.

.

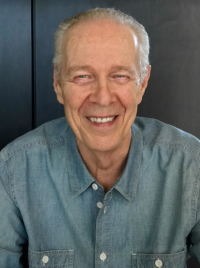

Lee Konitz (1927 – 2020) at Bach Dancing & Dynamite Society, Half Moon Bay CA

November 24, 1985

.

___

.

.

A 1985 Interview with Lee Konitz, by Bob Hecht and Grover Sales

.

…..We recently lost one of the great improvisers in jazz, alto saxophonist Lee Konitz, who died in April from complications of Covid-19, at the age of 92. Lee had been a working professional jazz musician at that point for 75 years—he was still, at 92, playing gigs internationally. His history is well-known: he had important collaborations with Lennie Tristano, the Claude Thornhill Orchestra, Stan Kenton, Miles Davis (he was a key player in the famous Birth of the Cool sessions, and with tenor man Warne Marsh. He is recognized as having been committed for all those decades to an unusually pure approach to improvisation. He once said that his way of preparing was to be as unprepared as possible! His focus was always on creating new sounds in the moment.

…..The following is a previously unpublished interview with Lee Konitz from 1985. Here is how it came about. Lee was appearing in the Bay Area, at Keystone Korner, and at the Bach Dancing & Dynamite Society in Half Moon Bay. At the time I had a video production company in San Francisco, and my friend and business partner Michael and I arranged with Lee to record a video interview during his Bay Area visit. We decided to record it at the Bach Dancing & Dynamite Society prior to his concert there, and we enlisted our friend, the late Grover Sales, the noted jazz educator and author of Jazz: America’s Classical Music, to participate in conducting the interview. Grover and I worked out in advance the subjects we wanted to ask Lee about. It was our hope at the time that the interview might be one element in a documentary project on Lee. Sadly, we were never able to get funding for that project, and nothing was ever done with the raw, unedited tapes. An initial transcript was made of the conversation, which has been in my possession all these years, though the disposition of those tapes is unknown. The following excerpts from that interview are based on that transcript. Minor editorial changes have been made to improve clarity.

.

.

___

.

.

Bob Hecht frequently contributes his essays and personal jazz stories to Jerry Jazz Musician. A veteran jazz radio broadcaster, his podcast series. The Joys of Jazz recently won international recognition from the 2019 New York Festivals Radio Awards, and can be heard at thejoysofjazz.com.

.

.

Grover Sales was a noted jazz educator and author of the popular book, .Jazz: America’s Classical Music. His long involvement in jazz included working as publicity director of the Monterey Jazz Festival for its first seven years as well as handling personal publicity for Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, and Duke Ellington. He taught jazz history at Stanford University, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and San Francisco State University.

.

.

___

.

.

photo by Fred Price

Lee Konitz, c. 1960’s

.

.

___

.

.

Listen to Lee Konitz play “All the Things You Are,” an early 1953 Pacific Jazz recording with Gerry Mulligan

.

.

___

.

.

Q: Tell us about when you first got exposed to jazz.

A: What happened was the bands, the dance bands of the thirties, were broadcasting the remotes all around the country. And I was picking up a lot of them, that’s really how it started for me. It might have been quite by accident one night I was listening to Count Basie from some place or other and that really excited me. That’s what decided that I would ask my parents for a sax.

But clarinet was my first instrument. I got a nice clarinet and a book with two hundred coupons in it and a nice teacher who kind of showed me how to play clarinet and then later the saxophone. He also taught Eddie Harris.

Q: And when did you start playing jazz professionally?

Charlie Ventura, October, 1946

.

*

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Claude Thornhill, September, 1947

A: Somewhere around the age of fifteen I was playing in cocktail lounges around Chicago without being stopped. And then I went out on the road with some bands during the war period when there was a shortage of musicians. I actually took Charlie Ventura’s place in Teddy Powell’s orchestra once in the mid-forties, and that was traumatic a little bit because I had been listening to Charlie play on the radio and I was very impressed with his ability. And when I sat down and looked at the tenor parts that he was playing with all the chord symbols written in concert, and things that I hadn’t really had experience with yet, I was a little bit taken aback, and I heard that after Teddy Powell heard my first solo, he knocked his head against the wall. (Laughter)

Q: When did you join the Claude Thornhill band?

A: That was in ‘47, I was twenty.

Q: Tell us about the Thornhill band, it was so unusual…

A: That was the most beautiful ballad band of the century, I think. Gil Evans was writing some of the arrangements, and there were two French horns and the tuba added to the conventional instrumentation, and sometimes it was just exquisite.

Q: Who else was in that band?

A: Well, Gerry Mulligan was for a while, and Red Rodney…and they were trying to make it a jazz band. Gil was dragging the band, kicking and screaming, into the twentieth century actually, teaching them, literally, physically, how to phrase bebop bass notes. I can recall that specifically, but as a balled band I think that was its forte. Claude wasn’t really a bona fide jazz player; he was a very good piano player but I never recalled him playing anything really special, just kind of conservative in a way.

Q: Now the Miles Davis nine-piece band on Capitol Records they called the “Birth of the Cool” band was an outgrowth of the Thornhill band, isn’t that true? Tell us how that happened.

A: Yes, well Miles was kind of listening to the band when we were at the Pennsylvania Hotel in New York. He would come around, and me and Gerry and Gil were very tight. For the “Birth of the Cool” band, basically the instrumentation was Gil’s idea. They used a couple of people from the Thornhill band, the tuba player, and me, and they revolved the whole thing around Miles, whose sound they liked, and who could get the gigs, too. He had already made his mark with Charlie Parker, and he was the force that they could already see was going to be important. He just had that kind of charismatic appeal already, you know, so it had to happen that way.

Q: Those recording sessions were so historic, and determined the stylistic direction of jazz, so-called cool jazz, for several years to come. Tell us about those sessions and what they were like and how you felt about playing with a group like this.

A: Well, I was more involved with Lennie Tristano at that time, so this music seemed very tame to me, I remember that distinctly. It was lovely music. I thought of it mainly as what it was, a chamber group that was mainly for writers, but with some solos to balance it. I felt that the most interesting piece in some ways, in terms of trying new techniques, was Johnny Carisi’s piece, “Israel.”

Q: Which is a blues, right?

A: Yeah, but he kind of indicated some more adventurous writing, I’d say. But all the writing on the band was beautiful and it was fun to play with it, but I didn’t take it that seriously in a way. I appreciated the music but it was really just an opportunity to play with some people and play some nice music. That was about it for me.

Q: Are you saying you had no idea when you made the Birth of the Cool sessions that they were going to be that important or that influential?

A: No, there was no thought like that at all. I didn’t think that about my work with Tristano or anything that I was doing at the time. But I felt if anything was going to make a mark it would be the Tristano situation, ‘cause we were doing some different kinds of things.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Lee Konitz and pianist Lennie Tristano on a 1956 recording of “These Foolish Things”

.

Q: So tell us about Lennie Tristano and when you joined him. He’s legendary…Please talk about the experience of studying and playing with him.

A: Well, starting from the beginning, I was playing at a ballroom with a Chicago dance band at the time, with a clarinet and a megaphone and all of that, just becoming a professional musician…and wearing brown suede shows with my tuxedo, I remember that! (Laughter) And a friend of mine, a piano player, was working across the street from the ballroom and I went there after the job to hear him and sit in, and Tristano was with the other band—which was mainly a Mexican rhumba band! And I said, ‘What is that?’ And I listened with great interest to this blind piano player really playing some interesting things on some of these rhumbas. I played a couple of tunes with that band and I remember speaking with Tristano that night, and we hit it off immediately. I needed desperately to get into the music, it was the most important thing for me at the time, yet I was just kind of listening and not yet formulating any philosophy about it. And immediately I realized how seriously he was involved in it. I became one of his students; he just had people studying with him who were interested in learning more about improvising, it wasn’t a school per se, just people studying privately. So I devoted a number of years to studying with Lennie; it was very serious study for me, and it really changed my outlook.

Lennie Tristano, August, 1947

Q: It seems that Tristano was doing some things much earlier than other musicians, like using unusual time signatures, two different times at once, and certain elements of free jazz. Were you aware at the time that this was unusual?

A: Yes, but it just felt like an outgrowth of what had been before, I think that’s the way it generally goes. He was very seriously studying Charlie Parker and was adding to that vocabulary. I mean, Charlie was playing those kinds of things, too, but Tristano went another step further with it. I was fascinated with how seriously he considered this art form you know, so I was just all ears, and ready for any suggestions that he had.

Q: It’s been said that Tristano has in a sense been inordinately influential on his students…

A: Well, there was almost a stamp that he would put on any people who stayed with him for a while. Tristano’s students, they almost walked a certain way, they looked a certain way, they played not carbon-copy style, although a lot of the people who studied with Tristano have been lumped together as all playing like Tristano. But I don’t think that’s quite as true, I think the ones who are really serious have a little bit of a slant of their own. I don’t think I play like Warne Marsh, for example, and he doesn’t play like me.

Q: Did Tristano teach you to improvise? Or can you be taught to improvise?

A: Well, he showed me how to use whatever facility I had naturally to make up variations on a given theme…it can be taught to that degree. You can’t teach someone how to feel, but you can kind of direct them to the good music to study, and to some good exercises to work out with, and I think that’s basically what he did. I hardly remember some of the things that he suggested, or it seems like nothing but mostly basic, theoretical things and kinds of exercises to play, but most of it was in the kind of sitting back and talking about art and whatever that made this very serious effect on me.

Q: What happened when you first heard Bird? Did it make an immediate impact on you?

Lester Young at New York’s Spotlite Club, c. September, 1946

A: Oh yes. I was a little bit negative as I remember. Up until that point I was really listening to Johnny Hodges and Benny Carter, and Bird’s playing was much too much for me to get at that point. So it it took me a while to get. I think chronologically I actually heard Bird before I heard Lester Young, so I had to get back a notch so to speak to lead up to that. I also had an ego problem at that time—someone wrote in a magazine that I was the only alto player who wasn’t sounding like Bird at that time, and I thought I better not listen too closely and be caught up, as is inevitable if you really listen to that music, so I really avoided it for a while. And then when I realized I was missing one of the great players, I started to listen carefully.

Q: And Lester Young has been an influence too, right?

A: I hope so, he’s one of the most beautiful improvisers in this music. Whenever I feel like listening to something very special, he might be one of the people I would listen to. It never wears off. I think that’s certainly the mark of good music.

Dave Brubeck, 1954

Q: Back to Tristano’s music for a moment…some people have pointed out the superficial similarities between his music and that of the Dave Brubeck quartet: both featured classically oriented musicians who played jazz. Why do you think one group became wildly popular with a mass public and the other is relatively unheard of except among critics, musicians and hard-core aficionados?

A: Well, my first reaction is that Brubeck’s music, with Dave dramatically hitting the instrument the way he did and all the suggestions of Wagner or whatever, it was very dramatic, you know, and Paul Desmond had that lovely, lyrical quality—it was sort of like Beauty and the Beast in some way, and it worked. Our thing just didn’t have that kind of impact, that’s all, it was just for whatever reason less communicable. One of the reasons was a certain quality we had, you know, but that’s still no excuse—it still has to come out and make some impact, and it did you know, but not that kind of impact. And we weren’t able to stay together to develop that product, so it didn’t work.

Q: As an aside, Paul Desmond used to talk to me a lot about how much he admired your playing.

A: Oh?

Q: I thought I might as well throw that in…

A: I’m glad you told me, he never told me. I can hear it but he never told me.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Lee Konitz on a 1987 recording of “Stella by Starlight”

.

Q: Let’s talk about the art of improvising. You have said you try never to play things the same way twice…

A: Or, as Shelly Manne said, a jazz musician never plays something the same way once! I would think most of us in our preparation for performing tend to want to be a little more secure, so in making a record or doing a concert one might tend to want to know beforehand what to play. But I decided, because of the way I function, that I would try to improvise each time—so this is what’s known as the blank slate approach, where you go in without any preconceived ideas. So that just keeps it interesting for me. I would certainly benefit in some ways if I were more prepared for fast tempos sometimes, but I’m getting around to it. I’m just a slow learner. I decided a long time ago that I was going to live forever, so I’m not in a hurry!

Q: Is there any special technique to get to that blank slate for you?

A: Well, it’s just sort of like a daily practice thing—I just practice improvising each day to develop that ability.

Q: In a New Yorker interview with Whitney Balliett you talked about how there are, for you, ten levels of improvisation. Would you talk about that, and how you can communicate something like this to your students?

Lee Konitz at New York’s Top of the Gate, sometime in the 1980’s

A: I was trying to figure out for myself as a player how to eliminate some of the unnecessary mystery to this process. I feel that there is a basic mystery, if you will, that makes it fascinating as a player and a listener—the element of really being able to compose on the spot. It’s magical and spiritual and all those kinds of things—that quality must be an important ingredient of course. But there’s a certain mystery that can be eliminated, and over some years of checking this out I felt that most of us, in trying to get out to a very high level of spontaneity tend to overshoot the mark by a long shot. And I thought if it were possible to describe or demonstrate in some way how one could stay closer to home base, and have some familiar area to refer to, so that we wouldn’t have to be dealing so soon, so quickly, with a totally new melody. That’s what it finally comes down to. If you’re standing up there in front of everybody and making up a totally new melody, chances are it’s not going to work; but if you could just gradually approach that totally new melody by slowly displacing part of the given materials, that possibly we could stay in control and eliminate that aspect of the mysterious part of the process.

Q: Over the years you have used, and re-used, a group of standard tunes…

A: Yes, tunes like “All the Things You Are,” “Stella by Starlight,” “I’ll Remember April,” “Body & Soul,” “Just Friends,” “Star Eyes”: those are just some of my favorite tunes: it’s just very good material melodically and harmonically, and I feel satisfied if I can play a familiar piece and bring a new variation to it.

Q: There were three movements in jazz that quickly followed the so-called cool period: the hard bop or soul/funk reaction in the middle fifties, and then modal jazz with Miles, and then Ornette Coleman. Would you talk about your experience with these successive movements, what you thought about them and if they had any impact on you, negatively or positively.

A: First of all, about that ‘cool’ label—there was always a negative connotation to it, a negative reference to a so-called dilution of mainstream jazz. But I mean all one has to do is listen to Tristano, and he’s the furthest thing from being a cool player that I can imagine. Warne Marsh and I were more restrained possibly, and that might have something to do with that kind of reaction, but Tristano was never a cool musician in that sense. He was playing as hard or harder than anybody, Good Lord, so that label always felt strange to me.

Q: And the hard bop period?

A: For me that music was not totally accessible, Horace Silver and Art Blakey and those people. I’ve felt that this was a little bit too much of an exaggeration of the expression for me. I was looking more for, not restraint but a little more gentility or whatever that would be more classical I suppose, rather than the out-and-out hard-hitting music. I’ve never had that kind of temperament or blood pressure to go along with it, so I couldn’t play it, and so I stayed away from that music for a long time. It’s just now that I’m going back to that music, and the best of that music is, I think, really good music and very classical in the sense of the best part of jazz being a classical music. That music is now in my listening cycle, and I’m glad I got to it before I go into the next lifetime.

Q: And modal music, like Miles’ Kind of Blue project—did you take to that right away?

A: Well, I liked the music very much but I didn’t play too much of the modal music. I was still interested in the changing of keys and harmonies.

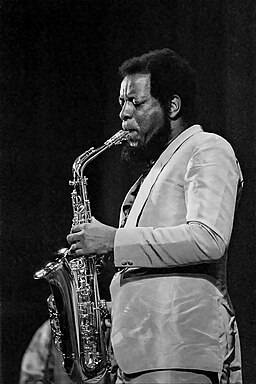

Ornette Coleman, 1971

Q: And how about Ornette when he surfaced? There was this big controversy, it seemed to split the jazz community down the middle, the way Bird and Dizzy did in the forties—they either hated it or loved it.

A: Then I didn’t really love it too much or appreciate what he was trying to do in freeing up the elements. It sounded a little tongue in cheek to me sometimes, and less than I like to feel that the music has developed organically through all of the different periods. I felt that Ornette was studying bebop at his last point in his development until some people got ahold of him and said, ‘Hey, wait a minute, you don’t have to do that, you’ve got something of your own.’ And encouraged him to exploit that, so I felt a primitivism, if you will, in his music that didn’t appeal to me that much.

Q: By primitivism you mean it was like the painter Rousseau, who painted without having studied, just painted naturally?

A: Well, in some respects, yeah.

Q: You don’t think he mastered Bird before he went on?

A: No, I know he didn’t. I sat in with him in Paris once and played some duets on standards, and he played that material better than I had thought, but he hadn’t developed it to a mastery let’s say, and this isn’t meant as a criticism necessarily. I just think of this in terms of the education of the jazz musician, which has to entail study of each development in the music, just as the classical musician studies Bach and Beethoven, etc. That’s what would end up with one being a well-educated jazz musician, and I felt that Ornette had skipped some of that.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Lee Konitz, as a member of the Stan Kenton Orchestra, play on a 1954 recording of “Lover Man”

.

Q: Your own playing has changed over the years…

A: Yes, and along the way people have had comments and reactions to my playing. For example, I might finish playing a set and someone would come up and say, ‘I sure liked the way you played back in 1949–how come you don’t play like you used to play with Tristano?’ And my first thought was because I’m not playing with Tristano! (Laughter)

Q: When you played with Stan Kenton, starting in 1952, did you alter your style to fit into that totally different situation? Did it change your way of playing?

A: Well, by definition it did—I had fifteen people belting out the backgrounds and things and I had to really take a deep breath and huff and puff to be heard. And there’s less opportunity to really be able to just take your time and improvise in that situation. You have one chorus to play or sixteen bars, and you want to play definitively in that short period of time, and it’s got to fit the background, so the tendency would be to be a little more definite about the way you would play. So there was just less improvising involved in that situation.

Q: But Kenton did give you some good solos…

A: Well, I took advantage of them, I appreciated that. He was a good guy to work for, he was very validating, he loved to build up the guys and give them good feature spots. And also, it was the first and last steady gig I ever had—my last steady gig was in 1952! It was very special to me; you know, a big band traveling around and sharing all those experiences, it’s very special, especially for a young person as I was then.

Q: Is there anything we haven’t talked about that you would like to?

A: Well, we haven’t talked about sex! (Laughter)

Q: A friend who studied with you in the sixties once told me that you recommended that your students have sex regularly, that it helps one’s playing….

A: Wrong, I never said that. Lie, he lied…. (Laughter)

Q: But you must have mentioned sex for a reason—don’t you think there’s some kind of connection between music and sex?

A: They say that’s true, yes…

Q: Who says?

A: A few guys… (Laughter)

Q: Do you think jazz is sexy music?

A: At its best, certainly. I like to think of it as an aberrated type of sex, though; most jazz tends to sound a little aberrated to me in that sense, a macho kind of thing, if you will. I like to think of it more as spiritual sex.

Q: There has been so much in the media about musicians, especially bebop musicians, using drugs—I’d like your thoughts on this.

A: Well, my first thought is that those bebop musicians seem very tame next to all the rock people that are around, except for a few heavy users—but whew, we’re not quite as raunchy a lot overall. I think in all of the arts that most of the great people have done something to alter their consciousness to get a perspective they couldn’t get in a normal, daily look at things. And I know this personally: I used to smoke pot when I was growing up, and it worked, it did exactly what I wanted it to do, but the side effects were rather debilitating so I stopped smoking pot. And I decided that it was much more satisfying and more consistent for me without it. The ups and downs were too severe for me.

Q: But when you were coming up, Lee, heroin made terrible inroads into the jazz community, especially the bebop community…

A: The heavy drugs always scared me to death. I didn’t like being around people like that, I never could identify with that. Fortunately, that saved my life I think. I heard the effects of it, and there’s no denying that Charlie Parker played some great music under the influence of those drugs, and that it’s the final product we’re interested in. But I believe that it’s possible that one can create without that messing around with the consciousness, just through living a spiritual life and working hard at it. So when I see drug use around me now it almost seems chronologically out of order to see people still going through that archaic routine of having to “prime” themselves to perform. As a matter of fact, I was completely turned off recently when I saw that the rhythm section I was going to play with were all getting stoned. I felt a complete dividing phenomenon going on and I couldn’t relate to them for the whole evening because of that.

Q: Another touchy subject is race, with sensitivities about who is most validly playing the music…

A: I think that in terms of white people playing in the black music, many times when I was younger I felt very definitely apologetic for playing this music. I didn’t feel totally justified, but I didn’t grow up in the gospel church or anything like that, though by now I feel I have credentials. All I’m trying to do is play theme and variations, and by doing that with some kind of real spirit I believe there’s a place for all of us who are trying to do that. But I am the first to acknowledge the people who were the important people, and those were black musicians.

Q: When you were coming up did you get any heat, did you experience any Crow Jim?

A: The line was when a black musician would hear me play and come up and say, ‘You play as beautiful as ever,’ which means ‘You still ain’t swingin,’ so I accepted that, that’s the way it is for them. But I know what I’m after, and thankfully I can continue to pursue it. The spiritual part of this music far transcends all of those considerations, and anyone interested in the music will appreciate that certainly.

.

.

___

.

.

Postscript: The evening following Lee’s concert, my friend Michael provided Lee with a place to stay in his San Francisco home before he traveled back to New York City the next day. Some days later, a mutual friend had a brass plaque made and installed on the footboard of the bed Lee had used. It stated simply, “Lee Konitz Slept Here.”

.

.

photo by Fred Price

Lee Konitz at the 5 Spot, New York, c. 1966

.

___

.

.

Bob Hecht, as part of his Joys of Jazz Podcast series, recently produced an episode on Lee and his unique focus on pure improvisation. It can be heard by clicking here

.

.

Listen to Lee Konitz play “Blue Ballad”

.

.

.

Thanks to Brian McMillen and Fred Price for allowing use of their photographs

.

.

.

Hi Bob,

I finally got around to reading (and listening) to this sweet interview. As you may remember I was the audio guy on the gig. Reading your print version, I remember being there and the wonderful feeling of the whole day–the vibe was hip. As Lee was warming up for his first set, he was fooling around with his horn, short little riffs and bits of tunes and things, and he turned to us with a smile and said, ” I love warming up. It’s when everything is possible and great.” (I’m sure he said it better, but you get the idea).

The day remains one of my favorite jazz memories.

Thanks –again.

Witt Monts, Berkeley, CA