.

.

.

.

…..Sure, Queen’s Gambit, The Crown, and Fargo are pretty compelling programs to watch while under quarantine, but have you seen Young Man With a Horn? How about The Connection? Syncopation, maybe?

…..No, these are not contemporary Netflix productions, they are examples of the more than 100 movies produced since the late 1920s that are stories about jazz.

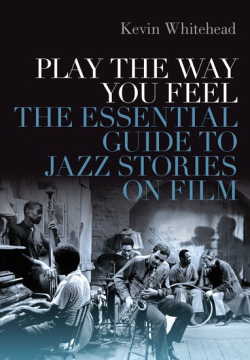

…..I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Kevin Whitehead, author of Play the Way You Feel: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories On Film, an entertaining and comprehensive tour of early talkies, jazz origin stories, biopics, comedies, spectacles and low-budget quickies and musicals. It is a fascinating, rich subject for fans not only of jazz, but also of film.

…..Our interview will be published a little later this month. Meanwhile, with the consent of Kevin and his publisher, Oxford University Press, what follows is an excerpt from the book in which he discusses The Jazz Singer starring Al Jolson, famous for bringing synchronized dialogue to feature films, and also for it being, he writes, “a template for a half dozen jazz stories to come.”

.

.

___

.

.

“What makes all of this quite enjoyable is the colorful way that [Whitehead] writes, his wit, and a countless number of fascinating details… Even the most devoted jazz film experts will learn a great deal from this book.”

-Scott Yanow, L.A. Jazz Scene

.

“Jazz and cinema, the two definitive art forms of the 20th Century, have led an often troubled co-existence. Play the Way You Feel traces the frequent missteps and occasional triumphs of jazz in film with the deep knowledge, superior taste, and acerbic wit we have come to expect from Kevin Whitehead. ÂAn essential book for all jazz fans, and a necessary corrective for anyone whose knowledge of the music is based on what they have learned at the movies.”

– Bob Blumenthal, author of Jazz: An Introduction to the History and Legends Behind America’s Music

.

“Readers… will be rewarded by insights from an author of discerning taste with a deep understanding of his subject, who yields fresh perspectives on even well-known films.”

– Library Journal

.

.

photo by Francesca Patella

Kevin Whitehead, the longtime jazz critic for NPR’s “Fresh Air,” has

written about jazz, movies and popular culture for 40 years. His books

include New Dutch Swing (1998), and Why Jazz? A Concise Guide (2011). His essays have appeared in such collections as Discover Jazz,

The Cartoon Music Book and Traveling the Spaceways: Sun Ra, the

Astro-Black and Other Solar Myths. Whitehead has taught at the

University of Kansas, Towson University, and Goucher College.

.

.

___

.

.

From PLAY THE WAY YOU FEEL: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film. Copyright © 2020 by Oxford University Press and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

.

.

The Jazz Singer (1927; 88 minutes; director: Alan Crosland; story: AlfredCohn, from a play by Samson Raphaelson). Cast includes: Al Jolson (Jakie Rabinowitz/Jack Robin), Warner Oland (Cantor Rabinowitz), Eugenie Besserer (Sara Rabinowitz), May McAvoy (Mary Dale).

—Jakie Rabinowitz pursues a career as blackface entertainer Jack Robin, to the horror of his cantor father. Jack must choose between family and show business when he’s asked to substitute for his dying father at temple, the night of his own Broadway debut.

.

It’s a critical commonplace that entertainment dynamo Al Jolson—a son of Jewish immigrants who was noted for showily emoting as he sang, and who came to prominence performing in blackface, was no jazz singer, despite the title of the Jolson vehicle that brought synchronized dialogue to feature films. And yet The Jazz Singer, about a politely rebellious son whose appetite for modern music clashes with Dad’s conservative tastes, is a template for a half dozen jazz stories to come: stories that will ring changes on its familiar plot, the way jazz musicians make up their own melodies to the chords of George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm.” The Jazz Singer also points the way for other jazz films as the original backstage musical, broadly defined: a story in which the characters are performers who have reasons to break into song—on stage, in rehearsal, sight-reading— and where a performed song’s lyric may (often by happenstance) reflect a singer’s own emotions. Jolson’s Jack Robin sings “Mother of Mine, I Still Have You” on stage, as scheduled, after a surprise visit from mom.

…..The fact that Jolson was ever tagged as a jazz artist reminds us that in the 1920s, when jazz exploded into American culture, folks who invoked the word weren’t always sure what it meant. Was its defining feature improvisation? Syncopation? Was it modern pop, orchestral ragtime, deliberate noisemaking, or stunt work, with drummers bouncing sticks off the floor?

…..Jolson’s conversational emotionalism didn’t have the loose, compelling rhythmic momentum jazz folk call “swing,” but it wasn’t totally unrelated. Famous for rarely singing a song the same way twice, Jolson would alter the melody, phrasing, or lyrics. His half-sung, half-talked routines suggest the influence of one early swinging vocalist, black music- hall comedian Bert Williams, whose line readings jump ahead of or lag behind a written melody with quasi-improvised snap. ( Jolson covered Williams specialties “Nobody” and “Why Adam Sinned.”) But context matters. Jolson didn’t record or associate with players now regarded as jazz musicians (overlooking Cab Calloway’s appearances in Jolie’s 1936 The Singing Kid).

…..We might think of Jolson, stylistically, as a music-hall performer who’d transitioned halfway to jazz, making him the right star for a technologically transitional part-sound, part- silent film that’s about being caught between worlds: between tradition and innovation in music, between religion and the secular life, between the shtetl ways of the hero’s parents and his own let’s-try-anything attitude, between Jewish family and shiksa girlfriend, between dual identities as the Lower East Side’s Jakie Rabinowitz and Broadway’s Jack Robin. Of his progressive views, he tells his parents: “If you were born here you’d feel the same as I do.”

…..He’s also adrift between black and white visages. Late in the film, the first time he puts on blackface makeup—something Jolson’s quick and sure application of burnt cork makes clear he’s done many, many times—Jakie looks in the mirror and sees his cantor-father’s face. Jack’s/Jolson’s blackface routines show how a mask can embolden a performer; paradoxically, it makes him more nakedly emotive. As Ted Gioia has noted, Jolson’s blackface is divorced from shuck-and-jive racial caricature: “He truly had little knack for the ridicule, irony and sarcasm that racist humor requires for its effect.”

…..In The Jazz Singer blackface is one marker of how far Jack has traveled from Eldridge Street. In the most expressive silent scene, he has just blacked up for his Broadway dress rehearsal when his mother comes by his dressing room to talk. She looks at his painted face with utter incomprehension. The gap between their life experiences has grown too great.

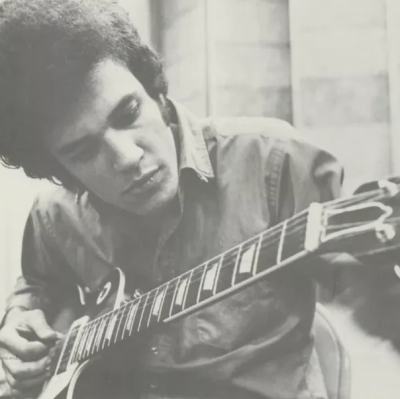

…..Little as it’s noted, The Jazz Singer does in fact boast one of the movies’ earliest jazz solos and some (verbal) improvising. Besides singing and dancing, Jolson did an astonishing whistling bit, demonstrated on “Toot Toot Tootsie,” a virtuoso set piece. Using fingers to help manipulate the airstream, he trills and rips like a bird, with piercing tone, and throws in slippery glissandi all his own, even as he paraphrases the melody and chooses pitches that follow the chords. It’s a routine, but a real jazz solo just the same.

…..The verbal improvising comes later. Years after fleeing home to make his way in the world, Jakie returns to New York to rehearse for a Broadway revue and stops by his parents’ flat where he finds his mother. (She’s played by Eugenie Besserer, a virtuoso of reaction shots after making hundreds of silents.) Jakie leads her to the parlor where—as we switch from silence to sound—he previews one of his featured numbers from the show, Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies.” Jolson inexpertly mimes the piano part; he strides across the keyboard with his right hand instead of his left.

…..He sings one chorus, then breaks off to ad lib dialogue for the microphone, telling Mama how much he loves her, and how great life’s going to be once he makes it and they move to the Bronx. Besserer makes a feeble attempt to keep up, seemingly as knocked out by his prattling as the movie audience was going to be. Then he returns to an even more frenetic “Blue Skies”—“I’m gonna sing it jazzy,” he says, throwing in a few scatlike do-do-dos—brought to an abrupt end when his father appears in the doorway, and yells “Stop!” to end the sound sequence. The cantor’s command to halt progress turns back the clock: it returns us to the silent era, depriving the son of his voice. In that moment the film’s form and content become one.

…..The Jazz Singer anticipates later jazz films in another way, by promoting the notion that for a performance to be valid, the artist has to really mean it—has to sing the way he feels with no faking. At the climax, when Jack debates blowing off his Broadway debut to sub for his dying father at temple on Yom Kippur, Mama advises, “Do what is in your heart, Jakie. If you sing and God is not in your voice—your father will know.”

.

___

.

From PLAY THE WAY YOU FEEL: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film. Copyright © 2020 by Oxford University Press and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

.

.

.

Al Jolson in the famous whistling bit from The Jazz Singer

.

.

.