.

.

.

.

…..In Keith Hatschek’s The Real Ambassadors: Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong Challenge Segregation, the author tells the story of these three determined artists and the stand they took against segregation by writing and performing a jazz musical titled The Real Ambassadors. First conceived by the Brubecks in 1956, the musical’s journey to the stage for its 1962 premiere tracks extraordinary twists and turns across the backdrop of the civil rights movement. A variety of colorful characters, from Broadway impresarios to gang-connected managers, surface in the compelling storyline.

…..In the book’s prologue, published here in its entirety, the author writes about some of the musical’s challenges getting to the stage.

.

.

___

.

.

Keith Hatschek is author of three other books on the music industry and has directed the music management program at University of the Pacific for twenty years. Prior to becoming an educator, he spent twenty-five years in the music business as a musician, producer, studio owner, and marketing executive.

.

.

Praise for the book:

.

“With well-researched details and clear-eyed passion, Hatschek relates the story of the Brubecks’ creation, of the stars it brought into alignment (Louis Armstrong; Carmen McRae; the vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks and Bavan; and others), and of the social context of the early 1960s, and the timeless relevancy of its message. The story of The Real Ambassadors remains one of the most compelling chapters in the annals of music yet has been in danger of fading away. Hatschek’s book pulls it back into the spotlight, righteously explaining its enduring significance.”

– Ashley Kahn, music historian and author of A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album

.

“An inspiring story that places Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong at the center of jazz musicians’ fight in the 1950s and ’60s to overturn the impact of Jim Crow. It presents a shining example of the role of the artist citizen, a role that continues to be relevant today.”

– Nnenna Freelon, six-time Grammy-nominated jazz vocalist/recording artist

.

“Dave and Iola Brubeck’s musical The Real Ambassadors was decades ahead of its time, and though few paid attention to it at the time of its creation, its message feels even more relevant today than it ever did before. Keith Hatschek has dedicated over a decade of his life to researching this groundbreaking work, and his book, The Real Ambassadors: Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong Challenge Segregation, is the definitive story of an overlooked masterpiece. Anyone interested in the intersection of jazz, politics, and race, the impact of the jazz ambassadors’ State Department tours during the Cold War, and the inspiring, larger-than-life stories of seminal icons such as Dave Brubeck and Louis Armstrong, need to read this book.”

– Ricky Riccardi, Director of Research Collections at the Louis Armstrong House Museum and author of Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong and What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years

.

.

Excerpt © 2022, used by permission of University Press of Mississippi and Keith Hatschek

.

.

___

.

.

…..On the evening of September 23, 1962, as civil rights momentum was escalating to a fervor, a cast of thirteen talented artists came together at the Monterey Jazz Festival to perform The Real Ambassadors, a jazz musical challenging racial inequality. The culmination of five years’ work, the musical was written by well-known jazz musician Dave Brubeck and his wife, Iola, expressly to feature the most celebrated jazz musician in the world, Louis Armstrong. That night, they performed a slimmed-down one-hour “concert version” of what was envisioned as a three-act Broadway show, and their hope was that this premiere would help make that full production dream a reality. Supporting players included Carmen McRae, the vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks & Bavan, and Armstrong’s All-Star band, along with Dave Brubeck, Eugene Wright, and Joe Morello. The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s talented alto saxophonist, Paul Desmond, did not contribute to the recording or performance of the musical Iola Brubeck, who wrote the book and cowrote the lyrics for her husband’s songs, provided narration from a separate temporary stage to frame the musical numbers and explain the show’s themes.

…..The musical was inspired in part by the US State Department and its cultural ambassadors program, which had been sending American jazz musicians abroad beginning with Dizzy Gillespie’s 1956 tour. These jazz ambassadors toured overseas as a form of cultural diplomacy, promoting jazz as a uniquely American art form and touting it as a product of a free society. The Brubecks’ Real Ambassadors offered a nuanced portrait of these jazz ambassadors, drawing heavily on the experiences the couple had during their own State Department–sponsored global tour in 1958. Selling the notions of freedom and equality abroad was intended to present a contrast to the opposing totalitarian model offered by the Soviet Union. Ironically, however, while America’s Black jazz ambassadors were treated as royalty abroad, they still suffered racial prejudice at home on a daily basis.

…..The Real Ambassadors told the story of this irony, chronicling the hard road traveled by jazz musicians on tour for Uncle Sam in the 1950s. Led by a charismatic trumpeter and vocalist, “Pops,” and his love interest, the band’s vivacious female singer, “Rhonda,” the show’s lyrics and dialogue made plain the Brubecks’ belief that segregation must be overturned and that artists should take a stand to work toward social justice. The Real Ambassadors tackled controversial themes head-on, and some of its concepts could be considered blasphemous at the time—for example, posing the question “Could God be Black?” in the one of the musical’s most memorable songs, and dreaming aloud of a time when integrated music groups might be able to perform in Mississippi. Historian Penny Von Eschen argued that bringing the show to the stage at the height of the civil rights movement was not without risk. She stated:

“From our present day perspective, these types of statements defending civil rights and egalitarianism seem relatively mild, but when this was produced, America was at the height of the violent civil rights movement, and the federal government had not yet begun to take a stand to defend civil rights advocacy on a formal level. It was a very bold, controversial act at that moment in time.”

…..In evidence reconstructing the musical’s rocky path to the stage, we see that music industry power players such as Columbia Records president Goddard Lieberson warned the Brubecks’ to avoid such controversy if Dave and Iola wanted to see the musical realized.

…..In the early 1960s, the battle over civil rights in the United States was front and center on nightly newscasts, and the musical and its message were perfectly attuned to the national debate. At the time, powerful governmental, economic, fraternal, and institutional groups in the US were aligned to prevent the end of racial segregation by working actively to sustain the centuries-old practices of Jim Crow, ingrained practices that restricted the civil and societal rights of Black Americans and relegated them to second-class status. Even though the landmark 1954 decision reached in Brown v. Board of Education outlawed school segregation, local leaders scoffed at the law and maintained strict segregation throughout society, most prominently in the South. Powerful leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, and Dr. Ralph Abernathy, and organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), had raised their voices and were taking action to demand an end to segregation. Nonviolent actions including marches, boycotts, sit-ins, and teach-ins led by ministers, students, and activists were reported regularly in the media—especially when such peaceful acts caused violent responses from those strongly opposed to breaking the grip of Jim Crow. The nation was undergoing a crisis of unprecedented scope.

…..Within twelve months of the show’s debut, the tragic evidence of a nation divided would be apparent to the whole world. Only a few days after the show’s 1962 premiere, James Meredith enrolled to attend the University of Mississippi, the first African American student to do so. This led to riots that left three persons dead, six policemen shot, and dozens injured on the campus. A few months later, in May 1963, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference rallied students of all ages to march peacefully in protest to downtown Birmingham, Alabama, where the notorious commissioner of public safety, Bull Connor, ordered fire hoses used on the children, knocking many off their feet and shredding their clothes. This inhumanity was documented everywhere, from major networks’ nightly newscasts to the front page of the New York Times, where on May 4th, an iconic photo spread showed a Black high school student, Walter Gadsden, being attacked by Connor’s police dogs. Four months later, on Sunday, September 15, 1963, the murder of four young girls in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing further stunned the nation. News coverage of the protests dominated every form of media, and every day, Americans were reminded of the sacrifices being made by citizens of color.

…..Given this context, it is no surprise that The Real Ambassadors’ road to the stage was neither straightforward nor simple, spanning five years of the lives of Dave and Iola Brubeck, the creators and evangelists who were determined to bring the show to life. As Dave Brubeck’s own music career blossomed, he made his position on civil rights a cornerstone of his identity, both as an artist and an American. He was quoted frequently in interviews with a courageous mantra: that society would benefit from becoming color-blind. His ideals had come from observing how his father, Pete Brubeck, managed the large ranch in California’s Central Valley where the family lived in the 1930s. His father treated everyone with respect, hiring ranch hands who were white, Mexican, and Native American. The young Brubeck worked summers and after school as a ranch hand, side by side with these men, while attending the local public school in Ione, California, where he had a number of friends who were Native American. The pianist’s humanistic values advanced through his subsequent experiences as a young GI leading what was likely the first integrated US Army band, the Wolfpack, during World War II. After the war, Brubeck hired African American bassist Wyatt “Bull” Ruther as a member of the Dave Brubeck Quartet in 1951–52. In 1958, another Black bassist, Eugene Wright, became a mainstay of the quartet. Due to Jim Crow restrictions on integrated bands performing in the South, the Dave Brubeck Quartet had to cancel twenty-two dates of a 1960 Southern college campus tour. Brubeck refused to replace Wright with a white bassist, losing an estimated $40,000 in income. Having witnessed firsthand the sting of discrimination through his many musical friends and colleagues, Brubeck and his wife developed a deep-seated commitment to equal rights for all.

…..The Brubecks’ used their wits and resources to enlist the aid of every like-minded show business contact they had in order to make The Real Ambassadors a reality. Still, the performance itself was nearly torpedoed in the weeks leading up to the festival by Armstrong’s manager, Joe Glaser, a powerful man who saw much to lose and little to gain from such an endeavor. Likewise, Armstrong’s own wife, Lucille, feared that tackling difficult new songs might have been beyond her husband’s reach at that time, as he had suffered a near-fatal heart attack in 1959 while on the road in Italy and was weakened by forty years of nonstop touring.

…..The night of the premiere belonged to the cast. At its conclusion one critic noted that “the performers were rewarded with a standing ovation by 5,000 fans. Everyone applauded, some wept.” Critics unanimously praised the work as a bold statement supporting equal rights, telling the story of African American musicians with dignity and sensitivity in a way that deserved national attention. With these endorsements ringing in their ears, the Brubecks’ five-year effort to bring the full production to Broadway or television felt within reach. But the growing success of the Dave Brubeck Quartet, which came to be the most popular small jazz ensemble in the world, eclipsed The Real Ambassadors, until it reemerged in the 1990s as a vital, if overlooked piece of Brubeck’s and Armstrong’s careers. In the twenty-first century, it has enjoyed three revivals, which have proven that the timeless messages in it still ring true today.

…..Documenting a largely untold history of Black and white jazz artists teaming up to challenge Jim Crow, with Cold War tensions and the emerging civil rights movement as a backdrop, the tale of The Real Ambassadors is a story within a story. Wrapped around the production’s fictional plot was a very real account of struggle in the civil rights era, as Louis Armstrong and Dave and Iola Brubeck fought to present a musical designed to foment social change. Understanding its complicated road to the stage against the backdrop of its underlying message can provide insight today, at a time when race relations are once again at the forefront of national discourse. These talented artists demonstrated that challenging racism, xenophobia, gender bias, and other hate-based creeds requires logic, compassion, wit, and above all, dogged persistence—and that the reward may come in unexpected forms and on unexpected timelines. Dave and Iola Brubeck and the cast of The Real Ambassadors collectively made a bold social and political statement at a time when many Americans were angry, confused, and in search of answers—lifting their voices to help bring about social change one song at a time. They can be seen as part of a wave of mid-twentieth-century American musicians, filmmakers, and artists who spoke out loudly against discrimination in direct response to their troubled times. This story illustrates the vital role that artists can play as ambassadors of the truth, speaking for equality and justice, both in their own time and through their art, for all times. It demonstrates the importance of keeping our eyes on the prize, even if we may never see that prize fully realized in our own lifetime.

.

.

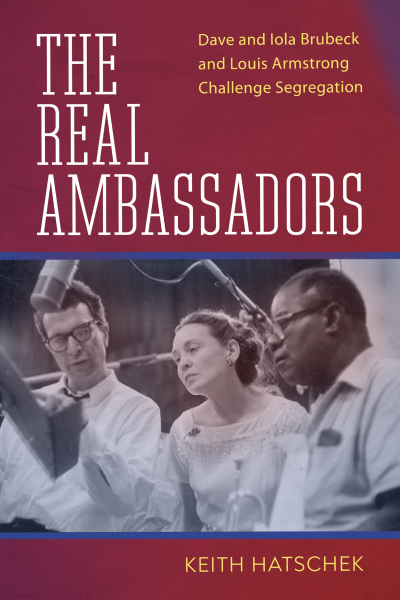

The cast of The Real Ambassadors at their daylong rehearsal, Monday, September 17, 1962, at San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel. Pictured back row, L-R, Howard Brubeck, Danny Barcelona, Eugene Wright, Joe Morello, Billy Cronk, Dave Lambert, Yolande Bavan, Jon Hendricks and Iola Brubeck. Front row, L-R, Trummy Young, Carmen McRae, Louis Armstrong and Dave Brubeck. Not shown, clarinetist, Joe Darensbourg. Credit: Photo by V.M. Hanks. Brubeck Collection, Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library, © Dave Brubeck. [photo used by permission of Keith Hatschek]

.

.

.Excerpt © 2022, used by permission of University Press of Mississippi and Keith Hatschek

.

.

Click here to access the publisher’s page for this book

.

.

Listen to the 1962 recording of “The Real Ambassadors,” from the album of the same name [Legacy/Columbia]

.

.

.