.

.

In a 2000 interview, Ean Wood, author of The Josephine Baker Story, discusses the entertainer’s groundbreaking, extraordinary life

.

.

___

.

.

…..The effervescent smile of Josephine Baker is easily recognizable. The mellifluous tone of her voice is legendary. Epitomizing the adage “all that glitters is not gold,” her life was plagued with broken marriages, discrimination, poverty, and eventually illness.

…..In his book, The Josephine Baker Story, author Ean Wood, who previously wrote of George Gershwin’s life, presents us with a portrait of a truly remarkable woman whose charm, vivacity and captivating personality live on long after her death.

…..Our September, 2000 email interview with Ean Wood covers her youth, her move to Paris, her role during World War II, and other revealing details of her life…

.

.

___

.

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Josephine Baker in Banana Skirt from the Folies Bergère production “Un Vent de Folie”, 1927

.

.

Listen to Josephine Baker sing “J’ai Deux Amours”

.

.

___

.

.

JJM Who was your childhood hero, Ean?

EW Well, that’s kind of a difficult one, because I’ve never really had heroes. In the field of performing arts my earliest interest was in radio, and I can remember when I was about eight or nine being an avid listener to Fred Allen. Which might sound odd from somebody raised in the UK, but my father was devoted to AFN Munich. I guess you could say Fred Allen was the first person I was a fan of.

JJM What inspired you to become a biographer?

EW An interest in people. The fact that everybody is unique, and often strange to other people. Biographies, like good novels or movies, show different ways of behaving. They celebrate the wild unconformity of the human race.

JJM Why a book on Josephine Baker?

EW Josephine Baker was about as wild and nonconforming as they come, as well as being a magnificent entertainer. She was a true instinctive, acting on impulse all the time, whether it was improvising her dancing and singing, enlisting in the secret service during World War Two, fighting bravely for racial equality, having wild affairs or overspending recklessly. For her, to want to do something meant going right out there and doing it, and she showed a lot of people a more instinctive way to live.

JJM Who was the primary inspiration of Baker’s life?

EW There wasn’t any one person. Born in St Louis in 1906, she was steeped from childhood in the music of the city – ragtime and early jazz – and even more in the dancing. It was a time when America was dance-crazy, and new steps were being invented almost every day. She learned every dance-step that came along. A little later in her life, when she’d decided she also wanted to become a singer, she picked up styles and ways of performing from anyone she found had something she could use. Ethel Waters in America, and later, in France, singers like Damia (who was also an influence on Edith Piaf) and Mabel Mercer.

JJM What was her childhood like?

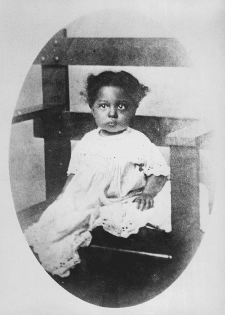

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Josephine Baker in 1908

EW Deprived. And that’s putting it mildly. Deprived both financially and emotionally. Her father walked out on her mother when Josephine was an infant. Her mother resented Josephine for looking like him, and was cold and critical towards her. Her stepfather, who married her mother when Josephine was five, found difficulty getting work – he was a laborer – so the family was mostly supported by her mother taking in washing. She had a younger brother and two younger half-sisters, and they lived in rat-infested hovels with newspapers for wallpaper. From about the age of six she learned to scavenge for food in refuse bins and steal coal from the rail-yards. She once said she only took up dancing to keep warm.

JJM How did she get into show business? What was her most successful U.S. role?

EW She was a natural comic. One of those kids who clown around in school to get attention and to rebel. She combined clowning with all the dance steps she’d learned, crossing her eyes and going knock-kneed and grinning a big goofy grin. And she was doing that in a club she waited table in – this would have been when she was about fourteen – and she was spotted by the leader of a small raggedy street-band (a trio), who hired her to join it. Playing to the queue outside a vaudeville theater she was spotted by the theatre manager, who hired her (and the trio) to fill in for an act that had not showed up. And she was in show-biz.

Her most successful role in the US in her early days was in the ground-breaking black musical “Shuffle Along” – the show that made black entertainers fashionable in the early Twenties and kicked off all that “going to Harlem in ermine and pearls”. She was the comedy dancer on the end of the chorus line who got all the steps wrong, and was so likeable and funny that she ended up being paid nearly as much as the stars.

JJM What most inspired her to leave the U.S. for Paris? Was it a particular event or a series of events?

EW It was a particular event. She was no longer in a show, but appearing at a Harlem club (with Ethel Waters), and wondering how to develop her career. She didn’t want to be just a zany comic all her life – she wanted to be glamorous as well. A rich American socialite, Caroline Dudley, came to the club wanting to cast Ethel Waters as a singer in a “black vaudeville” show she was going to put on in a Paris theatre. Ethel didn’t want to go, and Caroline, on impulse, asked Josephine if she’d join the show as a comic dancer. Josephine dithered nervously for a while, but eventually agreed to go. She was fed up with the racial intolerance she found in mid-Twenties America, even in New York, and had heard that in France Blacks were treated like equal human beings. Also she loved the idea of traveling.

JJM What was going on in Paris at the time of Baker’s arrival? What opportunities existed in Paris that didn’t in the U.S?

EW What wasn’t? These were the “Annees Folles” (as France called the Roaring Twenties). Everybody was on a party celebrating the end of the Great War. Also Paris was the center of almost everything exciting that was happening in the arts – it was full of writers and painters and composers. Many of them were American – people like Hemingway and Gershwin flocked there on visits. They liked being in a city where art was respected – where artists were respected. Also, where you could drink legally.

JJM What was it about Baker that Paris fell in love with?

EW She fell in love with the freedom she found there as a black woman. But she was also a massive success as a performer. Her near-nude erotic pas-de-deux (“Danse Sauvage”) that she performed in Caroline Dudley’s show – as well as her uninhibited Charleston – made her the talk of the town. She was invited to all the best parties, and found herself suddenly a celebrity among celebrities. Artists like Picasso painted her. Nobility socialized with her. Couturiers designed chic gowns for her. And she was now being seen as beautiful as well as amusing. She was having the time of her life. It’s no surprise she fell in love with the place.

JJM So much of Baker’s success seemed centered around the theme of “black woman as exotic creature,” both on stage and on film, yet Paris was considered racially liberated. How did those two go together?

EW They don’t really conflict. It’s one thing to perceive someone as strange and exotic, some wild intuitive creature in touch with her primitive instincts, and a quite different thing to see her as subhuman. If anything, they saw her as superhuman, a person who had not lost touch with her inner self the way (they thought) civilized people had. To some extent, I suppose, she was seen as a curiosity, the latest new sensation. But she was lively and amusing in company, and people enjoyed having her around.

JJM While her stage career was a smashing success, did she have critical success as an actress? What was her most successful film performance?

EW She did little formal acting, on stage or film. Her films were mostly musicals in which she played a thinly-disguised version of herself. What she really loved, and what she was really good at, was relating to an audience, either in a music-hall or a night-club. But she did become quite a good actor in films. Her most successful was undoubtedly “Zou-Zou”, made in 1934. It had the best script, and she had her best co-star, the young Jean Gabin.

JJM One of her ‘husbands”, Pepito, was quite adept at creatively publicizing Baker. What were the most outrageous things he did to publicize her?

EW Well, he wasn’t legally her husband. He was her lover and manager. In fact their “marriage” was one of his publicity stunts. It made a good story – poor black American girl rises to fame and fortune in Paris and marries Italian nobility. Not that Pepito was real nobility either. He called himself “Count Pepito de Abatino”, but in fact he was a Sicilian stonemason.

In the late Twenties, after their “marriage”, they went on a two-year tour all over Europe and South America, and while they were in Budapest a Hungarian cavalry officer started paying attention to her. Pepito slapped his face and challenged him to a duel at dawn the next day. But he made sure to let the officer know it was only a publicity stunt. It worked brilliantly. Reporters were on hand, Josephine screamed realistically while they fought, and Pepito got a scratch on the shoulder. It made all the papers and the officer was a romantic hero among his fellow-officers.

JJM Given the rise of Nazism and racism in Germany, how was she viewed throughout the rest of Europe as she made this tour? How was she characterized by the Axis?

EW In places like Austria and Germany she was disliked – she was abhorred – by the early Nazi movement and by the Catholic authorities. Both saw her as degenerate for her sexy dancing, and the Nazis saw her as racially impure as well. But the majority of the public in those countries adored her. And I ought to say that her dancing was as witty as much as erotic. Like Mae West at around the same time, she found sex not only natural but funny. Nazis, of course, were never very good at understanding funny. When they rose to power in the Thirties she was branded as “decadent” in a pamphlet by Goebbels, along with a number of other famous artists, such as Picasso and the theatrical producer Max Reinhardt.

JJM Baker’s trip to South America awakened her to the specter of racism being a worldwide problem. How did this change her?

EW It helped to strengthen and sharpen the awareness of racism that she’d had from her childhood in the American south. For the first time she spoke out openly about it, writing an angry open letter to several Paris newspapers, complaining that dancing “practiced by a white woman is moral and by a black one transgresses”.

JJM Throughout her career, Baker had tremendous success entertaining predominantly white audiences. How did the black culture respond to her work?

EW She had a certain amount of trouble with the black culture in America, especially in the Thirties. At that time black Americans were increasingly proud of their race’s achievements, especially in the field of entertainment, which was one of the few fields open to them. People like Ethel Waters, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Bill Robinson, etc. etc. were being accepted as entertainers (not just black entertainers) by white America. What the black public resented about Josephine was that increasingly she was singing and dancing in a Parisian style. It was unfamiliar to them, and they felt she was betraying her roots, that she wasn’t proud of being black. Which of course she was.

JJM In addition to a budding film career, Baker, whose singing became more featured than her dancing, performed in an Offenbach operetta called “La Creole”. How did this affect her life?

EW Very little. It proved that her voice was now good enough to handle operetta, and that she could act in a straight piece. And it was a big success with both critics and public, more for her performance than for the piece, which is not one of Offenbach’s best. But she rarely touched operetta again. And in a way she was right. She had much more to offer as a star performer, rather than burying her blazing personality in a conventional role.

JJM As the style of dance Baker was famous for, the Charleston, evolved, and as the swing era brought new styles of dance, such as tap, how did Baker adjust?

EW Not at all. Like I said earlier, this is why for a while black America was a bit suspicious of her. She continued developing along her own lines, as an increasingly glamorous Parisian star. At one point she even had ballet lessons from Balanchine. She went her own way.

JJM In 1935, she spoke out in favor of Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, believing, as Mussolini did, that Haile Selassie enslaved Ethiopians. Baker said she would be “willing to recruit a Negro army” to oust Selassie. Given Selassie’s standing in America, how did this effect her relationship with America, and what impact did this belief have on her return to the U.S. at this time?

EW This was a typical example of Josephine’s quick-fire instinctiveness leading her astray. Being in touch with your feelings is fine, but it can be difficult if they change like traffic-lights, and especially if you haven’t understood the situation. The effect her outburst had when she returned to America to appear in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936 was that it tended to make audiences somewhat hostile to her. And in that show she needed all the goodwill she could get, because the idea of a black girl singing and dancing like a Paris chanteuse was odd and unfamiliar. So she flopped badly. After the Second World War, with many Americans having served in Europe, and with French performers like Edith Piaf and Charles Aznavour coming along, she had no trouble. Americans learned who she was.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Josephine Baker in 1948

JJM When war was declared, Baker volunteered, and was accepted as a member of the Free French. Her role during the war could only be described as heroic, from delivering classified information to the Free French to entertaining American troops in north Africa and Italy. Was this the “role” she was most proud of during her life?

EW Yes. She was made an honorary sub-lieutenant in the Ladies’ Auxiliary of the French Air Force, and after the war was awarded the Legion d’Honneur. For a woman desperate for approval all her life, and getting it mostly from audiences, these honours, earned in a noble cause (she saw the war as only an episode in her fight against racism) were enormously reassuring.

JJM When she returned to the U.S. following the war, and in spite of African-American efforts during the war, she experienced and witnessed the racism she had all her life in her visits to America. What did she do to advance the cause of civil rights in America?

EW A lot. Touring America at the end of 1947 with her husband, bandleader Jo Bouillon, who was white, they had enormous difficulty finding a New York hotel that would accept a mixed-race couple. She felt (rightly) that America was even more racially intolerant then than it had been in the Twenties. To investigate this, she set off incognito (as “Mrs Brown”) to travel through America, especially the southern states. There she attempted sit-ins (years before they became commonplace) getting thrown out of lunch-counters and ladies’ rooms, and going right back in. She began lecturing on civil rights at black universities. On later visits to America, into the early Fifties, she campaigned for integrated audiences and hotels and transport, for equal opportunities in employment. She used all her celebrity to publicize her fight, and got such a reputation as a crusader that the NAACP declared Sunday, 20th May 1951 to be Josephine Baker Day. There was a great celebration in Harlem, and 100,000 people turned out to honor her.

Jack de Nijs for Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Josephine Baker at her Chateau Les Milandes, 1961

JJM At one point, Baker opened up the grounds of her estate, Le Beau-Chene, to children of the St. Charles Orphanage, becoming “godmother” to them. This love for children – what was its genesis?

EW Nothing too difficult there. Like many women she had very strong natural longings to gave children. For some reason she was finding it impossible to produce children of her own, and these dammed-up longings became stronger and stronger in her as the years went by.

JJM As a result of the racism she encountered throughout her life, Baker’s desire was to adopt children from all walks of life and all races, referring to them as her “Rainbow Tribe”. Did she feel this benefited her crusade for international brotherhood?

EW Yes, she did. She and her husband Jo Bouillon lived with the Rainbow Tribe at her chateau in the south of France, which she also ran as a leisure complex, with hotels and sports facilities. It was called Les Milandes, and she used the publicity for Les Milandes to let the world know about her children living together happily and peacefully, as the races of the world could do. She even had plans to use the place as a College of International Brotherhood, bringing hundreds of young people from all over the world to attend courses, so that they could go back home to their countries and spread the word.

JJM Baker eventually adopted a total of 12 children from all over the world. What impact did this have on her personal life – financial security and her marriage?

EW It wrecked them. All through all her campaigning she continued to perform, bringing in money, but she was a poor administrator, and overspent recklessly, both on the children and the chateau. Her husband, Jo, tried to restrain her, but she saw this as trying to obstruct her crusade. They had rows, and eventually split. And Les Milandes eventually got so much in debt that in 1968 her creditors had her, and the Rainbow Tribe, evicted. Fortunately they were saved by Princess Grace of Monaco, who had long admired Josephine’s crusading courage. She found them a villa to live in on the south coast of France, near Monaco.

JJM Ultimately, what is Josephine Baker’s legacy?

EW As a crusader in the Forties and Fifties she advanced the cause of civil rights in America, so that conditions for Blacks improved faster than they might have done without her. As a dancer in the Twenties she brought Afro-American dancing to the attention of European dancers and choreographers, helping to bring about a creative fusion of styles, and as a wonderful mixture of cheerful instinctive vitality and fashionable chic, she was a great influence and example to young people. She showed that being real was better than having over-correct good manners, and that life was for living. She told it like it is. And above all, of course, she was a hypnotic entertainer – magnificently stylish, sexy and witty. People who saw her remember.

.

Studio Harcourt, via Wikimedia Commons

Josephine Baker, 1940

.

.

___

.

.

The Josephine Baker Story

by Ean Wood

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician (thank you!)

.

.

.