.

.

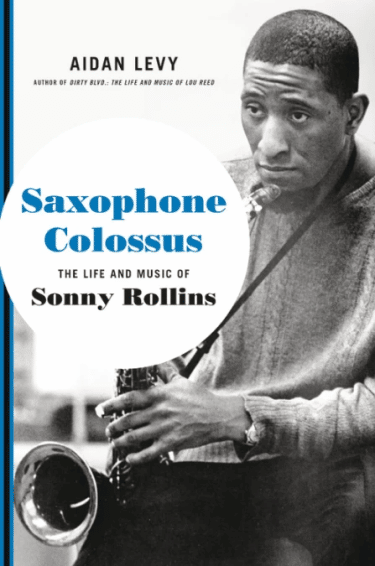

Saxophone Colossus: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins

by Aidan Levy

[Hatchette Books]

.

.

___

.

.

…..In his new book, Saxophone Colossus: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins, the author Aidan Levy appropriately describes his subject as “one of the greatest jazz improvisers of all time,” a “bridge from bebop to the avant-garde,” and “a lasting link to the golden age of jazz.”

…..I’ve had the opportunity to read this book, which re-awakened my interest in his music, provoked me to listen to his more recent recordings with an open ear, and helped me to better understand his life challenges, his extraordinary dedication to his work, his quest for social justice, and his connection to his spiritual awareness.

…..I recently interviewed Mr. Levy about this book (an interview that will soon be published on Jerry Jazz Musician), and, in anticipation of it, he and his publisher [Hatchette] have graciously allowed me the privilege of sharing an excerpt from the book with readers.

…..In it, Levy describes how a 16-year-old Sonny Rollins caught the ear of the 29-year-old Thelonious Monk, a man Rollins looked up to “as a father figure – a guru, really,” whose musical principles “deeply informed his artistic development.”

.

.

___

.

.

Excerpted from SAXOPHONE COLOSSUS: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins by Aidan Levy. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

.

.

…..In his senior year of high school, Sonny met a brilliant pianist many considered jazz’s most mysterious man, Thelonious Sphere Monk. Sonny had first heard Monk in 1944 when he bought a [Coleman] Hawkins ten-inch 78 with “Drifting on a Reed” and “Flyin’ Hawk” as the B-side: Monk’s recording debut. “I got this record and rushed home to play it,” Sonny recalled. “It had a pianist on there who had . . . a little different style.” Monk immediately stood out. His staccato accents to Hawkins’s lyrical vibrato created a beautifully dissonant counterpoint, connecting the stride-piano tradition of James P. Johnson and Willie “the Lion” Smith with the sweeping improvisational vision of Art Tatum: artful and restrained, bracingly new, but not wholly detached from the past. To Sonny, there was a straight line from Fats Waller to Monk. “Everything about Monk’s playing—the harmonies, the rhythmic sense, the fact that he played stride-style piano,” Sonny said, “that’s right up my alley. Monk didn’t play a lot—spread across the two tracks, Hawkins scarcely gave him forty-five seconds of solo time—but when he did, it made an impression.

…..Monk had endured a tumultuous year himself. After Coleman Hawkins disbanded his quartet to join Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic, Monk was out of a job. He joined Dizzy Gillespie’s big band, only to be publicly fired onstage at the Apollo when he lost track of time at a nearby bar. By the end of 1946, Monk was so out of work that he let his union membership lapse. Yet Monk’s ill fortune was Sonny’s kismet. Monk continued frequenting jam sessions: Club 845 on Prospect Avenue on Sunday afternoons, at Minton’s on Monday nights, or at pianist Mary Lou Williams’s apartment. On one of these occasions, a sixteen-year-old saxophone prodigy from Sugar Hill caught the ear of the twenty-nine-year-old Monk.

…..“I played a little job when I was starting out at a club in Harlem,” Sonny recalled. He was opening for the man known as the high priest of bop, so the pressure was on. Sonny rose to the occasion. “Monk was a very unassuming guy,” Sonny said. “He indicated to me that he liked my playing. I think that was the first time I met Monk.”

…..Not long afterward, trumpeter Lowell Lewis was invited into Monk’s bedroom studio. “While we were still in high school, Thelonious Monk somehow found out about Lowell and gave him a job to go to Chicago,” Sonny said. “So Lowell went with Thelonious to Chicago for a week while we were still in high school. And after that, he said, ‘Come on, I’m going to get you in Monk’s band.’ ”

…..When the last bell rang at school, Sonny’s classes truly began. They’d make the pilgrimage downtown from Franklin High School in East Harlem to Monk’s monastery all the way on the West Side. “So somehow [Lowell] worked it out so they finagled this other tenor player out of the band, and he brought me by his pad to play, and Monk liked me and hired me.” The feeling was mutual. “Monk was great to me. He was older than me, maybe thirteen years older or so, and I looked up to him as a father figure—a guru, really.”

…..Sessions began informally. “He used to sneak me into bars after school,” Sonny later recalled. But when they migrated back to Monk’s apartment, Monk taught Sonny about “the geometry of musical time and space.” The lessons were not didactic. “I don’t think he was particularly trying to mold me,” Sonny said. “He was the type of guy who would never tell you what to play; he wouldn’t try and make you do it this way or that way. If he liked you, here was the music, and that’s that.” Monk immediately liked Sonny’s originality. “Monk would say, ‘Yeah, man, Sonny is bad. Cats have to work out what they play; Sonny just plays that shit out the top of his head.’”

…..By the time Sonny began showing up at his informal rehearsals, Monk had begun to distance himself from bebop, the form he helped create. “Mine is more original,” he said in 1948 of the countless bebop imitators who had flooded the scene. “They think differently, harmonically. They play mostly stuff that’s based on the chords of other things, like the blues and ‘I Got Rhythm.’ I like the whole song, melody and chord structure, to be different. I make up my own chords and melodies.”

…..Sonny quickly became a fixture at Monk’s bedroom jam sessions, where he rehearsed his complex compositions. Monk lived with his family in San Juan Hill, in the Phipps Houses between Amsterdam and West End Avenue. The neighborhood had been a hub of African American bohemian life, where Monk’s idol James P. Johnson birthed the Charleston in Jungle’s Casino after witnessing longshoremen from South Carolina doing the dance. Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Max Roach regularly played at jam sessions at the Lincoln Square Center; up the block, Bird sometimes played dances at the St. Nicholas Arena. Yet some of the most innovative music in San Juan Hill was emanating from Monk’s humble tenement apartment.

…..Sonny routinely walked through the building’s entrance court with his tenor, past the steam pipe and the inlaid star mosaic on the floor. Monk insisted on a dapper style regardless of the occasion—bespoke suit, horn-rimmed glasses, well-manicured goatee.

…..It was always a family affair. “When Monk took me under his wing,” Sonny said, “I used to go down to his house and hang out with [Monk’s wife] Nellie and the family.” The Monks lived in a cluttered two-bedroom apartment on the ground floor, with a tin ceiling, faded linoleum, and a pristine refrigerator. Sonny would walk through the kitchen to Monk’s spartan, dimly lit bedroom and studio. A Klein upright took up as much space as Monk’s worn-out cot, barely large enough to accommodate the pianist’s large frame. The inner sanctum was a jazz shrine with a kind of visual syncopation: on the ceiling, next to a naked red lightbulb, Monk plastered a 1939 letter-size portrait of Billie Holiday, white flower in her hair, hung at a canted angle. Sarah Vaughan commanded a spot on the wall; Dizzy Gillespie’s headshot hung proudly over the piano, signed “To Monk, my first inspiration. Stay with it. Your boy, Dizzy Gillespie.” Framed photos and tchotchkes took up all the available real estate atop the piano. A lone window looked out on an alleyway.

…..Completing this cramped collage, musicians would jockey for space between the dresser, cot, piano, and chair. Sonny and Lowell Lewis would regularly see Idrees Sulieman, Kenny Dorham, Julius Watkins, and others. Sonny brought along other members of the Counts of Bop, especially Jackie McLean, who lived across the street from Lewis, and Arthur Taylor, to absorb as much of Monk’s influence as they could. Others from outside their group, such as pianist Randy Weston, also joined in.

…..To Sonny, Monk was “the old master painter,” and the musicians who gathered at his apartment were the canvas. “Monk would have what seemed to be way-out stuff at the time and all the guys would look at it and say, ‘Monk, we can’t play this stuff . . .’ and then it would end up that everybody would be playing it by the end of the rehearsal,” Sonny mused. “It was hard music.”

…..Some sessions were more like lessons than rehearsals. Despite Monk’s admonition against using established harmonic structures, it was not as though he didn’t know the Great American Songbook. If a young musician really wanted to learn standard repertoire, Monk was the authority. “He knew the changes to all the songs,” recalled Arthur Taylor. “Like Rollins and McLean. When they want to know a song, they go to Monk’s house, and Monk can give you the right chords. When you get the chords from Monk, it’s right. . . . You can improvise on it or whatever you want to do, but he’ll give you the right stuff.” In performance, though, Taylor recalled, Monk would “play only his own stuff.”

…..Some people heard all that dissonance in Monk’s playing and thought he didn’t know the standard tunes. But to those who knew, they heard the opposite: Thelonious broke all the rules because he knew them better than anyone. Two of Monk’s favorite mantras were “Always know” and “Play yourself.” His message was clear: If you didn’t “always know” the tune like the back of your hand, even the melody could sound wrong. Before you could “play yourself” on a standard, it had to become a part of you. And in order to write your own standards, you had to know all the others first. Sonny took this lesson to heart.

…..Later, when Sonny was asked what Monk had taught him, he said, “Nothing.” What did he learn from him? “Everything.”

…..As Monk was sketching out what would come to be standards—“Ruby, My Dear,” “In Walked Bud,” and “Off Minor”—Sonny and his crew were some of the first to workshop these brilliant, beguiling compositions, with their intervallic leaps and dissonant resolutions, vexing rhythms and charged silences. Monk epitomized the sound of surprise.

…..At these after-school sessions, Monk defied his mythic public persona. “Monk was an enigmatic guy, but he was one of the best people I’ve known— completely honest,” Sonny said. “He really helped me out, took me under his wing, so to speak. He’s a beautiful person. I get so upset when people try to depict Monk as being some kind of a weird guy or a crazy guy. It’s so completely opposite from reality.”

…..Monk mostly led by example, but when he did speak, he imparted his wisdom in homespun adages, some of which were later taken down by saxophonist Steve Lacy, another acolyte. “Those pieces were written so as to have something to play, and to get cats interested enough to come to rehearsal”; “A genius is the one most like himself”; “What should we wear tonight? Sharp as possible!”; “A note can be as small as a pin or as big as the world, it depends on your imagination”; “What you don’t play can be more important than what you do play”; “Just because you’re not a drummer, doesn’t mean that you don’t have to keep time”; “Pat your foot and sing the melody in your head when you play. Stop playing all those weird notes, play the melody.” He would often remind his protégés that “Know” was a palindrome for Monk, with the M flipped upside down. When Sonny played a phrase, he learned to examine it from all perspectives.

…..For Sonny, Monk’s approach to music became a secular religion. “Anything was possible with Monk,” Sonny said. “That’s why we called him the High Priest . . . because the spiritual element was of a high order.” Sonny was a monk in Monk’s temple, and everything Monkish, from the focus on the melody to the rhythmic angularity to the staccato attack to the fine threads, he absorbed into his own original style, translating San Juan Hill to Sugar Hill, piano to the saxophone. He learned the meaning of originality from one of the most original artists of the century, any century. And he learned it from an artist who had been unfairly portrayed as disconnected from reality. Nobody was realer than Monk.

…..“When you’re around those musicians, man, they make you understand without conversation that your story is as important as every story told,” said drummer Perry Wilson, who later played in Sonny’s band. “Sonny used to tell us stories and there was a little bit of humor in it. He’d say, ‘Monk and I, man, I could go by his house, man, and we could sit for eight or ten hours, and never say a word to each other. Be in the same room. And after ten hours, ‘Hey, man, I’m gonna cut out.’ ‘All right, Newk, I’ll see you man.’ Just that energy in the room . . . and you know when they got together and made some music it’s way the fuck up here. Right? . . . They know how to call and answer; they know how to finish each other’s sentences, so to speak.”

…..At one of these rap sessions on Sixty-Third Street, Monk said, “‘Man, if there wasn’t music in this world, this world wouldn’t be shit,’” Sonny recalled. “It was sort of an oversimplification, but the way he said it, I said, ‘Wow, exactly.’” Nietzsche had said the same thing.

…..For Sonny, Monk provided a sense of belonging during an alienating time in his life. He helped him become himself. As Sonny’s sound crystallized, many of Monk’s principles—melodicism, space through sound and silence, sartorial flourishes, a Sisyphean work ethic, an encyclopedic knowledge of the tradition, all of that ugly beauty—deeply informed his artistic development.

…..Soon, Sonny was applying his lessons with Monk to his own practice sessions. “I remember one moment that I had when I was playing with some of my friends,” Sonny said, recalling one of the many times he rehearsed with Lowell Lewis after school. “I was rehearsing with him one day and was taking a solo in which I was able to manipulate the time in a way that drew his attention. He made a remark about it, and then I realized, oh, I must really have something.”

.

.

___

.

.

Excerpted from SAXOPHONE COLOSSUS: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins by Aidan Levy. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

.

.

Listen to the 1954 recording of Sonny Rollins (saxophone), Thelonious Monk (piano), Tommy Potter (bass), and Art Taylor (drums) playing “The Way You Look Tonight.” [Universal Music Group]

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read other book excerpts

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support Jerry Jazz Musician

.

.

.