.

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

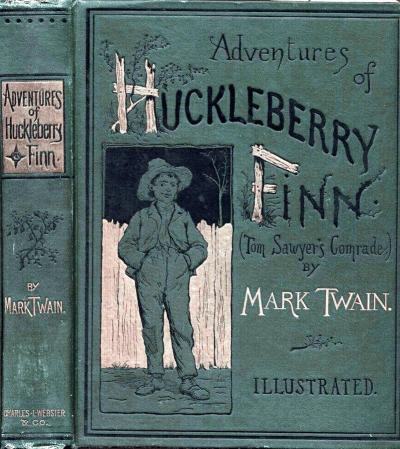

The cover of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the second (first US-published) 1885 edition of the book

.

___

.

…..James Henry Harris wrote a book with a confronting title; N: My Encounter with Racism and the Forbidden Word in an American Classic. “N,” of course, is the “forbidden word.” Harris wants white people to never use it. Here I am, a white person, looking at the word, reviewing a memoir about its use in an American classic, Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and its passive use by white grad students in a college classroom that is a former slaveowner’s quarters. Harris reveals, in the situation, a totally unique perspective with all its complexity — ‘do gooder’ whites (reviewer, reader, students and instructor) convened to discuss the cultural value of a classic in an age of relativity. The students, aided by the opinion of Toni Morrison, want to hear the use of Twain’s “forbidden word” as a condition of the author’s time, but Harris shows how he was let off too easily, and how the word still offends. No relativity granted. It’s a perfect learning moment for critical race theory (CRT).

…..Jerry Jazz Musician recently published my review of that book (available to read by clicking here), and followed that up with a conversation with Professor Harris about his work – particularly Black Suffering and N – on June 29, 2022. The edited version of that exchange follows. (previously published in Counterpoint)

-John Hawkins

.

.

___

.

.

photo via Virginia Union University

Reverend Dr. James Henry Harris is Distinguished Professor of Homiletics and Pastoral Theology and a research scholar in religion and humanities at the Samuel DeWitt Proctor School of Theology, Virginia Union University. He also serves as chair of the theology faculty and pastor of Second Baptist Church, Richmond, Virginia. He is a former president of the Academy of Homiletics and recipient of the Henry Luce Fellowship in Theology. He is the author of numerous books, including Beyond the Tyranny of the Text and Black Suffering: Silent Pain, Hidden Hope (Fortress Press, 2020). His latest book is N: My Encounter with Racism and the Forbidden Word in an American Classic, a memoir that describes and critically wonders about a graduate English class he took on Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, and provides crucial insight into the critical race theory conundrum.

.

.

John Kendall Hawkins is an American freelance writer currently residing in Australia. His poetry, commentary and reviews have appeared in publications in Oceania, Europe, and the US. He is a regular contributor to Counterpunch magazine. He is a former winner of the Academy of American Poets prize, and is currently working on a novel.

.

.

___

.

.

Black Sufferance / Insufferable Whites: A Conversation with Reverend Dr. James Henry Harris

by John Kendall Hawkins

.

John Hawkins:

In Native Son (1940), Richard Wright observed of white people: “To Bigger and his kind, white people were not really people; they were a sort of great natural force, like a stormy sky looming overhead or like a deep swirling river stretching suddenly at one’s feet in the dark.” This is great writing and probably gives too much credit to whites. But it did have me thinking that this “natural force” that Wright refers to has been responsible for leading the planet to climate catastrophe and, maybe, species extinction. And we can go to Derek Chauvin, as a force, you know, the knee in the neck guy.

James Henry Harris:

Yes. George Floyd went into a grocery store in Middle America to purchase some cigarettes, purportedly with a counterfeit $20 bill, and is literally unable to leave that store without losing his life. It’s almost incomprehensible.

I’ve always been fascinated with Richard Wright and some of the Harlem Renaissance writers. I had no interest in some of the things we were reading in high school English classes, you know, like Beowulf and other pieces. And then when the teacher assigned Black Boy, it just spoke to my soul.

Almost unconsciously my writing has been influenced by people like Richard Wright and James Baldwin and maybe even Countee Cullen as well. I adored reading their works, and some element kind of comes through in my own writing and some of the same issues that existed, you know, the issues of race and so forth that Bigger Thomas encountered. And what Wright talked about, I mean, it’s almost like it’s not yesterday, but today.

When I read the Wright quote, I think of Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, who wrote, “Black people love white people. And white people struggle to be human.” And in a very real sense, I was thinking that it’s almost like a straight line. I argue in my book Black Suffering that there is a straight line between American chattel slavery and what goes on today. The death of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and all of these things, that it’s almost a straight line. And it continues today with the election of the last president. And so when I read that Wright quote, it just seems to be so accurate, in terms of what is going on today. You know, we see the bubbling over of white people’s apparent concern about the browning of America. And overturning Roe versus Wade. I think that is a part of a larger goal to try to halt what I’m calling the browning of America.

Hawkins:

I grew up in the 1960’s, so I have a pretty good sense of how revolutionary it was back then, in terms of activism. People wanted change and wanted the war to stop. Children who couldn’t vote were being drafted and sent to war against their will. They can’t vote, but they can go die for us, you know, and they had no say at all. They’re basically slaves really being sent to war, whether they liked it or not. But there was drama, there was fight back, the Black Panthers were saying, No, it’s not okay. Angela Davis said, No, it’s not okay. And there was just a more dynamic sense of an urgency to actually get things done. It seems to have died a little bit.

Harris:

I think you’re absolutely right. And the complexity of it now has it grounded in the farcical notion of integration. You’re talking about the ’60’s. Segregation was the dominant practice. It was codified in the law, which made it much more of a bifurcated thing that was easier to deal with then – up until the recent [Trump] administration, where there was a kind of sleepiness about race relations in America. As a matter of fact, some African Americans, you know, young people, who are millennials, and others, have said to me things like, you know, well, that was in your generation. We don’t have that problem today. And so forth. And then comes Obama, which, for a week or two, kind of substantiated those views.

Hawkins:

Speaking of complexity, let’s talk about your memoir, N: My Encounter with Racism and the Forbidden Word in an American Classic. That classic being Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. One thing you say in your book is that no white person has the right to use “N-word.” I was marveling, as a white reviewer, at the task of reading your book in which the “N-word” features so much, even in the contention of its use. Should I even be reading your book? The title is forbidding. And confrontational in a way. Reminded me a bit of the time as a youngster when I saw Abbie Hoffman’s book in a store and was going to buy it, but got caught up in the title of the book: Steal This Book. Moral dilemma time, in an arch way.

But it must have been a strange moral dilemma for you as well, entering a college classroom to sit with white people and their white instructor to discuss Huckleberry Finn and hear your fellow students use the “Forbidden Word” -because it’s part of the narrative of Twain’s book, 222 times – and feel violated by the word spoken out, while knowing that it would be again forbidden outside, when the class was finished, and re-enter the world of political correctness. Strange. It was a welcome experience for this reader when you confronted that anomaly immediately.

Harris:

What? White America, you know, made The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn a national and international bestseller. And it blatantly used the word, as I said. You know, hundreds of times. And these same people are now saying they have a problem with the word.

Hawkins:

It’s strange. There’s a lot of delicacy around handling the race question from a white point of view, as if we don’t have an effective way of addressing it. We’re creating a barrier, you know, and I’m just trying to figure out the politics of how we went from Dick Gregory using “Nigger” as his book’s title, and right on its cover. That’s the name of the book versus what you’re doing, with N., which is like drawing attention to the changes that have taken place politically over the last 50 years, since Gregory’s book came out.

Harris:

Yeah. Well, you know, in his 2002 book, the Harvard Law Professor Randall Kennedy also uses the word in the book’s title.

It’s a dialectic, in a sense. I mean, Trump’s views are rather racist, front and center. And he has all of these people joining him. That’s on the one hand. And then on the other hand, you have other people, maybe liberals or quasi- radicals on the left who feel some kind of conflict with the discussion of rights. But, you know, that as a Black person, you cannot walk out the door without being encountered with the issue of race in one form or another.

I’ve thought about these things a lot. I’ve spent a lot of time in my life studying philosophy. And whites study Hegel and Plato and Aristotle and all of these other people. And, you know, the problem I have is that whites understand everything from physics to calculus to biochemistry and to philosophy, and to argue all of a sudden that there’s something that they don’t understand is amazing to me. It’s not even true. I’m saying it’s basically a lie. I just don’t buy it.

Hawkins:

Well, can whites effectively teach Critical Race Theory? When I think of CRT being introduced it reminds me of some of my undergraduate English Lit classes at UMass-Boston which were taught by a new wave of Harvard-trained professors. They brought into the classroom active feminist approaches to lit that seemed, at that time, condescending in the re-tooling of the white working class minds they presumed needed a healthy dose of critical feminine theory to show how unreconstructed their plantation thoughts were regarding women in fiction. I admit, I resented the presumptuousness that I felt came out of her class superiority – like I was some MAGA pleb – teaching at me, rather than with me. I mean, hell, I was a lefty! A lot of the classes seemed like that back then – when radical chic meant radical chick with radical cheek – taught by Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Angela Davis or Billie Jean King, who looked as if she’d hop right over the table like Professor Turgeson in Rodney Dangerfield’s Back to School and come at you if you said the wrong thing. It confronted the ego. But I came away with a healthy appreciation of reader-response theory, so maybe CRT needs a similar break in period?

Harris:

I graduated from the University of Virginia, where the air of gentility is in the air everywhere. And yet, Jefferson was a slave owner. And a slave trader. And as a graduate student at the University of Virginia, I would make people very uncomfortable talking about these things in class, because I don’t know if you’ve ever been to the UVA campus, but there are multiple statues of Jefferson on campus, and there are still some renovated slave quarters that also operate as classrooms in certain areas. So, I bring this up to point out that there is a kind of ingrained, insidious kind of duplicity that pervades American society and culture. To overcome that is to overcome something so embedded in American history and in the American psyche.

And this whole issue of denial, which is so present in the pushback against critical race theory. And maybe any critical theory, I was thinking, but definitely critical race theory. It’s like the history of American racism has been so fabricated and fictionalized that it has almost become truth to some people. I was born in the 1950’s and grew up, basically, in the ’60’s. And when I was studying Virginia history and American history, it was advanced that slaves were happy, and almost grateful for the way they were treated by the slave master. I mean, a lot of these narratives were actually placed in American history books. Critical race theory only seeks to point out historical truths as the pushback to that. So there is no real interest in the truth.

Hawkins:

Yeah. N: My Encounter with Racism and the Forbidden Word in an American Classic, your account of taking a graduate course in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, including the setting of the classroom in an old plantation, speaks to that “insidious duplicity” quite eloquently in one passage. You write:

“This is where Black folk learned the ways of white folk. This is where Black folk acquired the necessary astuteness to speak, breathe, and exist without the Otherness that defined them… It is where the practices of smiling, ‘softshoeing,’ and ‘cooning’ were refined into a tradition of degradation and self-deprecation. This is the house in which Blacks learned to wear masks and store their anger in their hearts and souls until it could be unleashed like hellfire and brimstone.” Sounds very surreal and disturbing.

I know what you mean when you say it could be any critical theory that causes problems for the collective delusion. Recently, I did a review of a critical analysis of Robinson Crusoe, which is, in America, regarded as a tale of the rugged individualist. But re-reading it, you remember the guy was a slave who escaped from Africa and sold his mate to the Portuguese, and then finds fortune with tobacco farming in South America. Not satisfied, he rounds up other farmers and sets out to Africa to buy slaves – which is when the fully-laden ship goes down, with the Crusoe the lone survivor. On the “desert” island are all kinds of wildlife, he sets up three abodes, and salvages virtually the entire store of goods from the reefed ship. He lived in luxury and without much need for ruggedness. When Friday arrives, 30 years later, Crusoe’s first impulse is to enslave him. We know that not much rehabilitation has been afforded the tale because Tom Hanks gave us the latest white boy update of rugged individualism in the 2000 film Castaway, where he had to make do with freight of goodies from a crashed DHL plane.

Harris:

Absolutely. But part of my argument is that, you know, this is normative. And I’m saying to some degree that normativity was, in my view, advanced by Mark Twain and his use of the “N-word.” You normalize the use of the word and put it front and center in the public domain. So, I’m saying that America is very adept at this, and lots of days I can only scratch my head. It’s like walking up against a brick wall almost daily.

Hawkins:

So, you wouldn’t ban Huckleberry Finn, but as far as teaching it, you make the fair point that it really requires a mature mind; a mind that’s been through some critical analysis of itself to actually know how to teach it. So where do you draw the balance between a book filled with so many forbidden word references? Should it only be taught under certain circumstances – like someone who actually can teach it rather than generally assigned? Like, how do we figure out who can actually teach it without doing damage?

Harris:

As an aside, my best friend in that Huck Finn class was a white man who had also graduated from the University of Virginia. He was a history major before he began to focus on literature and writing. So, someone like him is clearly qualified, and there are many others. The main thing is to have some degree of sensitivity to what’s really going on in the book. It is complex for sure. I intentionally got into that class because the book’s presence has been so ubiquitous in American literature, and I didn’t want to get my master’s degree in English literature without having read the purported classics.

Hawkins:

Toni Morrison defends Twain’s use of the “forbidden word” in his work, especially Huck Finn, and writes:

“In the early eighties, I read Huckleberry Finn again, provoked, I believe, by demands to remove the novel from the libraries and required reading lists of public schools. These efforts were based, it seemed to me, on a narrow notion of how to handle the offense. Mark Twain’s use of the term “[n–]” would occasion for black students and the corrosive effect it would have on white ones. It struck me as a purist yet elementary kind of censorship designed to appease adults rather than educate children. Amputate the problem, band-aid the solution.” Do you agree?

Harris:

This is a bit complicated because I think white America prefers hearing from Blacks they have endorsed in some way. And so I think being a professor at Princeton like Toni Morrison or at Harvard like Randall Kennedy at Harvard somehow makes it seem as if they are the spokespeople for their race. The problem I have with that is that they don’t even teach at a Black university, like I do, and have for most of my academic life. So I’m trying to answer the question: How do they become more of an authority on blackness and Black education?

Hawkins:

You draw the conclusion by the end of the class that “Mark Twain was a racist.” Can you say more on this?

Harris:

I was the only Black male in the class, and the only person in the class who had been called the “N-word.” So I had a deeper understanding than anybody else in the class about this topic. Because Toni Morrison is such a prominent name, many people in the world of letters probably just took her word for Twain’s value. But I wasn’t thinking along those lines at all in terms of Toni Morrison’s thought. I think that Twain did do a lot of things, and was probably very amenable to Blacks, but I think that was normal in the world of the slaveocracy. So I just felt that the normalization of the word or the ubiquitous use of the word by Twain made him a consummate racist. I think he used the word almost without a full thought – it was just so natural. Yeah. And I think that is probably what constitutes racism.

Hawkins:

You note that the “forbidden word” occurs 220 times in the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The same word occurs in your memoir 177 times. Made me think of Miles Davis’s Tribute to Jack Johnson, a tower of strength seemingly warning the listener: “I’m Black; they’ll never let me forget it. I’m Black alright; I’ll never let them forget it.” Can we ever get over skin color as politics? Or will there always be a knee in the neck waiting?

Harris:

Martin Luther King Jr said in 1967/68 that the “stigma of color” is the source of Black pain and suffering. Fifty five years later, his words continue to ring true. There seems to be no other ethnic groups in America who bear the unique scars of American chattel slavery. Only Black folk hold this distinction and only Blacks have been treated with such sustained violence and evil. 246 years! The same age as American-independence! Sojourner Truth was right in exclaiming “what evil has this slavery not done.” So, my hope is in the language of the Negro spiritual: “I’m so glad trouble don’t last always.” Your question, will there always be a knee in the neck waiting? My simple answer is grounded in hope; however, a more pragmatic approach would have to include considering a response that is equally as violent as the knee on the necks of Blacks. In the spirit of the Old Testament: “An eye for an eye”, Or in this case, a knee for a knee.

Hawkins:

What does W.E.B. Du Bois’ term “double consciousness” mean? We know what it’s supposed to have been like in the Richard Wright era, especially with the story, “Almos’ A Man.” But when you think about it in the modern era, what is this double consciousness that he’s referring to? Where do we see it? It’s such a softball question, but…

Harris:

Well, it’s a hardball question that masquerades as a softball. But, you know, it’s complex. I both admire and not admire some of what DuBois has to say about double consciousness. It’s so much a part of Black American psychology in the sense that he’s right in talking about the two worlds and their being a part of double consciousness. And I think that it’s evident today. For example, I’ve been going to the same bank for about 20 years, and almost every time I go the teller asks for my ID. Well, she saw me last week, and the week before that and the week before that and the week before that. So, what is that? That’s a very simple example, but what is that about? I’m suggesting that it’s a minuscule example of the issues that Black people face in America daily.

So, it’s complex but there is no escaping. There’s no escaping your blackness in America. And my thinking is that the stresses that are imposed upon you contribute to all kinds of health issues, and other kinds of things where Black people are disproportionately affected by all of the major diseases – from diabetes to heart disease and so forth – and I think a lot of that is grounded in the fact that you are always subjected to a double standard. And so in some ways, your consciousness in-and-of-itself is a double consciousness.

Hawkins:

What is the way forward?

Harris:

We seem to be on a collision path toward chaos since the “Beloved Community” contemplated by Dr King is a bridge too wide and too deep to cross in this age of “turning back the clock” on civil rights, voting rights, minority rights, women’s rights, and the freedom of Black people across America. We are indeed going backwards, not forward. States Rights is a damning and evil act of regression. The Supreme Courts overturning of the landmark decision in Roe v Wade was as predictable as the weather. And, the politics of the Democrats in Congress is as sickening as the Republicans because for 50 years they did nothing to ensconce the Roe decision into law and beyond the reach of the fickleness of the Supreme Court. And now they pretend to be devastated. No reasonable human being is duped by party politics! America has been fighting the Civil War before and every year since the Emancipation Proclamation. And, it seems that the nation is poised to again spill blood in the streets over the same issue— the crucible of race.

.

.

___

.

.

.

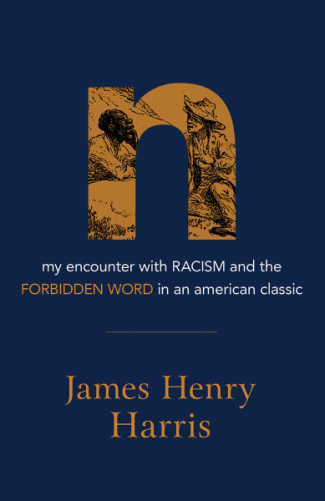

N: my encounter with RACISM and the FORBIDDEN WORD in an american classic (Fortress Press)

by James Henry Harris

.

Click here to read John Hawkins’ review of Harris’ book

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to learn how to submit your work

Click here to subscribe to the quarterly Jerry Jazz Musician newsletter

.

.

.