.

.

In a 2004 interview, A’Lelia Bundles, the great-great granddaughter of Madam C.J. Walker, discusses the daughter of former slaves who became one of the 20th Century’s most successful, self-made female entrepreneurs.

.

.

___

.

.

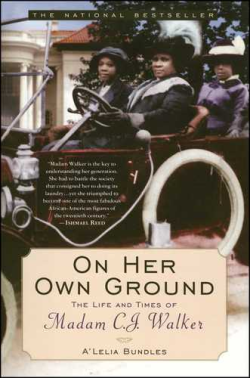

A’Lelia Bundles, author of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker

.

___

.

Born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867 on a Delta, Louisiana plantation, Madam C.J. Walker — the daughter of former slaves — transformed herself from an uneducated farm laborer and laundress into of the twentieth century’s most successful, self-made female entrepreneur. Orphaned at age seven, she often said, “I got my start by giving myself a start.”

During the 1890s, Sarah began to suffer from a scalp ailment that caused her to lose most of her hair. She experimented with many homemade remedies and store-bought products, including those made by Annie Malone, another black woman entrepreneur. In 1905 Sarah moved to Denver as a sales agent for Malone, then married her third husband, Charles Joseph Walker, a St. Louis newspaperman. After changing her name to “Madam” C. J. Walker, she founded her own business and began selling Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower, a scalp conditioning and healing formula, which she claimed had been revealed to her in a dream.

To promote her products, the new “Madam C.J. Walker” traveled for a year and a half on a dizzying crusade throughout the heavily black South and Southeast, selling her products door to door, demonstrating her scalp treatments in churches and lodges, and devising sales and marketing strategies. In 1908, she temporarily moved her base to Pittsburgh where she opened Lelia College to train Walker “hair culturists.”

To promote her products, the new “Madam C.J. Walker” traveled for a year and a half on a dizzying crusade throughout the heavily black South and Southeast, selling her products door to door, demonstrating her scalp treatments in churches and lodges, and devising sales and marketing strategies. In 1908, she temporarily moved her base to Pittsburgh where she opened Lelia College to train Walker “hair culturists.”

By early 1910, she had settled in Indianapolis, then the nation’s largest inland manufacturing center, where she built a factory, hair and manicure salon and training school. Less than a year after her arrival, Walker grabbed national headlines in the black press when she contributed $1,000 to the building fund of the “colored” YMCA in Indianapolis.

Walker moved to New York in 1916, and once there, quickly became involved in Harlem’s social and political life, taking special interest in the NAACP’s anti-lynching movement to which she contributed $5,000. By the time she died at her estate, Villa Lewaro, in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, she had helped create the role of the 20th Century, self-made American businesswoman; established herself as a pioneer of the modern black hair-care and cosmetics industry; and set standards in the African-American community for corporate and community giving.*

Walker’s biographer, her great-great-granddaughter A’Lelia Bundles, visits with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in a March 11, 2004 interview.

.

.

___

.

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Madam C.J. Walker; c. 1914

.

“As a pioneer of the modern cosmetics industry and the founder of the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, Madam Walker created marketing schemes, training opportunities and distribution strategies as innovative as those of any entrepreneur of her time. As an early advocate of women’s economic independence, she provided lucrative incomes for thousands of African American women who otherwise would have been consigned to jobs as farm laborers, washerwomen and maids. As a philanthropist, she reconfigured the philosophy of charitable giving in the black community with her unprecedented contributions to the YMCA and the NAACP. As a political activist, she dreamed of organizing her sales agents to use their economic clout to protest lynching and racial injustice. As much as any woman of the twentieth century, Madam Walker paved the way for the profound social changes that altered women’s place in American society.”

– A’Lelia Bundles

.

___

.

JJM As an introduction to Madam C.J. Walker — your great great grandmother — the writer Ishmael Reed wrote, “Madam Walker is the key to understanding her generation. She had to battle the society who had consigned her to doing its laundry, yet she triumphed to become one of the most fabulous African American figures of the twentieth century.” Madam Walker, born Sarah Breedlove, was orphaned at a very early age. What characteristics did she possess that allowed her to turn her vulnerability as an orphan into resolve and resilience?

AB One explanation is that she was a genius. In every generation there are geniuses like Henry Ford or Bill Gates or Andrew Carnegie, so let’s use that characterization as the headline. In addition, she was a very resilient child. There are many children of poverty who overcome very difficult circumstances, and in a family where everyone doesn’t succeed, sometimes there are children who possess the resilience necessary to turn the difficulties into positives. Because she had so much loss in the early part of her life — including the death of her parents — rather than being beaten down by it, it made her a fighter.

JJM Following the death of her parents, among the difficulties she encountered was dealing with an abusive brother-in-law. What did she do once she got away from that?

AB She married at age fourteen in order to get a home of her own and escape this cruel brother-in-law. After she was married she had her only child, A’Lelia, at age seventeen. Her first husband, Moses McWilliams, died when she was twenty. So, by the time she turned twenty she had experienced more loss and abuse and deprivation than many people experience in a lifetime. Once Moses died she knew that she was not going back to live with the sister and brother-in-law. Instead, she moved up the river to St. Louis, where she had three brothers who were barbers. For the next eighteen years she struggled as a washerwoman, trying to save enough money to educate her daughter. During this time she became very influenced by some of the women of the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, which was located very near her brother’s barbershop. The women of the Church had a long tradition of reaching out to those in need. And these women gave Madam Walker — at that point known as Sarah Breedlove McWilliams — a vision of herself quite different from that of an illiterate washerwoman.

JJM There was some speculation that her first husband had been lynched.

AB Yes, and it is something that is fabricated, yet it gets repeated so many times. In doing the research, the first time I discovered this appearing in print was in a three or four part series on Madam Walker in the Pittsburgh Courier during the forties, and it was very clear that the writer used a lot of creative and literary license. For example, he made up a name for her first husband, and speculated that he rode off on a horse across the levy — which of course he would have no way of knowing. He then wrote that he was killed in a race riot in Greenville, Mississippi. I did a lot of research on riots and lynching in that area, and surprisingly, there is a lot of documentation on the lynchings, because people in the communities were proud of this crime, and there were people who kept records of it. The other thing that I believe proves her husband was not lynched is because Madam Walker was such an outspoken advocate of the anti-lynching legislation. If her husband had indeed been lynched, she would have mentioned that in some of her advocacy. The lynching story is a made-up story.

JJM In the prologue to your book, you write, “As a pioneer of the modern cosmetics industry and the founder of the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, Madam Walker created marketing schemes, training opportunities and distribution strategies as innovative as those of any entrepreneur of her time.” Can you talk a little about her business?

AB When Madam Walker started her business in 1905 – 1906, there was no national or international cosmetics industry. We take for granted now when we go into the drug store or the grocery store that there will be thirty kinds of shampoo, and fifteen kinds of conditioners and hair ointments and other hygiene and cosmetics products. But in 1905, Madam Walker and women like Elizabeth Arden and Helena Rubenstein were creating what is now a multi-billion dollar industry. For the most part, beauty products of that time were created in people’s homes, or perhaps a local company had very limited distribution. These women carved out a niche that was being ignored by the larger corporate world — making products that appealed to women.

Madam Walker’s system used a vegetable shampoo and an ointment that contained sulfur to heal scalp disease, and promoted hygiene and grooming. At the time, most women only washed their hair once a month. People bathed very irregularly because so few of them had indoor plumbing, electricity or central heating. After she developed this shampoo and what she called her “wonderful hair grower,” she began to sell those products door to door. As it became popular, she traveled throughout the United States and began to train other women to be her sales agents. Her mail order operation then began to grow, and she could see that advertising was a very critical and important way to expand her business.

JJM Thomas Fortune, editor of the New York Age, one of the nation’s most widely read black newspapers of the time, wrote, “It is generally the case that those black men who clamor most loudly and persistently for the purity of Negro blood have taken themselves mulatto wives.” The activist Fannie Barrier Williams wrote, “What our girls and women have a right to demand from our best men is that they cease to imitate the artificial standards of other people and create a race standard of their own.” National Association of Colored Women member Nannie Helen Burroughs wrote, “There are men right in our own race, and they are legion, who would rather marry a woman for her color than her character.” What was the black man’s standard for beauty during this era?

AB I don’t want to generalize and say that all black men had identical interests, but the standard for beauty in America during that era was European. The color consciousness that permeated America also infected the black community, so the people who were light skinned often had more privilege. Within families, it was sometimes felt that the lighter skinned member of the family might be able to get the best jobs. So, there were also economic reasons why people made decisions based on skin color. But, while mulatto and light skinned women were sought after by black and white men, there were plenty of dark skinned women who managed to be married.

JJM Along those lines, Burroughs said, “If Negro women would spend half the time they spend on trying to get white, to get better, the race would move forward apace.”

AB Yes, that is probably true. Similarly there has always been ambivalence on the part of women regarding how they should use their cosmetics — whether or not to dye their hair blonde, how much makeup to wear, how much eye shadow to apply — and there will always be that tug and pull, but this was especially apparent in the early twentieth century, a time when women who even wore makeup were considered either actresses or whores. People were still developing their attitudes about what was appropriate. There is a great deal of evolution since the early twentieth century regarding the aesthetic of what is acceptable in the black community. People of the era felt the need to conform. In the sixties, hair was liberated for people of all colors. In the musical Hair, white kids let their hair grow long, and black kids let their hair grow into Afros, so everyone was liberating himself or herself. Today, it is interesting that the whole range is acceptable, whether it is dreadlocks or beads with blonde hair. Some people have psychologically painful hang ups about their natural hair, and other people are just experimenting and changing their styles on a whim.

JJM Booker T. Washington had an interesting view of the cosmetics industry. He wrote to New York Age editor Fred Moore that he had come to “view with alarm” the “considerable amount” of “clairvoyant advertising, hair straightening advertising, and fake religious advertising” that appeared in his newspaper.

AB Yes, and I think most of those were white owned companies who were playing on some of the insecurities African Americans felt at the time. Remember that during slavery there was a great deal of shame imposed on African Americans by whites regarding their skin color and hair texture, and some of those insecurities remained. Booker T. Washington was concerned that people in the black community were being misled by these charlatans who were trying to market what he considered to be hair straighteners — when in fact no one’s hair can be straightened permanently. Madam Walker tried to distinguish herself from that.

JJM You wrote, “When women saw her photo and heard her life story, they clamored to take her course and sit for her treatments.” How did she market her past to generate more business?

AB She very much used her own personal narrative as a way to inspire women. In an era when there was no radio, television or Internet, a person speaking at the local church or town hall was very exciting. Because she was a woman who might arrive in a chauffeured driven car, possibly wearing a fur, and who was a bit more sophisticated than the people in the town, she was an attraction. She used some of that public persona to get people interested in hearing her story. Once they heard her story and how she had become economically independent, they became even more fascinated.

JJM I was amazed by her courage. The way that she reached out, for example, to Booker T. Washington, took a lot of guts. Here was a woman who grew up in poverty and was only a few years into her business when she started to appeal for his attention…

AB Some of these early coping mechanisms she used to survive the trauma of being an orphan as well as an abused young person inspired her. The AME Church, as I mentioned earlier, was also very important for her. The Church has a long tradition of being politically militant, of having effective leadership, and of educating and empowering African Americans. Also, the relationship with some of the women friends she made who were higher in status when she first arrived in St. Louis gave her role models to follow. She took what they had and propelled beyond them.

JJM Regarding her interest in getting Booker T. Washington’s attention, before an assembled audience at the National Negro Business League convention, which included Washington, Walker stood up and, among other things, said, “Perhaps many of you have heard of the real ambition of my life, the all absorbing idea which I hope to accomplish. My ambition is to build an industrial school in Africa. By the help of God and the cooperation of my people in this country, I am going to build a Tuskegee Institute in Africa!” After hearing this, Washington ignored her remark and moved to the next order of business. Why did Booker Washington frequently dismiss her?

AB Well, I think he dismissed her, yes, but that was probably the last time he did so.

JJM Yes, she had tried to get his attention in writing a couple of times prior to that.

AB Yes, she had written to him, she had visited the Tuskegee campus, and they had met each other at previous conventions of the National Association of Colored Women. In the instance you talk about, the 1912 convention, he resented the fact that she tried to take over even though she wasn’t included in the program, or part of his inner circle. She was being pushy, he was a chauvinist, and he didn’t really like other people telling him what to do. As a result, he didn’t want to give in, but after she had made such an impression on others, he couldn’t ignore her any longer. At the dedication of the YMCA the following year, and at the subsequent National Negro Business League convention, he was full of praise for her and was very happy to see her. They got to be so close that when he visited Indianapolis, he stayed at her home.

As Madeline Albright has said, sometimes women should not “shut up,” and at times we do need to interrupt. That is as true now as it was before, and maybe more so. If you sit on your hands and let other people define you, no advances are made, and the only way Madam Walker was going to break that barrier with Washington was to startle him. Afterwards, there was at least a mutual respect for one another.

JJM Yes, concerning her thinking that women really need to stand up for themselves, she said, “I had little or no opportunity when I started out in life. I had to make my own living and my own opportunity. But I made it. That is why I want to say to every Negro woman present, don’t sit down and wait for the opportunities to come, but you have to get up and make them!” She certainly demonstrated that.

AB That’s right. I believe that she really was a visionary in terms of women and economic independence. She was saying all of these things before women had the right to vote, and before they could own property in their own name. She was very aware that there were many women like her who had been widowed or abandoned, who did in fact have to make their own living, and the only way to do so was by doing it themselves. She was a tremendous advocate for women’s independence. In 1917, the year before Mary Kay was born, she was having conventions of her sales agents, giving prizes not just to the women who sold the most products, but to the women who contributed the most to charity and political causes. She had a vision of her sales agents — made up of economically independent women — using their money to make a difference in their community.

JJM And I got the sense that this vision — while it was a great business strategy — came from the heart. It didn’t appear to be the least bit fabricated…

AB Yes, I believe you are right. She came up with many of these ideas herself. She was quite influenced by her spirituality and her religious connections to the AME Church, as well as to the women’s club movement of the times, including the National Association of Colored Women. By attending those conventions and by becoming a part of that group of women, she gleaned ideas from them. Her idea for organizing her agents into local, state and national clubs came from the structure of the NACW. It is also likely that her association with the NAACP radicalized her politics as well.

JJM Your grandmother A’Lelia once said of her mother, “Mother rules with an iron hand and forces her opinion upon me regardless of what I may think.” What was their relationship like?

AB As many parent/child relationships are, theirs was very complicated. Madam Walker rose up from abject poverty, founded her own business, and eventually became one of the most famous people in the country. As a mother, she intentionally spoiled her daughter but also wanted her to be successful. As a result, A’Lelia Walker became a very complicated person. It is pretty simplistic to say, as some do, that Madam Walker made the money and A’Lelia Walker squandered it. In actuality, A’Lelia had a lot of great ideas, but only one person could lead, and she often felt overshadowed or dismissed by her mother. It was very difficult for her to live up to her mother’s expectations, which is probably the case for fifty percent of the population, it is just that the rest of us are not as famous.

JJM Did she take any risks when moving her business to Harlem?

AB The move to Harlem didn’t really involve risk, and for the most part it was all positive. She didn’t actually move the business to Harlem — it stayed in Indianapolis — but she moved her personal residence to Harlem and had a beauty salon and a school in the residence in Harlem. It was a beautiful, strategic move to keep the manufacturing operation in Indianapolis, where it was cheaper to do business, and yet have a high profile presence in Harlem since it was becoming a Mecca for African American politics and culture.

JJM How was she received in Harlem when she arrived?

AB Her salon opening was written up under headlines. She was a big heroine by the time of her arrival in Harlem, and not just because of her success as an entrepreneur, but because of her work as a philanthropist and political activist as well. She was very favorably received.

JJM Her political evolution was pretty fascinating. Can you talk a little about where she started and where she wound up politically?

AB I don’t know that she started any place politically, but as she became more exposed to W.E.B. DuBois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and A. Phillip Randolph, her political views became more radicalized. It could be said that because she was a woman living in an era when so much chauvinism existed, she was already radicalized. She shared some of Booker T. Washington’s views regarding the importance of having a skill and of being economically independent. I don’t believe she shared his views about standing back and not integrating — they probably departed on some aspects of that. While she was certainly more politically radical than he was, she had a great deal of respect for him. She may not have agreed with everything he stood for, but she understood his power.

By the time she made the move to Harlem, she had been approached by so many people in an effort to get her support of a particular cause that she had to sort them out. And, unlike some people who become more politically conservative after achieving wealth, she actually became more politically radical. The source of her wealth was other black people, so she didn’t feel compelled to support the causes that white people or conservatives did. She became very outspoken about lynching, discrimination against African American soldiers, and any kind of civil rights discrimination, and evolved into a politically militant person. It is interesting that when she applied for a passport in hopes of observing the Paris Peace Talks — she had a great deal of interest in the former German colonies like Togo, Cameroon and German East Africa — it was denied because she was described by a spy for the War Department as a “Negro Subversive.” Those charges were based primarily on her outspokenness on lynching and discrimination.

JJM Her attorney, Freeman Ransom, was skeptical of some of her political affiliations, including that with the International League of Darker Peoples. He said to her that he was “beginning to grow seriously apprehensive lest you will impair your usefulness by becoming identified with too many organizations fostered by highly questionable characters.”

AB Yes, and he was probably right about that specific organization, but, as time goes on, what appeared radical then is now part of the mainstream. For example, A. Phillip Randolph is looked upon by most Americans today as a brilliant man who pulled together the Pullman Porters Union and created the March on Washington in 1963, but he was viewed as out of the mainstream — of being too radical. Martin Luther King was considered a radical by many people as well. You don’t make any progress unless you do something that challenges the status quo, and Mr. Ransome, for all of his brilliance and all of his contributions, was quite conservative in his outlook. He was trying to protect his client, and his advice to her in terms of that particular organization was very positive. But in contrast to that, he was very dismissive of Randolph, who ultimately turned out to be one of the most important civil rights figures of the twentieth century.

JJM It didn’t appear that any of her political stances ever interfered with her business.

AB No, they didn’t, and they really couldn’t, in many ways. Even though Mr. Ransome was fearful that her opinions may, as he said, “circumscribe” her business, since her customers were black, they were not upset by any of her political alliances. Sure, the government might be opposed to some of the things she stood for, but they weren’t using her products and weren’t the source of her income. The one thing that her political stances did do was prevent her from getting a passport, but dozens of African Americans were denied passports at the time because President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of State Robert Lansing didn’t really want to have the pesky issue of racial discrimination brought up during the Versailles talks.

JJM She had an interest in building a college in Africa. Did she get far along with that?

AB Not very far at all. It was an interesting dream that she had, but nothing that ever materialized.

JJM Perhaps it was something she would have accomplished had she lived longer?

AB Maybe, but probably not. Considering the transportation of the time, the logistics of that would have been so difficult. It was certainly a laudable goal but not easily attainable for the era.

JJM Madam Walker’s name became synonymous with hair straightening. You wrote, “Derisively dubbed the ‘de-kink queen,’ she had maintained until the end that she was a hair culturist, not a hair straightener.” Was this an unfair legacy? Is she remembered in a way that does her an injustice?

AB Certainly she is to those people who only associate her with that. It is an incomplete legacy, and an ill informed legacy.

.

___

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Madam Walker driving her Model T Ford

Indianapolis, 1912

.

“(Madam Walker is) the clearest demonstration I know of Negro woman’s ability in history. She has gone, but her work still lives and shall live as an inspiration to not only her race but to the world.”

– Mary McLeod Bethune

.

___

.

The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker

by

A’Lelia Bundles

.

.

About A’Lelia Bundles

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

AB My hero while I was in high school was W.E.B. Du Bois. His intellect struck me. I read Souls of Black Folk at a very pivotal point in the sixties, while I was in high school, and it was the first piece I read that was a complex and nuanced treatment of race in America. I was pleased to see someone articulate things that resonated so much with me.

JJM Was he an inspiration in your career as well?

AB I don’t know if he served as an inspiration for my career, but it was personally inspirational because it challenged the myth that black people are not very bright — which many people still believe. Du Bois went to Harvard, which is where I went as well, so his attendance there was particularly meaningful for me.

The inspiration for my writing was more because of my parents, who were probably my biggest influences. My father was a Journalism major at Indiana University in the forties, and when he graduated from college, since the Indianapolis Star was not ready for a black writer, they hired him instead as circulation manager, where he oversaw the delivery of the paper. We shared a love of writing and journalism, which was the icing on the cake for me.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on March 11, 2004

.

.

* Text from publisher.

.

.

.