.

.

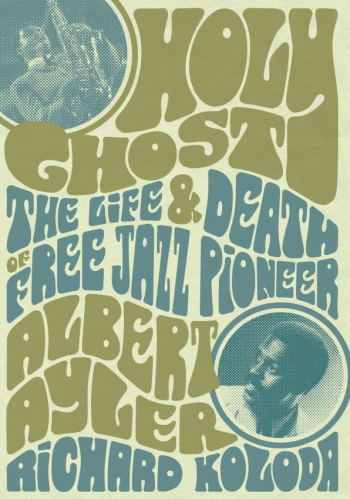

Holy Ghost: The Life & Death Of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler

by Richard Koloda

.

.

___

.

.

…..Albert Ayler’s music is certainly not for everyone. As a pioneer of free jazz – the experimental music that turned away from jazz’s musical roots during the era of the mid-1960’s Black Arts Movement- the saxophonist was a controversial figure considered by many to be a charlatan, even insane.

…..The renowned jazz writer John Szwed wrote that Ayler’s music “was so startling that some called it a scandal,” but whose work as a free jazz pioneer “pushed the vocabulary of John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders as far as they could be pushed.” The jazz writer Val Wilmer – an early proponent of Ayler’s art – wrote that he “remains one of the great visionaries of American music.”

…..Richard Koloda, longtime friend of Ayler’s brother (and trumpeter) Donald, and author of Holy Ghost: The Life & Death of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler, writes that “like most geniuses, Ayler was misunderstood in his time. His divine messages of peace and love, apocalyptic visions of flying saucers, and the strange account of the days leading up to his being found floating in New York’s East River are central to his mystique, but they are a distraction, overshadowing his profound impact on the direction of jazz as one of the most visible avant-garde players of the 1960s and a major influence on others, including John Coltrane.”

…..I am in the midst of reading Koloda’s engrossing history of Ayler, and will soon be interviewing him about his subject. (That interview will appear in Jerry Jazz Musician in March). The book’s preface that follows introduces the reader to his influence on jazz, and to the compelling and often misrepresented history of Ayler’s life story.

.

.

___

.

.

Excerpted from Holy Ghost: The Life & Death Of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler by Richard Koloda, published by Jawbone Press. Text © 2022 Richard Koloda

.

.

…..Albert Ayler was the spirit that inspired John Coltrane to begin his avant-garde explorations, and that same spirit inspired all of Coltrane’s successors as well. But like many geniuses ahead of their time, Ayler was a polarizing figure. Some critics considered him a charlatan, others a heretic for dismantling the traditions of jazz. Some simply considered him insane. His divine messages of peace and love, visions of flying saucers, and the strange account of his final days leading up to being found dead in New York City’s East River are central to his mystique, but they are also a distraction.

….. The mysterious manner of Ayler’s death tends to overshadow the blistering impact he had on the direction of jazz to come. Yet while there exists a posthumous cult surrounding John Coltrane, Ayler’s spirit, per Peter Niklas Wilson, ‘seems to have evaporated into unreality. Albert Ayler was born to the myth, one to be dark and mysterious.’

….. And that is the shock. Coltrane is a household name. Ornette Coleman is spoken of in legendary terms, and Eric Dolphy is revered as a tragic saint who died before his time. But Ayler’s greatest influence today is on rock musicians. At the time of his first released recording, the jazz world considered the outer fringe to be Coleman’s 1961 album Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation, Coltrane and Dolphy’s interplay on ‘Africa’ (from Coltrane’s fourth studio album of the same year, Africa/Brass), and pianist Cecil Taylor’s ‘D Trad, That’s What’ (from 1962’s Nefertiti, The Beautiful One Has Come). Against even these, however, Ayler’s first recording was further out than what many felt was acceptable. Though Taylor was as radical as Ayler, his musical development took place over an extended period of time, allowing the jazz world to assimilate those ideas. Ayler did not have the same opportunity to live a full lifespan.

….. Ayler did, however, change the course of jazz in influencing Coltrane, and by returning jazz to the roots of collective improvisation. His Spiritual Unity was both praised and ridiculed when it was released in 1964. Today it is recognized as a landmark in free jazz. He would also, in what some considered an ill-advised venture into pop-jazz, augur the R&B trend that jazz would follow after his passing. The temptation is to speculate where his genius would have taken him had he been given a second chance by his label of the late 60s, Impulse!, and by life itself.

….. Within a half-decade of being booted off the stage in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio, Ayler was headlining the Newport Jazz Festival in Europe. A mere three years after that, in July 1970, he staged the greatest triumph of his career, playing at the Maeght Foundation on the French Riviera, where he was called back onstage for ten encores. Despite the triumphant joy of that evening, captured on tape for the live album Nuits de la Fondation Maeght, Ayler had a mere four months left to live.

.

*

.

….. Ayler’s story compares to classic Greek tragedy, whether it is the oft-used line about being misunderstood in his homeland or his committing suicide to expiate the guilt he felt over firing his troubled younger brother, Donald, from his band. His story compels us to listen to his spiritual cries.

….. This first exhaustive English-language biography of Ayler has been in the works for over twenty years. When I interviewed Donald and his father, Edward, for my jazz show on Cleveland State University’s WCSB 89.3 FM, my preconceived notions about Albert quickly fell away, and I hope the reader’s assumptions about this saxophone giant will fall by the wayside as well. This work attempts to correct a myriad of misinformation, not least the story of his corpse being tied to a jukebox and tossed in the East River. I have also uncovered facts that contradict Ayler’s statements to interviewers, such as his claim that he joined the US Army to gain musical experience (it was more likely to avoid paying child support), or that he was born in a ghetto.

….. Holy Ghost also corrects the historical record. It was convenient for critics to link Ayler with the rising Black Power movement, ignoring the reality that, to Ayler, music held a profoundly spiritual power—it was the ‘healing force of the universe,’ as he put it. It also dispels the myths surrounding Ayler’s mental health that some critics have used to devalue his music, among them reactions to the apocalyptic visions of flying saucers and the sword of Jesus that Ayler shared in Amiri Baraka’s magazine The Cricket in 1969.

….. Against critical consensus—and Ayler’s own assertions—this book also attributes the later changes in Ayler’s musical direction to the limited resources of his trumpet-playing younger brother, Donald, which necessitated the shift from the avant-garde playing of Albert’s previous trumpeter, Don Cherry, toward the pop-jazz of his later years.

….. Since I began working on this book, I have seen reissues that establish Ayler as a creator whose influence is acknowledged by rock musicians such as Patti Smith, who once said that her album Radio Ethiopia was ‘a lot like Albert Ayler.’ John Lurie of The Lounge Lizards wrote a ballet called The Resurrection Of Albert Ayler. Saxophonist Mars Williams, who has played with new-wave group The Psychedelic Furs and industrial-metal pioneers Ministry, has a band called Witches & Devils that plays Albert Ayler’s music and has established a unique tradition of performing Ayler-inspired Christmas concerts in the US and abroad. A Swedish free-jazz group, The AALY Trio, led by saxophonist Mats Gustafsson, plays Ayler compositions, often in conjunction with Chicago-born reedman Ken Vandermark.

….. Ayler’s work has cast an especially long shadow across New York’s own hugely influential rock scene. Ironically, in the years since his death, more guitarists than saxophonists seem to have been inspired by Ayler, among them Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd, of the post-punk group Television, and Robert Quine of the Voidoids. Noise-rockers Sonic Youth named their 2000 album NYC Ghosts & Flowers in acknowledgement of Ayler’s influence, while their New Jersey neighbor (and Tom Waits and John Zorn collaborator) Marc Ribot has also named Ayler as a guiding force and recorded a collection of Ayler compositions on his 2005 tribute album, Spiritual Unity. He’s not the only one: one-time Captain Beefheart guitarist Gary Lucas and folk-punk firebrands Violent Femmes have also recorded his compositions.

….. Lou Reed’s attempts at free jazz; The Stooges’ sonic onslaught in Fun House; the guitar maelstroms of Comets On Fire—all bear Ayler’s thumbprint. In France, there is even a record label named after him, Ayler Records. Closer to home, Revenant Records, founded by the equally revered American primitive guitarist John Fahey, issued a definitive Ayler box set, the Grammy-nominated Holy Ghost: Rare And Unissued Recordings (1962–70), in 2004, which appeared almost simultaneously alongside Kasper Collin’s critically acclaimed documentary film My Name Is Albert Ayler (both projects list me as a contributor). And neither has Ayler’s stature as a genius diminished among the jazz cognoscenti: DownBeat magazine inducted him into its Hall Of Fame in 1983.

….. Two decades after his death, Ayler’s oeuvre finally began to receive the scholarly attention it deserves: in 1992, Bowling Green State University graduate student Jeff Schwartz published the ebook Albert Ayler: His Life And Music; the following year, University Of Wisconsin–Madison student Jane Martha Reynolds made him the partial subject of her doctoral dissertation, Improvisation Analysis Of Selected Works Of Albert Ayler, Roscoe Mitchell And Cecil Taylor; and English fan Patrick Regan has maintained the long-running website Ayler.co.uk since June 2000. In 2010, several groups marked the fortieth anniversary of Ayler’s death with tribute concerts; others chose to celebrate his birth. The First Annual Albert Ayler Festival took place in July 2010 on Roosevelt Island, New York. It had been organized by ESP-Disk’, the record label most closely associated with Ayler and his music.

….. In adding to the wealth of material already out there, the true goal of Holy Ghost is to draw attention away from the circumstances surrounding Ayler’s death and bring it sharply back to the legacy he left behind. Doing so demands confronting those who have marginalized, maligned, and spread misinformation about Ayler in order to further their own agendas. He was a character as interesting as any that could have been created by a Hollywood screenwriter. It is hoped the reader will enjoy finding out why, just as much as I enjoyed researching Ayler’s life.

.

.

___

.

.

Excerpted from Holy Ghost: The Life & Death Of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler by Richard Koloda, published by Jawbone Press. Text © 2022 Richard Koloda

.

.

Richard Koloda has a master’s degree in Musicology from Cleveland State University, having written a thesis on the piano music of Frederic Rzewski. He was a contributor to the critically acclaimed documentary My Name Is Albert Ayler by Swedish filmmaker Kasper Collin and a consultant on Revenant Records’ ten-CD retrospective of Ayler, Holy Ghost: Rare And Unissued Recordings (1962–70), which has been called ‘the Sistine Chapel of box sets.’ Richard lives in Wayland, Ohio, where he practices law. When he is not in court, he is working on his second book (not about music).

.

.

Listen to the 1964 recording of Albert Ayler playing “Spirits,” from the album Witches and Devils, with Norman Howard (trumpet); Henry Grimes (bass); and Sonny Murray (drums).

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read other book excerpts

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publishing efforts of Jerry Jazz Musician (thank you!)

.

.

.