.

.

“Blue Boy and the Flattened Third,” a story by Carsten ten Brink, was a short-listed entry in our recently concluded 59th Short Fiction Contest, and is published with the consent of the author

.

.

___

.

.

.

.

Blue Boy and the Flattened Third

by Carsten ten Brink

.

…..The wind sandpapered John’s cheeks the instant he opened the swing door. By the time he’d stepped down from Bill’s Billiards into the street he was shivering.

…..He hadn’t been good on stage: every second tune had reminded him of Riley, the turd.

…..There was no traffic and even the pizza place had closed, and he missed its earlier smells of warm mozzarella and meat. The chill air did, however, carry the hint of something, a snatch of melody from a passing car or a distant open window, and he listened, seeking its source.

…..He pulled up the collar of his coat and tugged at his trilby, making sure it was wedged firmly. A metallic rattle came from his backpack when he lowered his hand from the hat: he knew the sound – a case must have opened and one of the harrys was loose. Given how his day had been, he’d probably damage it. And there was little he enjoyed less than spending a morning on harmonica repairs. He thought about the effort involved in taking off the pack, which was jammed with mikes and harrys, and digging around in it to secure the instrument. He’d have to take off his gloves and work the clasps barehanded and that damned wind had crossed the lake from the freezing north a thousand miles away. No, he’d just walk carefully, and try not to bash the instrument.

…..A thousand miles away? Wind across the lake? There was something there, a song title, or at least a line. The “freezing thousand”? The “frozen thousand”? He repeated “frozen thousand” to himself, to remember it for later, when he could write it down. Here in the open his fingers would freeze before he’d written a word. Hm, another idea: “Frozen fingers, frozen lips”… Maybe force that into an upbeat ending, or finish up with one more song of death and loss?

…..There were more important things to think about, stuff that he’d almost managed to suppress during his performance on stage at Bill’s: he’d have to do something now about the nickname, come up with a memorable one, a name as good as the one he’d really wanted. And then get the others to support it, push it hard in the music press and scrawl it on all the posters. John “Yelping” Smith had started as a joke; no-one would take him seriously with that name, even if he now played his favourite arpeggio combos with a dynamic that was yelp-like – and was getting known for it. But that had been a place-holder, nothing more.

…..Years of planning. If not for Riley. He’d have to do something about Riley as well.

.

…..His coat collar had slipped down again. He wished he’d thought of earmuffs but didn’t like wearing them at the best of times, the way they dulled the sounds of the street. Sounds were his thing. They inspired him. The rat-tat-tats of the overhead train and the hydraulic hisses of a bus as much part of some of his tunes as the chugging of steam trains had been for the greats. Sounds John could make sexy, mournful or threatening, as he pleased. Ta-hooka-ta-hooka-ta-hooka, in and out, in and out, he puffed as he walked, in time with his steps. He’d learned that one as a boy. From watching Blue Boy Smith. It was all about Blue Boy Smith. His entire life from that TV show on.

…..That turd, Riley.

.

…..Ta-hooka-ta-hooka-ta-hooka. He repeated it, moving his feet in the rhythm, until his breath changed and his anger faded. Buddhists had their mantras; he had scales and licks, most borrowed from a Blue Boy.

…..Blue Boy Smith. The first one had been a genius with a harry, even though his toothless grin and lazy eye had fooled many into thinking he was dumb. John had read about him, not that there had been much on the first Blue Boy – he’d died under Eisenhower – but Blue Boy had learned some theory, talked in an interview about chords and arpeggios and scales and modes. Not just in the vernacular of his harmonica peers, of straight and crossed instruments, of positions, of call and response. Blue Boy had known it all.

…..John’s toe-capped feet now click-clacked Boom-bah-boomm-beh-boomm as he walked, in the lick Blue Boy had made famous. As he passed the Goodwill store, its steel shutters up for the night, he heard the store’s metal slats rattling from the wind, in a rhythm that almost echoed his footsteps.

…..He started a little jig, to test the echo, but while dancing he thought of Riley again. He brought his shoe down hard onto the paving stone and imagined Riley’s head squashed under it. He twisted his foot, Shave-and-a-haircut-TWO-BITS, pushed hardest in the last phrase and then drew his foot along the floor, scraping Riley off the sole.

.

…..The lights were red at the crossing but there was no traffic, and he was tempted. But this was bar-town, and Saturday night: every second driver would be a beer and a boilermaker or two into DUI-ville. With the weight of the mikes and harrys on his back he couldn’t move as fast as he’d like. He’d wait. And think of what he really could do about, or to, Riley. He’d been patient last time, but with Riley he didn’t have that luxury. Or was it already too late?

.

…..From the road ahead he heard music again, several notes, some carrying better, more clearly than others. And his ears weren’t just good, he damned near had perfect pitch, even if in recent months he’d sometimes struggled to work out where the sounds had come from. The lights changed and he stepped into the street, his pace slow to reduce the sound of his footsteps. He listened: there was a C and an F and then a long, triste G♭ and an F again, an angry one this time, and then a pair of triplets too fast and too slurred to identify entirely before the sounds trailed away. And too many notes missing for him to guess the melody, but the scale was probably a minor blues.

…..Several steps later he heard a single note, a distinct E♭, rising and falling, a clarion call of pained surprise. Others couldn’t always hear the emotion in the notes like he could, couldn’t project it either when they played. The first Blue Boy had been able to, no question.

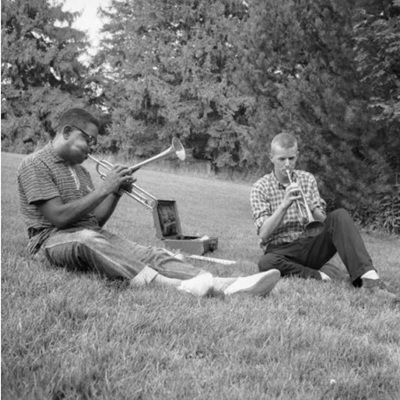

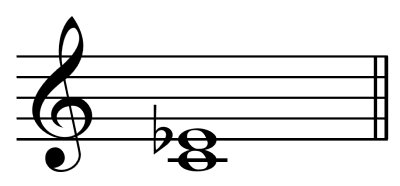

…..The second Blue Boy had been a great too, and John’s real inspiration. Blue Boy had been on TV, a birthday special in black-and-white, sweaty forehead and as toothless as his predecessor. And he’d played, how he’d played. In first position he’d made the flattened third sound as clear as a bell, something few could do, the reason most played in second, not that John had understood that, not at that time, when he’d simply wanted to make the instrument he’d got for his birthday copy the sounds he’d just heard on TV. Blue Boy’s harrys were the gymnasts and contortionists of the blues scene, but somehow, whenever someone would interview him, ask him about his music, he’d be monosyllabic, as if he’d not understood the question. They’d joked that Blue Boy had traded his brains and his teeth with the Tooth Fairy for talent, but that was nonsense. If Blue Boy Two had traded for talent, it had been his soul he’d offered to the Devil, just like Robert Johnson had bargained at the Crossroads to get his magic fingers. Only the Devil could hear the Blues, that’s what they said.

…..Not that he took such stuff seriously.

…..Blue Boy Two hadn’t even been born a Smith; nor had he been related to Blue Boy. He hadn’t even played like him. But he’d seen the angle, heard the temptation in the radio stations playing Blue Boy Smith greats, and had changed his name. He’d re-released his own old material under his new name, added cover versions of original Blue Boy tracks and sold, sold, sold. To this day most listeners didn’t know that there’d been more than one Blue Boy. Even those that did had forgotten that Blue Boy Two had once been Dark Lemon Cotton, maybe technically better than his predecessor, but a musician who until then had never had a hit, never sold out a venue larger than the back room of a pool hall. Like Bill’s Billiards, where he’d had his first monthly gig as Dark Lemon, and then had come back as the famous Blue Boy, a dozen times a year, to play a set or to drink a beer, with only Bill knowing when he’d show up. Bill would tell his regulars, those that liked the music and could be trusted to slip a banknote or two into the hat at the end. That of course had sometimes included John. Blue Boy had let John join him in a jam once, but only once. Apparently Blue Boy hadn’t enjoyed jamming as he got older; at least that was what Bill had told John when he asked if he could jam with the legend again. But Blue Boy had jammed sometimes, across town, with that turd Riley. Blue Boy had liked Riley.

.

…..A gust of wind rushed into John’s face and he felt his trilby threatened. He grabbed for it, the brass button on the brim frost to his fingers, making him think for an instant of snow-covered corpses. Once again behind him he heard the warning rattle of a harry and then a dull scrape, like the scuffing sound of his steel-tipped shoe on paving stone, as the metal instrument scratched at one of his mikes. A trilby in this windy city: on nights like this he had to question his choice. He rubbed one exposed ear, then the other. This was the place for wool that warmed and not of trilby brims that caught every breeze. But, hey, a blues musician, one who knew the signature hat Blue Boys One and Two had preferred, a musician who wore it every time he played a hall or a pool bar, especially Bill’s, and every time he walked home from a gig, a musician looking to be recognised, just in case someone wanted to buy one of the recordings in the backpack or offer him a mike and a stage, yes, that musician would wear a trilby with a brass button. He’d take it off when the bus arrived, unless someone from Bill’s boarded with him, but the streets were empty, most drinkers gone before he’d even finished his last set. Yeah, put on the wool beanie once inside and seated. Reorganise the backpack too and restrain that rebellious harry.

…..Hm, ‘Restrain the Rebel’… another song idea perhaps for the notebook in his pack? Walking alone after a drink always gave him ideas and lyrics took his mind off things.

…..At the boarded-up windows of Superior Chicken the wind fell silent and it was easier to concentrate. He’d just found a great chorus – “Restrain the Rebel, Tie the Rebel Down!” – with the option of switching the second “rebel” with a range of rude words to suit the audience. He smiled at the thought of a crowd shouting the chorus back at him. The melody needed work but that could wait. Walking was for finding lyrics, unearthing them from their hiding places where they’d been waiting for a song. He’d written a lot of songs lately about regret and guilt, of death and of murder, real blues songs, but this one had energy, anger even, if he wanted it. Anger because of what Riley had done.

…..The song shouldn’t really be about Riley – but he could use the anger and the surprise. And he realised, as he played with lyrics, that some of the anger was self-directed, because he should have seen Riley coming and acted first.

…..He was rehearsing another pair of verses – “I Ain’t Sorry, For What I’m Gonna Do” – when, stepping alongside the barred windows of neon-framed Petrov’s Pawnshop, he heard music again, penetrating single tones, but black keys this time, and blue notes, B♭’s mostly. And then, just as he passed the door of Lakes Funerals, he heard a triplet of E♭’s, Boo-boo-boo supernaturally fast and crisp, the flattened third almost impossible to play on that harry. With those three notes the sound stopped. He was alone in the silent cold.

…..He was hearing things again: E♭’s had been calling out without warning and disappearing for two years. Always reminding him. Even car horns seemed to have been re-tuned to an E♭.

…..He lengthened his stride. This time the harry on his back was mute, no more a distraction from the night’s sounds. What had those verses been again? Something about being sorry, but not regretful? The words had fled, back into hiding, and now he was struggling, failing, to remember them. An image of Blue Boy Two came instead, from that old TV show, the musician swaying on a stool as he played.

…..John stomped his feet and clapped his hands together, and then shook them. Damn this cold.

…..A block ahead, briefly caught in the light, was the deserted bus stop. Its fingerpost pole held only two signs, a sombre 1188 pointing out into the street and a rusted-red “Nick’s” in, toward the dark empty lot. The pole and its arms made a thin crucifix that swayed in silhouette under the winking red taillights of a departing car.

…..Some bluesmen die young, like Robert Johnson had, no doubt pleasing the Devil, who got the guitarist’s soul early; others play well beyond their twilight years, arthritic fingers still accurate on slow songs and aging lungs aided by microphones, and Blue Boy Two, despite his love of whisky – immortalised in his classic Dropped Bottle Blues – had been one of them. He’d stubbornly refused to die. He’d ceased recording but had never retired, occasionally on stage as the guest of someone younger and famous, and keen to associate themselves with a legendary Blue Boy. His name had continued to have value, a value that John had dreamed of.

…..John was a Smith, after all, and almost twenty years ago, when Blue Boy Two had been sixty, and John still boyish, he’d dedicated himself to learning the tunes. He’d mastered most of them, played them in tribute evenings and at festivals, worn the trilby and he had waited, and waited, for Blue Boy’s final flattened third. He’d worn out dozens of harrys practising, waiting for Blue Boy.

…..The tunes he’d struggled with had involved the harry’s hidden notes, the ones the instrument wasn’t designed to play but which could be coaxed out of hiding. Some were easy to find but others, especially Blue Boy’s signature E♭ in first position, resisted even the best musicians. If John contorted his mouth and raised his tongue, and played very quickly, skidded over the note, he got away with it, but it was never enough to play the drawn-out notes of Blue Gravestone. How long he’d practised. Yes, he could play the tune for an audience, he’d done so that very night, but only on the harry he’d customised specifically for that song, its reeds changed to fit.

…..Riley.

…..He had to give Riley credit – the turd could handle Blue Gravestone, and on an unadjusted harry; he’d heard him play it often enough – but at least Riley struggled with the faster Blue Boy tracks, stumbled badly over the notes, and now in his live sets only played Blue Boy’s slow tunes. That was something Riley couldn’t fix with a retuned harry, no matter how hard he tried. The turd didn’t even seem to know much about the workings of a harmonica, and probably had no clue that John used what he’d called his Gravestone Special. No way would John ever advertise his customised harry, expose himself to comments about his ability and to comparisons with other musicians, especially comparisons with Riley, not as long as he had his dream. He reached into the inside pocket of his jacket where he kept his two favourite harrys, and his fingers found the Gravestone Special’s raised-bump profile, so easy to identify even on the darkest stage. He held it to his mouth and began to play.

…..The tune wasn’t Blue Gravestone but one he’d written himself – well, almost written: the ending still didn’t work. 1188 Blues, he called it. It was a tribute to Blue Boy but faster, the underlying dynamic that of the chug and chuttle of the 1188 bus. He played the key lick, once, twice, and then improvised, hoping for inspiration. He only had three weeks left before the event, a concert to mark what would have been Blue Boy Two’s 80th birthday. He planned to launch the song there.

…..And launch himself too, or so he’d hoped, as Blue Boy Smith the Third.

…..But the turd Riley had beaten him to it. That very morning, with a press release “in memory of his tragic death two years ago,” Riley had announced the change of his name, a full legal change even, covering all the bases, to Blue Boy Smith.

…..That should have been John’s name. He was a Smith and he played Blue Boy’s music far better than Riley did. He’d deserved to be the third Blue Boy and he had…

…..If there was a Devil he’d be on his throne right now laughing at John and his dream.

…..Something not to think about. He played four bars of melody from 1188 Blues, and then reversed the order of the notes. A long, drawn-out F sounded breathy and uneven. He tapped the Gravestone Special on his thigh to free any pocket lint or saliva from the reeds and played the note again.

…..An echoing E♭ came from the street ahead and the fingerpost pole, now only yards away, appeared to hum.

…..1188 Blues. Might it be too direct, naming a song after the bus that had… and he remembered the scene, Blue Boy Two’s leather bandolier of harrys torn, the instruments skittering on the snowy road, the bus doors opening with a hydraulic exhale and a creak. Maybe the song could refer to the bus indirectly, but not in the title.

…..He drew a set of low notes through the harry. Again a sound from the street but this time his call’s response was definitely not an echo, the first notes an octave too high before they returned to a mournful set of the inevitable E♭s, paced like a march, Boom-boom-boom-bam-boomboom-boomboom-boomboom. He turned. No one there. He walked on, shook his head free of the sounds and wondered if he’d simply imagined it.

…..Then another sound – a chug and a chuttle – and he turned.

…..The bus appeared behind him. He felt a push, and a weight on his chest as if he were wearing a bandolier of leaden harrys even heavier than the pack on his back, and he stumbled, just as Blue Boy had done. As he fell, he heard again the march of the flattened thirds, and knew how the song should end.

.

.

___

.

.

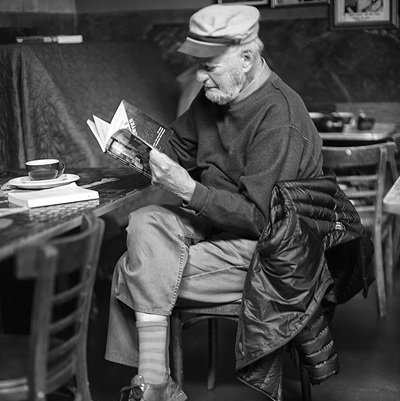

photo by S. Haque-Everding

Carsten ten Brink is a writer, photographer and artist based in London, England. He is currently editing two completed novels and assembling a collection of short stories, when he isn’t distracted by travel or a new story to tell. After spending most of the last decade working on novels, since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic ten Brink has dedicated more time to short story projects. Short fiction has appeared in Between The Lines, Congeries and Morley Muse. His photographs have appeared in publications around the world and have been viewed in excess of 25 million times. A lover of blues and world music, he has been studying the diatonic harmonica for almost a decade.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read “His Second Instrument,” by Dave Wakely, the winning story in the 59th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Click here to read “Mouth Organ” by Emily Jon Tobias, the winning story in the 58th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Click here to read “Thunder,” a short story by Robert Knox

Click here to read “High John Saw the Holy Number” a short story by Con Chapman

Click here for information about the upcoming Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

.

.

.