as a virtuoso in both art forms. Nanton brilliantly contextualises Keane’s life through the multiple lenses of Caribbean nationalism, post-war migration and the formation of Caribbean literary identity. A compelling and captivating read.”

-Hannah Lowe

.

“Riff charts the experiences of a gifted, learned Caribbean man who travels to London and cuts his teeth on the jazz scene of the 1950s and 1960s. Nanton’s book connects the brilliant musicians and poets of a thriving creative arts scene while navigating the triumphs and periodic lows of a great personality, poet and trumpet original.”

-Julian Joseph

.

“Philip Nanton has drawn a unique 20th century artist out of the shadows, and in the process established Shake Keane on the podium of Caribbean originals that’s been awaiting his arrival for decades.”

-John Fordham, London Jazz News

..

.

In this excerpt from the book’s first chapter – published with the gracious consent of Papillote Press – Nanton writes about his initial meetings with the celebrated artist, and the 20th century currents that were important in shaping his individual talents and personality.

.

.

photo by Mario Porchetta

Philip Nanton is a writer, broadcaster, poet and performer. Born in St. Vincent, he now lives in Barbados. His books, Island Voices for St. Christopher and the Barracudas (2014) and Canouan Suite and Other Pieces (2016), mix poetry and prose, and art, and were both published by Papillote Press. His latest book, Frontiers of the Caribbean (2017) was published by Manchester University Press.

.

.

From Riff: The Shake Keane Story by Philip Nanton. Published by Papillote Press. All rights reserved.

.

.

…..Shake Keane was back home in St Vincent working as a teacher when I first met him in 1979. In his lunch hour, we would occasionally retreat to the quiet of Vee’s Snackette, a tiny bar on the corner of busy Bay and James Street in the island’s capital, Kingstown. The bar, surrounded by shops and government offices, was close to the school where Shake was then teaching. (The entire corner block is now a bright but ugly KFC franchise.) Vee’s had only two windows, one looking out onto each congested street. Smaller than a one-car garage, the bar was a simple room with a garish melamine-coated counter and three high wooden stools. We were the only customers. Miss Vee, a sturdy, no-nonsense lady, would put out a petit-quart bottle of rum and a small bowl of ice for me. Shake’s lunch comprised three bottles of Guinness. She would then leave us alone as she scurried around in a back room.

…..We exchanged returnee gossip about life in England of the 1960s and the effect of coming back to St Vincent. By this time Shake was sceptical about his return. He had abandoned his flourishing jazz career in Europe and lost out to political manoeuvring in St Vincent over the post he had most wanted and had returned to implement — Director of Culture for St Vincent and the Grenadines. Sacked from this job after two years and with no other source of income, he felt compelled to accept the first vacant post and became Principal of Bishop’s College, a grand name for a small secondary school in Georgetown, the island’s second town in the northern Windward district. It seems that even in the relative tranquillity of teaching disaster lurked. At one of our meetings he described almost losing his life when one evening, during his time as Principal, he went to turn on an electric lamp and was hurled across his office. Faulty wiring.

…..Shake was by then in his early fifties; tall and broad, around six foot four and somewhat shaggy in appearance. His size was emphasised by his characteristic loose-fitting clothing above brown latticed leather sandals. By this time he had a luxuriant grey beard and a thinning head of hair. He moved slowly when the pain of gout struck. A large pair of spectacles rested on his nose below heavy grey eyebrows. Between his long delicate fingers he invariably held a roll-up cigarette. He spoke in a deep baritone voice. This apparently fierce demeanour was softened in conversation by an unassuming smile that came quick and easily.

…..Vee’s Snackette looked directly onto the street. Passersby would see him there and hail the famous musician and returned fellow Vincentian. A celebrated figure in the island, he was used to this public show of interest and would often be stopped in the street. A brief chat was a public sign of connection to a man of international stardom. One lunchtime, a young stevedore, hot and sweaty from the nearby docks, entered the bar:

…..‘Mista Car-heen! Mista Car-heen! ’Cuse me sar. Ah have one sar. Don’t mind the clothes all ragga, sar. I just off the jetty. You could hear me sar? Dis one goin be good sar. It go so…

…..I was liming on the block

…..wid de boys from de rum shop

…..is then I bounce up big Mary

…..them days she frennin Big Nancy’

…..‘OK, OK, pal, enough.’

…..‘It have plenty more verses sar. You like how it going? You could help me fix it up sweet, sweet? Put a lil chorus. Get recording contract and ting…. Or even… a lil drink, den sar? Me troat dry.’

…..Shake bought him the drink.

…..Supplicants came in other forms. At one of our meetings I myself showed up with a poem that I’d written. Without hesitation he took out a pen and began deleting words and rearranging its lines, circling sections with arrows going first in one direction then another to different parts of the page, instinctively aiming at bringing the page alive. I like to think I learned something about poetry firsthand from Shake.

…..At this stage of his life he had been back in St Vincent for six years, after more than 21 years away, first in London then in Germany. Other locations, especially New York and Norway, were to follow. These movements suggest an itinerant — a wanderer who was both framed and influenced by the twentieth century, his lifespan stretching from 1927 to 1997. Indeed, he absorbed and was absorbed by many of the currents flowing through the century. In his chosen fields, especially jazz and poetry, he not only understood them but knew how to excel in them.

…..Three twentieth-century currents were important in shaping his individual talents and personality. The first of these was the rise of nationalism in the Caribbean. Shake grew up and lived through a time when regional and island national sentiments were at their strongest — expressed in demands for self-government, the rise and fall of regional federation and, finally, the achievement of island-based political independence. This nationalist current was also flowing around the world, touching the colonies from the Caribbean to Africa and Asia. It brought with it political change and a sense of the importance of nation-making which no thinker of the twentieth-century Caribbean could ignore. But when Shake departed St Vincent for England in 1952, the island was still a colonial outpost; only one year earlier it had experienced its first general election under adult suffrage. When he returned in 1973, it was a few years after the island had attained Associated Statehood with Britain (1969). This was, in effect, when locally elected politicians gained control of the island’s resources and budget, taking over from the British. Six years after his return, St Vincent gained full political independence. If, as a young man, Shake had left a colony, he returned to a place in which local people vied for influence and power and local party politics was ruthless. He returned, therefore, to a different island from the one he had left.

…..The second great current in which Shake was caught up was the experience of migration. The question facing all migrants of ‘where is home?’ becomes especially urgent for a doubly displaced person. As someone who spent the first 25 years of his life in St Vincent, Shake was born into one diaspora. He then lived in England and in Europe for 21 years as a member of another; he returned to his birthplace for eight years before migrating yet again to live the last 16 years of his life in New York. His return to St Vincent captures a common dilemma experienced by many migrants — the desire to offer service ‘back home’ versus self-fulfilment in the adopted country. When such an itinerant is a sensitive professional musician for whom travel to different venues and countries is almost a daily constant, the question of home and homecoming has even more resonance. Not surprisingly, home and the challenges of migration are important themes in his poetry. His early writing begins by celebrating place before becoming, later, a poetry of displacement, playing with multiple positions in relation to the conundrum of home. In tracing this second contextual current we shall see how Shake’s physical movements and creative responses constitute a form of mapping.

…..The third current that shaped his identity was masculinity. By masculinity I do not mean a fixed and limited way of behaving — as though there were only one way to ‘be a man’ — but a range of performances, as man, musician, teacher and poet, through which he searched for a role and a sense of self. His masculinity was tested by his failure to realise his full potential in the jazz world of the 1960s, modest recognition for his poetry, and finally a conventional and serial dependence on the women closest to him. Sometimes the performances coalesced and sometimes they contradicted one another. These currents — nationalism, migration and masculinity — are, of course, intimately connected. Taken together, they have a peculiar power in animating Shake Keane’s life.

…..At the same time, his mature performances, especially as musician and poet, are shaped by innovative presentations that are difficult to pin down. In this way he disrupts the clear lines of demarcation between styles and genres that critics often require. Located at the crossroads between jazz and poetry, Shake’s most significant achievement was ultimately a blurring of the boundaries between these two art forms.

.

___

.

From Riff: The Shake Keane Story by Philip Nanton. Published by Papillote Press. All rights reserved.

.

.

.

___

.

.

Angel Horn

When I was born

My father gave to me

an angelhorn

With wings of melody.

That angel placed her lips

upon my finger-tips

and I became, became

her secret name.

Her name grew strong,

spread like a passion tree.

She named the song,

I played the melody.

And in the morning hour

I awoke to dream of her,

And all day long, day long

I lived her song.

In boat and barge

where songs and seas are friends

our dreams grew large,

made love where dreaming ends.

And people placed her lips

upon our finger-tips,

and friends became, became

our secret name.

Now light is low,

new angels come and go. The passion tree

Spreads dense as destiny.

And this old angelhorn

strives like the lifting dawn!

Love moves to claim,

to claim our secret name.

.

by Shake Keane, From Collected Poems, 181-182

.

.

___

.

.

Listen to a 1961 recording of the Shake Keane Quintet play “How You Say,” with Keane on trumpet, Joe Harriott (alto saxophone); Coleridge Goode (bass); Tommy Jones (drums); and Pat Smythe (piano)

.

.

.