.

.

.

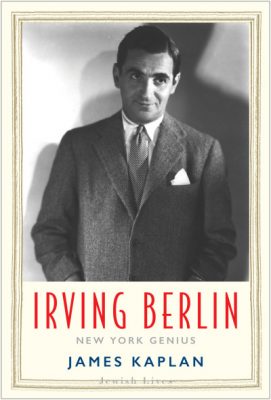

…..Irving Berlin will forever be known as the greatest songwriter of the golden age of American popular song. As with his music, his story as a self-made man whose brilliant career began as a singing waiter has endured for generations, and acclaimed author James Kaplan has taken it up in a hearty and sophisticated new biography, Irving Berlin: New York Genius.

…..I spoke with James about his book recently, and will publish the interview in the near future. Meanwhile, with the generous consent of the author and his publisher, Yale University Press, the following excerpt tells the story of how Berlin came to write his first major hit song, “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” and speaks to its historic musical and cultural significance..

.

.

_____

.

.

…..Nineteen ten was also a schizoid year for Berlin, the last year of apprenticeship and subservience. His salary came from his employer, the man whose name was on the door, the tall, bony fellow who sat at the piano, smiling at the world and grinding out tune after mediocre tune. The big money in Izzy’s bank account, though, was his and his alone. The question was whether he could make more of it, enough to light out on his own. He must have felt he could; on the other hand, there were his mother and occasionally unemployed sister in that nice apartment in the Bronx, and the monthly grocery bills and rent.

…..And so for the time being he played by Ted Snyder’s rules, reporting to work each day in suit and tie, turning out the product with fountain pen and paper, though bubbling with words and music of his own—no, words-and-music; with him it was almost always a unified entity—and drawn irresistibly, treacherously, to that Weser Brothers transposing piano.

…..The Ted Snyder Company was, like every other successful publisher on Tin Pan Alley, a mill: a warren of small noisy chambers where not only the house talent but song pluggers and postulant composers pounded out would-be euphonies on battered uprights in cacophonous chorus. It would have taken a powerful imagination, not to mention an ironclad will, to conceive fresh musical ideas under such conditions: Berlin had both. One day in the summer or fall of 1910, a ragtime-flavored melody came to him, at work, “right out of the air,” as he recalled a few years later. “I wrote the whole thing in eighteen minutes, surrounded on all sides by roaring pianos and roaring vaudeville actors.” The “thing”—the understatement is nothing short of colossal—was the tune (apparently lyricless at first) that would become “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.”

…..There is more than a touch of braggadocio to Berlin’s account, and his word choice is interesting. I wrote the whole thing in eighteen minutes. Most songwriters did their writing in musical notation, on staff paper. Irving Berlin did not, because he could not. Instead, when a new tune occurred to him, he hummed it or played a rudimentary piano version of it in the presence of a musical secretary (soon the Snyder Company would hire a brilliant young pianist named Cliff Hess for this express purpose), who then wrote down the notes. That was the melody. Getting the harmonies right was a more complicated process. This time the secretary would sit at the keyboard and play chords while Berlin, who inwardly knew precisely what sounds he wanted, would either approve or disapprove. The secretary would note the correct chords, and by and by, a full song would emerge.

…..But despite his later boasting, Berlin was unimpressed enough at first by this new Thing he’d “written” that he didn’t take the trouble to have it transcribed. Instead, he jotted a memo to himself about the melody, summing it up in a few words, then filed it away and forgot about it. It was only several months later, as he prepared to go on a winter vacation to Palm Beach—and here we must pause for a moment to consider the miracle of a twenty-two-year-old who in recent memory had sung for pennies in dives and slept in flophouses becoming a prosperous-enough businessman to vacation in Palm Beach— it was only as Irving Berlin puttered around the office before heading uptown to the newly built Pennsylvania Station to catch the Palmetto Limited, that he pulled from memory the melody that had popped out of the air months before. As a songwriter and journalist named Rennold Wolf wrote in a 1913 magazine article, “The Boy Who Revived Ragtime,”

Just before train time he went to his offices to look over his manuscripts, in order to leave the best of them for publica- tion during his absence. Among his papers he found a memorandum referring to “Alexander,” and after considerable reflection he recalled its strains. Largely for the lack of anything better with which to kill time, he sat at the piano and completed the song.

…..Wrote the words, in other words. Amazingly, not only could “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” have easily been lost to oblivion but for a phenomenal act of musical memory on Irving Berlin’s part; he also managed to throw the whole thing together while he waited for a train.

…..This was the exception that proved the rule: with the majority of his compositions, Berlin toiled for many hours, often through the deep watches of the night, sweating to come up with the right notes, the right words, the simplest essence of the song. Nothing, he discovered, was so complex as simplicity. “I sweat blood,” he said. “Absolutely. I sweat blood between 3 and 6 many mornings, and when the drops that fall off my forehead hit the paper they’re notes.”

…..The reality was less poetic. Woollcott said that Berlin suffered from “nervous indigestion”—a catchall that could have covered any number of disagreeable symptoms. “Most of his songs,” he wrote, “always postponed to that last minute and then turned out in a kind of frenzy of application, had been written by a small composer twisted with pain. This was so well known that whenever his neighbors in Tin Pan Alley saw him looking especially wan and spent and frail, they would exclaim bitterly: ‘Ah, hah, another hit I suppose!’ ”

…..But from the beginning, “Alexander” was different. It’s tempting to romanticize it as a thunderclap of sheer genius, but difficult to see it as anything else. As noted, 1910 was a journeyman year for Berlin, even if a profitable one: to look at a list of his titles for the period is to see a numbing succession of “Music by Ted Snyder”s, broken only occasionally by an all-Berlin composition, and only one of those times by a memorable one, “Call Me Up Some Rainy Afternoon.” As also noted, “Alexander” songs had an ignominious lineage in American popular music. In May, Snyder and Berlin published one of their own, “Alexander and His Clarinet,” a coon song in dialogue between a Colored Romeo (to quote another Berlin title from that year) and his Juliet, with a barely submerged Freudian subtext: “ ‘For lawdy sake [the female character sang], don’t dare to go, / My pet, I love you yet, / And then besides, I love your clarinet.’ ”

…..“Alexander’s Ragtime Band” was light-years beyond this hackwork. For one thing, it was about something, unlike the bulk of the era’s popular music (Snyder and Berlin’s included), most of which merely lent humorous or sentimental animation to stock characters and situations. What’s more, it was about something important. “Alexander” was a thrilling song, with a thrilling lyric, about the thrill of the new: a great new American art form, ragtime—which was, after all, jazz in embryo. It didn’t matter that the tune alluded to rather than embodied ragtime (it was really a march, with a mere hint of syncopation): it was a joyous tribute to African-American musical genius, the first great and lasting one in American popular song, from a Jewish-American musical genius. Even more: it was a celebration of America itself, a paean to—and very soon, a symbol of—emerging American cultural superpower.

…..“Alexander” also celebrated something else: its brilliant young composer. For in the end, who was Alexander but Irving Berlin himself?

.

___

.

Excerpted from IRVING BERLIN: New York Genius by James Kaplan. Copyright © 2019 by James Kaplan. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press

.

.

photo by Erinn Hartmann

James Kaplan, author of Irving Berlin: New York Genius

.

James Kaplan has been writing acclaimed biography, journalism, and fiction for more than four decades. The author of Frank: The Voice and Sinatra: The Chairman, the definitive two-volume biography of Frank Sinatra, he has written more than one hundred major profiles of figures ranging from Miles Davis to Meryl Streep, from Arthur Miller to Larry David

.

.

.

A 1911 recording of Billy Murray performing “Alexander’s Ragtime Band”

.

.

.