.

.

“Album Unfinished,” a story by Geoff Polk, was a short-listed entry in our recently concluded 54th Short Fiction Contest. It is published with the permission of the author

.

.

.

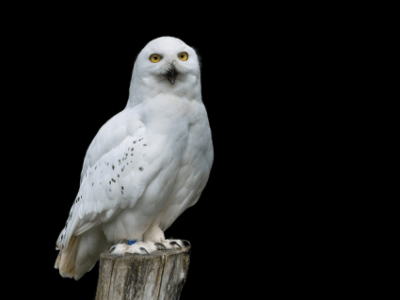

Image by moonzigg from Pixabay

..

.

Album Unfinished

by Geoff Polk

.

…..Jeremy had a job as a guard at the art museum. He didn’t know a lot about art, and sometimes felt foolish when people asked him about a particular painting and he struggled to say something intelligent. But he liked the quiet. It gave him time to think. And there was a benefit in not being too emotionally invested; he didn’t look at Miro and sigh I could never do that, which is what he did listening to great jazz musicians. He guessed he could be considered a failed musician, but he didn’t like to think about it that way—that if you’re not at the top, or even able to make a living as a musician, then you missed the boat. He didn’t like the competitive nature of music. But sometimes it was impossible not to think that way. Musicians were always sizing each other up.

…..Midway through his shift, staring at a Chinese ceramic gourd from the 900’s, he snapped out of his reverie, hearing a woman speaking behind him.

…..“What is the technique?” she said, with a German accent. He turned and followed her gaze to a delicate bowl with impressionistic swirls.

…..“I’m not sure. I guess I’m more of a contemporary man.”

…..“And what is that?”

…..“Excuse me?”

…..“A contemporary man?” She laughed, a sip of tart lemonade. “Sorry, my jokes are bad, especially in English.”

….. She looked like an artist. Short hair, a little askew, a touch of gray. Probably abstract or political art. She slowly walked away through the dimly lit gallery, pausing at a case, her reflection grafted onto a flowered vase.

.

…..Jeremy had woken up that morning thinking about the saxophone player George Coleman. He didn’t know why. It’s not like Coleman was a jazz legend. Then, dressing in his guard attire—black jacket and tie—he heard Coleman come up on his Spotify Daily Mix. He considered the coincidence a validation from the gods of jazz, an omen of some kind. He wasn’t very spiritual, but Jung’s concept of synchronicity did made sense. And there was an actual Church of John Coltrane in San Francisco, so who was he to doubt? Jeremy had heard George Coleman once at a club in Toronto. Coleman had been Miles Davis’s saxophonist on several albums in the period between Miles’s brilliant quintet with John Coltrane and the later, equally stellar band with Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, and Tony Williams. On several of Miles’s Columbia records, Coleman played flowing rivers of notes in solos on “Seven Steps to Heaven” and other songs. He was underrated, recognized as an excellent player—who else would Miles pick, the man with impeccable taste in choosing musicians, repertoire, arrangements, the spare notes he’d paintbrush a song with, not to mention his sartorial hipness—but how could Coleman compare with the innovative saxophonists who came before and after him? Coleman was in the middle, between greatness and the everyday worker plugging away in the world of making music. Of course, even the greats had to work at it, too. But by itself? Just by working hard?

…. Jeremy went to Berklee, virtually the only jazz school in the mid-1970s, but he couldn’t find a career for himself in music. He wasn’t top level, and even those players found it hard to make a living. Even now, Berklee grads had to share apartments, making little at Sunday jazz brunches, working as servers or giving music lessons to eke out a living.

…. Jeremy made a cup of coffee before heading to work, then put on his black walking shoes. Clunky monsters of mediocrity but with good support for his fallen arches, he considered them a symbol for all he hadn’t achieved.

.

….At lunch break Jeremy carried his tray to a table by the large windows that looked out on the museum’s courtyard. As he sat down he noticed the woman who had asked him about Chinese ceramics sitting at the next table, directly facing him. She stirred sugar into her coffee in a slow, deliberate manner. He watched the veins on the back of her hand as she stirred, then looked up at her face. Her eyes, unguarded, looked into his without staring. He saw knowledge in her eyes. She knew things, he was sure, a lot that he didn’t know, that he would only learn with time, if then. He suddenly was aware that the light had changed—the sky had grayed, almost imperceptibly. He finished his sandwich,stood up, his chair scraping loudly, and glanced at her as he passed her table. She could be a great artist, she could be anyone, he guessed it didn’t matter. He nodded to her, the acknowledgement you give people, without words, I understand you. She nodded back, yes, no words necessary, we’re here and the look is also, definitely, a kind of encouragement.

.

….Jeremy’s afternoon shift was in the Paul Klee exhibition currently on tour at the museum. To pass the time, Jeremy liked to pick an artwork, one not overly popular, and really look at it each time he strolled past. If no one was in the gallery, he would stand in front of it, not looking at the note card that explained. He would forget the time period, the artist, its cultural weight, and just look, as if he had chanced upon it in a forest or a vacant lot. He had done several shifts in the exhibit and felt a kinship with the quirky daffiness of Klee’s shapes, the lines and circles running around like misfits bearing the weight of the world lightly. In high school he turned in an assignment—on the Faulkner novel Intruder in the Dust—in which he wrote a sketch of each character alongside a Klee print he selected. The teacher didn’t know what to make of it and gave him a C. He was always doing things like that—not following the assignment. His wife divorced him when she decided, after two years of marriage, that he wasn’t serious enough about things like a career and mortgage.

….But he wasn’t that carefree person now, well into his 30’s, hearing the ominous sound of the approaching waterfall of 40 as he rowed heedlessly down the river. But he wasn’t lazy; he didn’t accept the assessment that he suspected his family and friends held, who still were saying he had potential, that he would make a great—what? They weren’t sure. He was busy, scrambling for gigs, forming bands, ending them, joining bands, quitting when it was time. He wanted to be heroic but didn’t know how, not like the saxophonist Rahsaan Roland Kirk who he heard at a club one month after Kirk’s stroke at the age of 41. Kirk was helped on stage with a walker, but when he started to play, he conjured magic out of the smoky air, and you couldn’t tell he was playing three saxes with one hand.

…..Jeremy circled through the Klee exhibit, which followed his career—in Switzerland, in Egypt, his response to the Nazi invasions. Jeremy read a quote on the wall, from early in Klee’s painting life: “I realized I was an artist.” Jeremy stopped. A chill shot through his body, and at the same time he felt too warm. He wanted to believe that about himself, that he was an artist. He suddenly realized he had lost his art, his music, by minimizing it, by not accepting, claiming his music. It seemed the world was constantly minimizing it and he was going along. Don’t—do not minimize—he was realizing, these years later. He felt dizzy.

…..“You are an artist,” he heard a voice speak from behind him. He started to turn but suddenly the woman from the ceramics gallery was in front of him. He was sweating. She put her hand on his arm so briefly that he wasn’t sure she had. He must have looked as confused as he felt, hearing her speak the words in his head.

….“You said that,” she said.

….“I did?”

….“What is your art?”

….“Music—jazz—I play bass.”

….She looked at him as he did at Klee, taking him in, not as a critic. “I’m only here a short time. But I’d like to hear you play.”

….Jeremy marveled at how comfortable she seemed to be with herself, striking up conversation with strangers. Maybe people who are alone—either in their relationship status or in how they viewed the world—had special antennae to seek out others, try to form friendships or at least talk about what mattered to them. They had to share it with someone or they’d go crazy.

….A guard approached Jeremy to switch out their rotation. He turned to the woman. “Excuse me,” he said and indicated he had to move on. She nodded and turned to Klee’s work “The Limits of Reason.” Jeremy had studied the painting on earlier rounds at the exhibit. It depicted a dark reddish circle—a sun, a blood moon, a balloon, an eye—over a loose splash of orange, below it a scaffold of lines, the outlines of enclosures—rooms, buildings—containing a figure or compass with arms in four directions.

…..As he left the gallery, he realized that he hadn’t told her where he was playing that night. And he hadn’t asked about her, although he was sure she was an artist, in fact very likely could be here to consult with the museum about her work in a future exhibit. He probably hadn’t seemed very friendly to her. But he felt she understood him in some way. He turned to look for her but she was gone.

.

….At his gig that night Jeremy felt inspired. Bass players were not the stars of a band, but it couldn’t exist without the heartbeat they provided, but more than that, the bass could either inspire or deflate the band in some undefinable but very real way. The quartet was playing at close to their best and they smiled outwardly or inwardly as they played, because they loved this. Jeremy kept looking out at the audience. He felt sure he would see the woman from the art museum, even though he hadn’t told her his name or where he was playing.

….But she didn’t appear that night, or at the art museum the next day, when he casually made more rounds than usual, and ate lunch at the same table as before, hoping to see her. The following night, the gig had gone well, maybe not as inspired, but that was the nature of music. You couldn’t plan how it would turn out. Afterwards he had a bite and drink with the band. He told them his ideas for a new album.

.

….It was almost two when he got back to his apartment in Lakewood, but he felt like walking. He walked to the lakeside park and down a dark path that led to the water. He sat on a bench and looked out at the city skyline across the lake. He thought about his disappointment in not seeing the woman. He would have to do this alone. He and the band were tight and listened to and depended on each other, but there was no person, book, painting, concert, or recognition that would light a shining path for him. Maybe it wasn’t a shining path, but his. His eyes followed the waves as they crashed over the rocks. On top of a pylon down the walkway, something was glowing. He stood up and walked slowly closer until he could make it out. It was an owl, pure white, perched on the concrete pylon, facing the dark water. As Jeremy approached, It swiveled its head backward, uncannily, and looked at him, then quickly back to the lake. It kept doing that, looking out at the lake, back at Jeremy, the wind ruffling its feathers, pausing longer and longer each time it turned until it fixed its gaze steadily at Jeremy, seemed to see him.

.

.

___

.

.

Geoff Polk lives in Cleveland, where he write poems, stories, and nonfiction, and plays jazz saxophone and clarinet. He teaches English composition and literature at Lorain County Community College. He attended Berklee College of Music and received an MA in creative writing from Cleveland State University. He was editor of the literary magazine Whiskey Island. Geoff’s poems and fiction have appeared or are forthcoming in Cobalt Review, Brilliant Corners, Voices of Cleveland, The Little Magazine, Context South, Black River Review, Green Fuse, Coventry Reader, and elsewhere. Nonfiction publications include articles and reviews on literature and jazz. He has interviewed David Foster Wallace (anthologized in Conversations with David Foster Wallace, University of Mississippi Press), New Orleans music documentarian Stevenson Palfi, jazz trumpeter Benny Bailey, and authors Ken Kesey, Studs Terkel, Nat Hentoff, and others.

.

.

.

Listen to Miles Davis play “So Near, So Far” from the 1963 album Seven Steps to Heaven, with George Coleman (tenor sax), Tony Williams (drums), Herbie Hancock (piano) and Ron Carter (bass)

.

.

Love it. Hits home. Says more , speaks, no sings more to me than you can know. Not one wasted sound- like great jazz. You can’t be a real academic- too hip, too wise, too real – I despise academics. This is deep and it is art which means not many will get it- like great jazz.