.

.

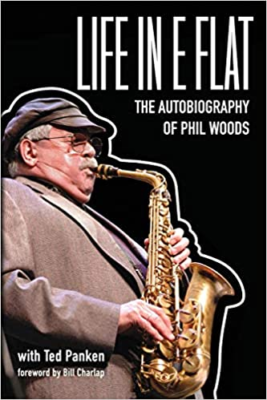

Life In E Flat: The Autobiography of Phil Woods

with Ted Panken

(foreward by Bill Charlap)

.

.

In advance of a soon-to-be-published conversation Jerry Jazz Musician contributing writer Bob Hecht recently had with pianist Bill Charlap and jazz writer Ted Panken about the great saxophonist Phil Woods, the following excerpt from the just released Life In E Flat: The Autobiography of Phil Woods (written with Panken) recalls Woods’ post-high school life as a budding musician from Springfield, Massachusetts, his early memories of work in local jazz clubs, trips to New York to take lessons with the pianist Lennie Tristano, and being introduced to none other than Charlie Parker.

.

.

.

Excerpted from Life in E Flat – The Autobiography of Phil Woods. © 2020 Jill Goodwin. All rights reserved. Published by Cymbal Press, Torrance, CA USA cymbalpress.com. Excerpt published by permission of Cymbal Press.

.

.

___

.

.

I always tell my students that if they have a choice between becoming a musician or a brain surgeon, they should become doctors. Music is for people who have no other choices.

…..I was lucky. I had no choice. After studying Benny Carter, hearing Bird and Dizzy, and then seeing Johnny Hodges I was hooked for life, a bebop junkie. I still am.

…..Hal Serra [his pianist friend] got me a real gig with a real orchestra, a dance at the YMCA with guys from the Westover Air Field band. I played lead alto along with two tenors and a baritone sax. An elderly lady told me that I sounded good, adding, “When you get older, you’ll get a bigger sax.” We also played at the local USO. My folks came to opening night, but they didn’t see me because the music stand was taller than me, so they went home. Next time they showed, I stood on tiptoe to play my solo on “Harlem Nocturne” and all was well. This song would continue to occupy a place in my life like a leitmotif.

…..Once Hal presented me as his kid brother at his gig with Jimmy Brown’s strong swing combo. “I had to take him out,” he said. Hal was into the new bebop thing, and whenever he soloed the guys stared at him disdainfully. They just didn’t get it. The last set wasn’t crowded, so Hal asked Jimmy if “the kid could sit in.” I removed my sax from its powder-blue corduroy case, and took a solo on the blues, playing long lines over Hal’s wild bebop chords. Then you could see a look of comprehension in their eyes. As Hal pointed out, these guys suddenly knew their world had changed.

…..When I finished high school in 1948, Joe Morello got me my first steady six-night-a- week gig at a club called the Blue Grotto with a guitarist named Freddie Dearborn and his wife, May, who played piano. On “Deep Night,” Freddie taught me how to use the low chalumeau register on the clarinet by sticking the bell right into the microphone to get an organ sound that the romancing dancers loved.

…..Sometimes on nights off, we went to the Black section of town, the South End, to the Phono Village, a funky, soulful club that had about 20 round tables designed like record platters, painted with a label and a pin-spot where each light came down. We played there with a vibraphonist named Father Wesley Williams, not that great a musician, but a lovely man. I started going there when I was 14 or 15 to check out another vibraphonist named Prince Buddha, who was world class—the story around town was that he once cut Lionel Hampton in a jam session. The cats there showed me how to play “Coquette” and “Just You, Just Me,” and also “I May Be Wrong (But, I Think You’re Wonderful”), which was the theme song of the famous Apollo Theater, where I later worked.

…..That’s where I had my first reefer, after someone gave some to Hal. I asked, “What’s that?” “Oh, it makes you feel like playing.” I said, “OK, give me some.” Sometimes, to keep going, we broke down Benzedrine inhalers and put them in Coca-Cola.

…..The Phono Village was my real school. I was there every available minute, soaking up that blues feeling and learning tunes. I never felt any draft; the cats were always extremely generous in sharing their considerable musical knowledge. I became enamored with the whole Black experience. The way they talked and walked and looked out for each other. The way they sounded. The humor and camaraderie. They had something I hadn’t seen before, a kind of je ne sais quoi liveliness that was not like the average New England ofay experience—a little more extroverted joy about life. I guess that had to do with the rough road they had to trod to get by, and humor was an important part of it, as was having a music that was really theirs. Even at that point I realized that jazz is essentially a Black invention. The white guys were there to pick up on what the Black cats were doing because of the rhythmical thing and the blue notes. It was apparent to me that this was serious, it was important, and I wanted to learn about it.

…..One night, Gigi Gryce, Horace Silver, and Walter Bolden came down to the Phono Village from Hartford for a cutting contest with our group. They were a set group, with arrangements. Later, they invited Hal and me and Joe to their home base, the Sundown Club in the Black section of Hartford. We didn’t even have a bass player, but we held our own.

…..Joe and I and Chuck Andrus got a gig with Flip Brenner, a pianist from out of state, at a local restaurant/dance hall. The Page Cavanaugh Trio, which did a thing with unison whisper vocals, had a big hit with “All of Me.” We covered the song, whispering the lyric. When the gig ended, Flip arranged an audition in New York for a big-time, cigar- smoking booking agent, whom we dubbed “Zucker, the booker, the New York crooker.” To get the good work in the show bars, bands had to be entertaining—at one point, we all donned football helmets and did a medley of college songs. I had a solo on an old minstrel song called “Sweet Kentucky Babe” that I sang on my knees, using an affected Black accent. It began with the words “Skeeters are a-humming.” Zucker the Booker just stared at us incredulously, and blew cigar smoke our way.

…..That summer, I started going to New York to study with Lennie Tristano, who had been teaching Hal. When Hal showed me what he was learning, I asked if he thought Tristano would take me on. He said, “Sure, he’s always looking for students.” Tristano was doing this for a living then, as an adjunct to his gigs. Every other week, for six weeks, we took the four-hour bus trip to New York, followed by a one-hour subway and bus ride to Lennie’s studio in Queens for a $10 lesson.

…..After the lessons, we rode the subway back to Times Square. We ate spaghetti at Romeo’s (you could tell it was fresh because you saw the pasta in huge steaming vats in the window) or got great pizza on 48th Street just off Seventh Avenue. We were avid DownBeat readers and knew about the latest bebop 78 rpm sides. If we still had some money, we would go to the Main Stem Record Store on Broadway to get the latest shellac by Bird, Bud, Prez, Dizzy, Fats, and whatever else was hot. When we got home, I transcribed the new tunes, just the melodies and chord changes (or heads, as we called them), and put them in my fake books. I memorized the solos that attracted me and played along with the discs. I had a B-flat, an E-flat, and a concert version of every bebop song that came out. We snuck them in on gigs with our newly formed bebop group.

…..If we had still had any money left, we caught a couple of sets on 52nd Street at the Spotlite Club or The Three Deuces or the Onyx. After one lesson Lennie asked us if we were going to 52nd Street. “Sure,” we said. “Why do you ask?” He was opening for Charlie Parker’s group at The Three Deuces and thought we might like to meet him. A dream come true—I was going to meet God! The club looked like a railroad flat, with a bar and a couple of tables about as big as a soup bowl—you could barely put a drink on them. We sat in the back. After the opening set by Lennie and his trio, with Arnold Fishkin on bass and Harold Granowski (later Hal Grant) on drums, Bird played with the young Miles Davis and Max Roach, as well as Curley Russell on bass and (I think, as does Hal) Hank Jones on piano.

…..On set break, Arnold Fishkin brought us to the “dressing room” behind the back curtain to meet Bird, who was clean and straight, back east after his forced detox at Camarillo State Mental Hospital in California. He was sitting on the floor with a huge cherry pie and gave everyone a big slab. He asked Hal if he would sit in, but Hal demurred. Play with Bird? We could barely talk to him.

…..Bird and Lennie were the A side and B side of the new music. Tristano was an explorer, not really a swing player, as his rhythm was a little stiff, but his harmonic concept was incredible. Bird had all the other stuff. It didn’t matter what kind of horn he played, what mouthpiece, what reed—Bird made his sound. As Red Rodney said, he could play a tomato can.

…..On other occasions, we heard Art Tatum, Howard McGhee with Milt Jackson, and others I can’t remember. Fifty-Second Street was jumping. I’d walk up and down the street, just reading the marquees. A Coke cost a dollar, and we nursed it for four or five sets until the 4 a.m. closing, then caught our 5 a.m. bus back to Springfield. Hal told the waiter that he was my older brother, and they always were very accommodating. On Labor Day weekend we missed our bus home, so we slept in the bus station until the next bus left in the morning. The folks were a little worried, but they knew that Hal always took good care of their kid.

…..Studying with Tristano made me realize how much more work I needed to put in to be anywhere near the player I wanted to be. After I graduated high school, the woodshed beckoned, and I entered. I practiced scales, long tones, arpeggios, and assorted hot licks while walking a couple of hundred laps around the dining room table. Lennie had me write out what I felt was a natural-sounding improvised chorus on “Just You, Just Me,” which I’d learned jamming at the Phono Village. He accompanied me and discussed further options and weaknesses in the contrived chorus. He also gave me extensive keyboard harmony lessons, which I wasn’t ready for, and had me study his unique way of approaching scales and arpeggios.

…..When Tristano’s records with Lee Konitz and Warne Marsh came out in 1949, I analyzed and transcribed them, playing “Wow,” “Cross-Currents,” and “Marionette” with my school chum, Bob Rich, a great tenor man as well as a superior clarinetist (he played the heck out of Artie Shaw’s “Concerto for Clarinet” and had also memorized Shaw’s classic ”Stardust” solo). We were able to approximate the complex lines by Lee and Warne, who were two of the best “front line” players I ever heard. Their pitch and execution were unfailingly flawless, and the music, though often difficult and adventurous, always had a pulse—subtle, to be sure—but a pulse, nevertheless. As Lennie did not like sticks, his drummers were limited to using brushes. Bird was a fan of Lennie’s. Check out the way Bird executed on the Metronome All-Star date with Tristano, most notably on Lennie’s tune, “Overtime.”

…..I was earning money, too. I worked part-time for Dad’s sign company as a carpenter’s helper, and also held a five-night-a-week gig at the local Elks Club that Uncle Phil got me after the gigs at the Blue Grotto with Flip Brenner ended. I made $15 a night, $75 a week, darn good money right out of high school.

…..I had New York on my mind. Springfield had given me all it could. I knew that I wanted to be in the city which at that very moment was being invaded by the new leaders of the jazz revolution—Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Miles Davis, Fats Navarro, Sonny Rollins, Sonny Stitt, and Thelonious Monk. It was time to bite the Big Apple.

.

.

___

.

.

Excerpted from Life in E Flat – The Autobiography of Phil Woods. © 2020 Jill Goodwin. All rights reserved. Published by Cymbal Press, Torrance, CA USA cymbalpress.com. Excerpt published by permission of Cymbal Press.

.

.

.

.

Listen to Phil Woods play “You Must Believe in Spring” with Michel Legrand from the 1975 album Live at Jimmy’s, which Woods considered one of his most important recordings.

.

.

.