.

.

.

.

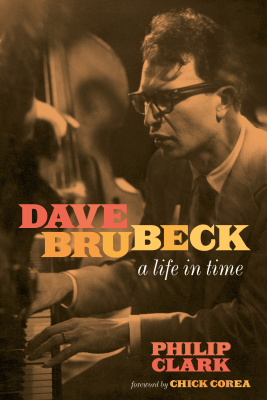

…..I am in the midst of reading Philip Clark’s Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time (Da Capo), and will soon be interviewing him about the book and the enigmatic and extraordinary pianist, composer, and band leader.

…..Clark is an excellent writer, and his book is an impressive blend of expert musical analysis, the sociology that surrounded and informed much of Brubeck’s art, and an appropriate amount of esteem reserved for his legendary subject.

…..Much of the book revolves around conversations and details that emerged during a ten day period in 2003 when, according to the book’s publisher, the author was “granted unparalleled access” to Brubeck. The result is that “Brubeck opened up as never before, disclosing his unique approach to jazz; the heady days of his ‘classic’ quartet in the 1950s-60s; hanging out with Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, and Miles Davis; and the many controversies that had dogged his 66-year-long career.”

…..In the book’s introduction – published here in its entirety with the consent of the publisher – Clark writes about the origins of the book, and his interest in shining a light on how Brubeck, “thoughtful and sensitive as he was, had been changed as a musician and as a man by the troubled times through which he lived and during which he produced such optimistic, life-enhancing art.”

…..

.

___

.

.

“[A]n engaging new biography… we feel the grain and texture and historical weight of single moments, but only because we also understand the larger picture. It’s a rare jazz biography that gives us both, so eloquently.”

-The Sunday Telegraph

.

.

.

photo Nina Hollington

Philip Clark is a music journalist who has written for many leading publications including The Wire, Gramophone, MOJO, Jazzwise, and The Spectator. He also writes for the Guardian, Financial Times, London Review of Books, and the Times Literary Supplement. He trained as a composer but these days prefers to produce his own sounds playing piano as part of a weekly free improvisation workshop. Clark lives in Oxford with his wife, two children, two cats, and more recorded music than he can ever listen to.

.

.

.

Excerpted from Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time by Philip Clark. Copyright © 2020. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Used by permission.

.

.

___

.

.

Once I had my title, not writing became more of a problem than sitting down to begin.

…..A Life in Time was a title that encapsulated the classic biographical model of “the life and times,” but it also opened up the terrain. The project was not to write a book that marched through Dave Brubeck’s life chronologically— casually observing, perhaps as an aside, that shortly after his quartet recorded “Take Five” in 1959, Vice President Richard Nixon flew on a trade mission to Moscow and Billie Holiday died. The plan instead was to thread his life back through the times that formed it. Brubeck saw active service as a solider during the Second World War; he led a commercially successful, racially mixed jazz group during some of the ugliest days of American segregation; and in the late 1960s and early 1970s he created a series of large-scale compositions that reflected variously on issues of race, religion, and the messy politics of an uncertain era. Threading his life back through these times was both a musical and a social concern—I wanted to shine a light on how Brubeck, thoughtful and sensitive as he was, had been changed as a musician and as a man by the troubled times through which he lived and during which he produced such optimistic, life-enhancing art.

…..As a biographer in search of a title, I was handed a gift by Brubeck, even if it took me a while to realize it. He was a man obsessed with time. From the moment he founded the Dave Brubeck Quartet in 1951 to only eighteen months before his death at the end of 2012, Brubeck spent much of his life touring the world, which adds up to sixty years of playing concerts in every continent of the world, including some countries that today would be too dangerous to contemplate visiting.

…..He was also a man impatient with time. Finding time to play jazz, time to compose, and time to devote to his wife Iola and their six children were all important to Brubeck, and with only so many hours in the day, one solution was to overlap those activities. Compositions originally written for his extended sacred pieces were adapted for his jazz groups; and, if you want to spend more time with your teenage children, one sure way to know where they are every night is to play jazz with them. Beginning in 1973, Brubeck toured with three of his sons— Darius, Chris, and Dan—as Two Generations of Brubeck and the New Brubeck Quartet, his initial reluctance to embrace their newfangled cultural reference points—which included rock, funk, and soul music—quickly forgotten.

…..But that word, time, also had another meaning altogether. Whenever I interviewed Brubeck, it never took long for two key terms to emerge: polytonality and polyrhythm. Polytonality—music sounding in two or more keys simultaneously— and polyrhythm—overlays of different rhythmic pulses and grooves—were, like the attitude he took toward life, techniques that allowed obsessions and tics to coexist. Brubeck plied his music with overlaps: between musical cultures in “Blue Rondo à la Turk,” which combined an indigenous Turkish rhythm with the blues, and in “Three to Get Ready,” which squared the circle of a waltz by inserting bars of 4/4; between different time signatures, like his version of “Someday My Prince Will Come,” which managed to be in 4/4 and 3/4 at the same time; between the radically diverse range of musical styles through which he waded in his improvised solos—no sweat as Liszt flowed into James P. Johnson.

…..And time also meant time signatures. “Take Five” in 5/4 time, “Blue Rondo à la Turk” in an asymmetrically arranged 9/8, “Unsquare Dance” in 7/4—before Brubeck, no jazz musician had worked so consistently, or so successfully, with extending metric possibilities. For all their bold innovations and harmonic daring, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Thelonious Monk, the occasional waltz aside, kept to 4/4 time, but Brubeck’s experiments with time signatures became his calling card. In the US, May 4—5/4—has become an unofficial Dave Brubeck Day and Twitter meme; and Tchaikovsky might have composed a famous waltz in 5/4 time in his Pathétique Symphony, but Brubeck came to own the idea of 5/4 time in the way that Van Gogh owned the sunflower and Philip Glass the arpeggio—which meant he owned nothing at all. Anyone can paint a sunflower or play music in any time signature they like; but Brubeck’s 5/4 time stuck in the public imagination, to the point that he and it became inseparable.

…..Even before he had recorded a note of music in 5/4 or 7/4, Columbia Records bosses sniffed something in the air and decided to call his first studio album for the company Brubeck Time; and after the soar-away triumph of Time Out, Brubeck followed up with Time Further Out, Time Changes, Countdown—Time in Outer Space, and Time In. His gift to any prospective biographer, especially one searching for a title, was that word, time, which needed to feature as part of my title—but in a more meaningful way than a mere wisecracking play on words. Reconciling all those connotations of time, from the broadly historical to the directly musical, became my way forward. A structure pieced itself together as I took time to think through all these various meanings of time.

…..“Go back to the music if in doubt” became my mantra as I wrote, and the structural inner workings of Brubeck’s music led the way from the get-go. The story within a story of the blues and Turkish music in “Blue Rondo à la Turk” and of 3/4 versus 4/4 in “Three to Get Ready,” and Brubeck’s knack for nesting one time signature inside another, freed up time: no need to slavishly adhere to the chronology. I was interested in investigating how one aspect of his life illuminated another against the panorama of American history; and if you’re wondering why the first chapter begins in 2003 and then flips back to 1953— when the Dave Brubeck Quartet was touring in a package with Charlie Parker—that is why. Opening the book by explaining where Brubeck’s music stood in relation to Parker’s—who was then considered to be the very embodiment of modern jazz— journey straight to the heart of the music.

…..And another reason to cut direct to the chase, leaving Brubeck’s birth until later, was that I didn’t want to wait for the chronological narrative to catch up with my own role as an embedded reporter. In 2003, I shadowed the Dave Brubeck Quartet (then featuring Bobby Militello, Michael Moore, and Randy Jones) during a ten-day tour of the UK. I couldn’t make every gig, but as the quartet traveled between their rented apartment in Maida Vale, West London, and Brighton, South- end, Manchester, and Birmingham, I had the privilege of sitting next to Dave on the bus and we talked and talked, sometimes late into the night; I also spent time with Brubeck and his wife Iola in their Maida Vale flat. Ostensibly this extended inter- view was for a feature commissioned by the British jazz mag- azine Jazz Review—published as “Adventures in the Sound of Modernist Swing” in July 2003—but Dave gave me hours’ worth of material, many more words and memories than could be stuffed into a 3,500-word article. I always worried that my original article, rushed out in a couple of days to satisfy press dead- lines, was not the finessed, definitive piece I’d hoped for. The origins of this book go back to the realization that I owed it to myself and, more importantly, to Brubeck to write something more permanent and fitting.

…..Most of the interview material was collected on the road in 2003, but this book also draws on face-to-face interviews recorded after that date, and occasional e-mail supplements routed through Iola’s AOL account. Brubeck was, typically, very generous with his time and willing to talk, but at the age of eighty-two, his memory was fallible, especially regarding dates and names. Some things he reported as fact were directly contradicted by my subsequent research, and all such occasions are highlighted in the text. Brubeck also had a tendency—like many musicians I’ve interviewed—to repeat a settled account of a story that, as he told it yet again, wandered further and further from reality. I learned quickly to nudge him in another direction when I’d heard the answers before. Sometimes he held back information to protect former associates and side- men who were still living in 2003—in one such case, I was only able to piece together the full story of why his bass player and drummer both quit suddenly at the end of 1953 by reading through his later correspondence. But almost everything he told me about the making of Time Out was undermined by one troubling inconsistency that, with access to other sources and the rehearsal tapes, I have done my best to iron out.

…..One sure way I found to keep Brubeck’s interest engaged was to pose questions about less-often-discussed areas of his career, and that strategy threw up some remarkable details about his friendship with Charlie Parker. Brubeck was born in California in 1920; I was born in the north of England in 1972, and that Brubeck had so much to tell me about a time and place so far outside of my own experience became intoxicating. As he talked in 2003 about segregation in the mid-1960s— and especially about how the quartet defied the Ku Klux Klan during a now-notorious concert in Alabama in 1964—the thought that such an event had taken place only eight years before I was born haunted me. As I wrote all these years later, that Brubeck’s accounts of his country’s gravest shame should have such damning relevance to Trump’s America felt unbearably poignant and tragic—time overlaps, but it is also cyclic.

…..The origins of this book are traceable to 2003, but the origins of my relationship with Brubeck’s music stretch back much further. At Newcastle City Hall, in the early 1960s, had Brubeck turned around to look at the seats that were arranged onstage to accommodate a capacity crowd, he might have looked directly into the eyes of his future biographer’s father. Later my father, who is a painter, worked on his canvases every night with Time Out on his turntable. I can remember, at the age of six or seven, keeping myself awake to hear “Blue Rondo à la Turk,” the sound of which enthralled me; family mythology insists that I would run into his studio cheering whenever it was played. In the summer of 1986, during a family holiday to Spain, I found a cassette of Brubeck’s 1973 album We’re All Together Again for the First Time in a record shop in Figueres following a visit to the Dalí Theatre-Museum. As we drove out of the city in the scorching Mediterranean sun, with the tape pumping through the rental car, threatening to blow the doors off, my mother shifted uncomfortably in the backseat next to my younger sister as the opening track, “Truth,” unfolded. This was Brubeck at his wildest, vaulting free-form clusters around the keyboard before entering into a gladiatorial dialogue with drummer Alan Dawson. Once again, I was captivated.

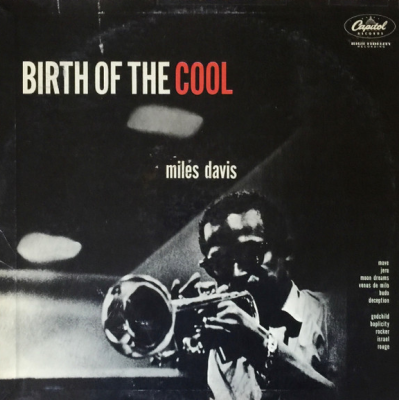

…..Everything I have achieved in my life as a musician and as a writer began with those two experiences. “Blue Rondo à la Turk” led me to more Brubeck, then to Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman, and John Coltrane (and back in history to Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton). And after I played it for my music teacher, John Hastie, “Truth” spun me in a whole other direction. If you like this, he suggested, you might well appreciate Béla Bartók’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion. A trip to the local library unearthed a long-unborrowed boxed set in which the Bartókpiece was paired with music by Karlheinz Stockhausen. I was immediately hooked, and I returned a few days later to borrow LPs of music by Pierre Boulez, Charles Ives, and Krzysztof Penderecki.

…..I met Brubeck for the first time in October 1992, when I was a music student and, following a quartet concert in Manchester, he graciously agreed to look through a piano composition I’d written called Thelonious Dreaming. Iola took me backstage and Dave played some of my harmonies through on the piano, and then he suggested we ought to keep in touch. The next time I had some music ready, I sent it to his address in Wilton, Connecticut, and was amazed when, only a week later, a reply arrived. When I was looking for employment in 1998, I pitched an interview with Brubeck to the editor of the now- defunct Classic CD magazine; the Brubeck Quartet was touring the UK, and to this day, I remain convinced that the editor muddled my name with some proper journalist who knew what they were doing. But no matter. The article, my first paid piece of journalism, was duly published in the February 1999 issue, and from that point every magazine and newspaper I’ve written for—Jazz Review, the Wire, Gramophone, Classic FM, International Piano, Choir and Organ, Jazzwise, The Guardian, and the Financial Times—seemingly had cause to commission a Brubeck article. Not writing a Brubeck book was becoming a big problem for me, and after writing the program booklet for Brubeck’s eighty-fifth birthday concerts with the London Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican Centre in 2005, I intimated to Dave, in the greenroom, that I ought to write a book. “Well . . . we’ll talk.” He smiled. Two or three attempts to write a Brubeck biography then went nowhere, and it was only after the title A Life in Time popped into my head—in a supermarket in East Finchley, North London—that everything fell into place.

…..A long personal digression, I know, but one that I hope helps explain the book that A Life in Time has ultimately become. Having gone to so much effort to place Brubeck’s life within his time, lifting him out of his time became important as I was nearing the end of the book. There was nothing to be gained by abandoning Brubeck in the 1950s and ’60s. Too many critical perspectives on Brubeck’s work, I felt, lacked credibility and were ill informed because they tapered off post-1967, when the classic quartet, featuring alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, dis- banded. Another critical cliché—the crazy number of records Brubeck sold was directly out of proportion to his influence— also struck me as suspect. True enough, the lineage of influence that led from Art Tatum to Matthew Shipp, via Thelonious Monk and Cecil Taylor—or from Miles Davis to Wadada Leo Smith, Wallace Roney, and every other trumpeter who followed him—did not apply to Brubeck. In that sense, the naysayers were right: there was/is no school of Brubeck. But being the sort of music fan who had discovered the joys of both Benny Goodman and Iannis Xenakis through Brubeck, I couldn’t buy in to the notion that the shadow he cast began and ended with Time Out and “Take Five.” The pianist who recorded “Truth” was clearly not the commercial smooth jazz pianist of myth.

…..A knottier web of influence was at play, a view confirmed by the other music journalism I was writing. When I wrote about the British post-punk band the Stranglers in 2013, I couldn’t help but notice how deeply indebted their hit record “Golden Brown” was to “Take Five”; when I interviewed Ray Davies of the Kinks, he mentioned in passing how much he had loved the Brubeck Quartet in the 1960s; then the American composer John Adams told me something similar. When I heard Australian rock band AC/DC’s “Whole Lotta Rosie” during a taxi ride, the fuzzy guitar riff sounded oddly familiar—then I realized it was based on the title track of Brubeck’s 1962 album Countdown—Time in Outer Space.

…..These experiences, and similar ones, sent me to trace Brubeck’s influence outside jazz. Musicians as varied as Anthony Braxton, Herbie Hancock, Cecil Taylor, Chick Corea, and Keith Jarrett had gone on the record to express how important Brubeck had been at different points during their careers. But I wasn’t prepared for the much-feted pianist Andrew Hill—who recorded a strikingly radical series of albums for Blue Note, beginning in 1963 with Black Fire and Smoke Stack, with progressive thinkers like Eric Dolphy, Joe Henderson, and Sam Rivers at his side—to tell me how deeply he admired Brubeck’s pianism. And so, with my title in place, I began to write a book that threw chronology to the wind, a biography that told Brubeck’s story and investigated, as rigorously as I could, the aftermath.

…..Flip this page and you’ll find yourself in 2003: at the age of eighty-two, Brubeck still felt like such a vital creative force that I thought the dust of history could wait a while. For Brubeck, jazz was never a done deal or marooned in history. He always played music in the present tense—which is where A Life in Time begins.

.

___

.

.

Excerpted from Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time by Philip Clark. Copyright © 2020. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Used by permission.

.

.

.

…..Editor’s Note…Clark does an outstanding job analyzing Brubeck’s music while also stimulating interest in revisiting recordings that are either long forgotten or previously undervalued. Much time is spent listening to Brubeck music while reading this book.

….. “Nomad” from Jazz Impressions of Eurasia (1958) is one example, which is described by Clark as a piece that was “inspired by the sight of nomadic Turks riding through Kabul on camels, playing string drums to scare off feral dogs.”

.

.

.

.