.

.

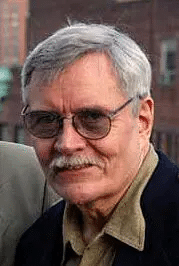

In an interview originally published on Jerry Jazz Musician in 2003, Bessie Smith biographer Chris Albertson talks about the life of “The Empress of the Blues,” one of popular music’s most important figures during the 1920’s and 1930’s

.

.

___

.

.

Chris Albertson,

author of

Bessie

.

___

.

Considered by many to be the greatest blues singer of all time, Bessie Smith was also a successful vaudeville entertainer who became the highest paid African-American performer of the roaring twenties.

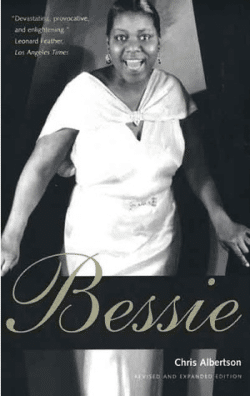

First published in 1971, author Chris Albertson ‘s Bessie was described at the time by critic Leonard Feather as “the most devastating, provocative, and enlightening work of its kind ever contributed to the annals of jazz literature.” New Yorker critic Whitney Balliett called it “the first estimable full-length biography not only of Bessie Smith, but of any black musician.”

Over thirty years later, Albertson polished his work, and includes more details of Bessie’s early years, new interview material, and a chapter devoted to events and responses that followed the original publication.

Albertson, the acknowledged authority on Bessie Smith, discusses the great singer’s career — and the myths surrounding it — in a September, 2003 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita.

.

.

__

.

.

photo by Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress

Bessie Smith, 1936

.

“She was a difficult and temperamental person, she had her love affairs, which frequently interfered with her work, but she never was a real problem. Bessie was a person for whose artistry, at least, I had the profoundest respect. I don’t ever remember any artist in all my long, long years — and this goes back to some of the famous singers, including Billie Holiday — who could evoke the response from her listeners that Bessie did. Whatever pathos there is in the world, whatever sadness she had, was brought out in her singing — and the audience knew it and responded to it.”

– Apollo Theater owner Frank Schiffman

.

.

Listen to the 1923 recording of Bessie Smith performing “Downhearted Blues,” with Clarence Williams on piano

.

.

___

.

JJM Blues singer Alberta Hunter, a contemporary of Bessie Smith’s, said of Bessie, “I don’t think anybody in the world will ever be able to get as much hurt into one song.” You write, “Bessie Smith’s story unfolds during a period when America was beginning to discover what the subculture she moved in already knew: the impact of African-American culture on the entertainment business. But no one could have predicted how far reaching that influence would become. Bessie played a small but significant part in the history of American popular music.” What initiated your interest in Bessie Smith?

CA In 1947, I was a teenager living in Copenhagen, and I just happened to hear a Bessie Smith recording on the radio. At the time, I didn’t understand a word she was singing, didn’t know it was the blues or that she was black I didn’t know anything except that the performance got to me in much the same way that Edith Piaf had gotten to me. There was something compelling about the voice. I then found out that it was a lady named Bessie Smith, and I started looking for her recordings. They were not easy to find at the time, but I found some in a store that sold used records and books. This discovery led to Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and everybody else — a whole new world opened for me. Bessie Smith really sparked my interest in jazz and blues.

JJM You write, “Early writers tended to stereotype her as a big fat mama who drank a lot, fought like a dog, and sang like an angel.” What was your impression of her before writing this book?

CA That was my impression, originally. By the time I got to write the book, I had a reality check. While I had no intention of writing a book — that was something I was asked to do by a publisher — I did spend two years trying to persuade Columbia to put out the complete Bessie Smith recordings, because they were the one company that owned all of them. So, that led to the writing of the book, but by that time, of course, I had become a big Bessie Smith fan, and I had moved to the United States and begun to realize what she was all about, and what race relations were all about. I was totally naive in Denmark.

JJM Bessie was originally published in 1972, and is now being re-released as a new edition. What changes did you make to this edition?

CA When the rights reverted to me, I reread the book. I hadn’t read it since I wrote it, and I was appalled at my own writing, and sort of angry at my original editors for letting it go through. I thought the writing was just terrible. So the first thing I decided to do was to smooth it out and translate it into English, so to speak. Also, I never stopped doing research on Bessie, even after the book was published. After its publication, I heard from people who said they knew Bessie, and they told me their own stories, so I learned a great deal more after the book was published, and I began to wish I had known this while I was writing it. I had organized a card file of my research, which I kept updating, thinking that someday it would be useful. Subsequently, the things I learned were put into the second edition of the book. I also added a chapter at the end to update the reader about events following the printing of the first edition — the usual talk about movie deals, and what happened to the various people in the book. So, the second edition is basically an updating and an expansion of the first.

JJM My understanding is that the information on Bessie Smith was scant and distorted, even in 1972. Is that right?

CA Yes. And because there were so many myths, some took on a life of their own. Many of the people who wrote about Bessie Smith — whether it was an article or whatever — did not bother to verify the myths, so they perpetuated them. They had become so established that they came to be regarded as fact. But some of them didn’t make sense, and when I started writing the book, the first thing I set out to do was to find out what information about her is fact and what is myth.

JJM We will get to these myths in a little while. It is interesting to see who was involved in perpetrating these myths. How did her career begin?

CA It began when she ran away from her Chattanooga, Tennessee home. Her older brother Clarence left with a show, the Moses Stokes Company, which she also wished to join but she was too young at the time. In the meantime she began singing and dancing in the streets with her brother Andrew, and when Clarence and the Moses Stokes Company came back to Chattanooga around 1912, she talked him into arranging an audition. After the audition, they took her on as a dancer, not a singer. Ma Rainey was with the show at the time, and she was the show’s singer.

This is where one of the myths began. The story is that Bessie ran away, and one writer actually had her kidnapped by Ma Rainey in a potato sack and dumped at Ma Rainey’s feet. The stories got pretty wild. The general belief was that she had left with Ma Rainey, and became a member of her show — but it wasn’t Ma Rainey’s show. The story goes on that Ma Rainey taught her how to sing, but people who heard Bessie at the time said that nobody needed to teach her how to sing, she already knew how. If anything, Ma Rainey taught her stage presence. While I am sure that Ma Rainey — being the older and more experienced person — had to have provided Bessie with some instruction and mentoring, it wasn’t singing that she taught. They don’t sound alike at all, either.

JJM It is said that Bessie Smith influenced the likes of Billie Holiday and Janis Joplin. Who inspired her own singing style?

CA Perhaps it was Ma Rainey, although not the style. I am almost certain that Ma Rainey got Bessie on the blues track, but regarding her style, while she may have picked up a little here and there, she certainly had her own approach to it. There wasn’t much outside influence. Ida Cox and Alberta Hunter — great blues singers of that period — both told me that when they started, it was popular songs that they sang. The first song Ida Cox remembers singing was “Put Your Arms Around Me, Honey,” and Alberta sang “Where the River Shannon Flows,” neither of which of course had anything to do with blues. They called Ma Rainey the “Mother of the Blues,” and I think rightly so, but her style was more akin to the male blues singers who wandered around the South, accompanying themselves.

JJM Bessie Smith had quite a work ethic. Where did that come from?

CA That came from her family. Her mother and father died when she was very young, leaving several children behind. The oldest of them, Viola, had to work very hard — she took in laundry to keep the family fed. She was apparently very strict when it came to her siblings. There is a saying in Denmark, “a naked woman soon learns how to weave.” I think out of necessity the work ethic was prominent because it was a necessity.

JJM Some of the stories in her life are legendary. She survived a knife stabbing, often fought with her fists over lovers of both sexes, and even stood up to the Ku Klux Klan. What is your favorite story of her?

CA As far as terrible things happening and having to overcome adversity, the stabbing story was my favorite.

JJM What were the circumstances of this story?

CA She was recording for Columbia Records at the time, and returned to Chattanooga as a star performer. While there, she received numerous invitations to parties, one of which she accepted. It was at a party held at a house on the outskirts of town, and she went there with several of her chorus girls, including Ruby, who was her niece by marriage and a major source of information for my book — in fact, Ruby was a person without whom I could not have written the book. They were having a good time at the house when a drunk man asked to dance with one of Bessie’s girls. He grabbed at her, and Bessie got up and told him to stop that, which he resented. Later, when they left the house, and after they had walked a while, this man from the party came out of the shadows quite suddenly and stabbed her, leaving the knife in her. He ran away and she ran after him with the knife in her until he got away. She asked Ruby to take the knife out of her, but Ruby couldn’t do it. She was taken to the hospital but the next day she was back to performing on the stage. Most people, of course, wouldn’t have been up to doing that.

After Ruby told me this story I went through the newspapers of the day and actually found a slightly different account of what happened — that she had been robbed. This was a story that had not surfaced in any form previously, so the biographers who preceded me did not do thorough research. Much of the information on Bessie was there all along, waiting to be discovered.

JJM How did her volatile marriage to Jack Gee affect her career?

CA It affected her career because their marriage was such a roller coaster affair. When he was not there, she would go off the deep end and drink a lot, have parties involving sexual liaisons, and so forth. When he would suddenly appear — and he had a tendency to show up unexpectedly when they were on the road — she would sober up and wouldn’t even want to talk about parties and things. Her marriage gave her life a balance that it obviously needed. But he was so different from her. He never got used to show business, but he liked the money.

JJM This stability provided her with a reason to stay married to him…

CA Yes. He was the balance, and she needed that.

JJM Because he didn’t provide anything monetarily?

CA Absolutely not. And other than being there for her and providing her with some tenderness, he certainly did not contribute materially in any way. He took a lot, on the other hand, and it could almost be said that she bought that love. She would buy him expensive gifts, for example.

JJM She bought him a Cadillac at one time, paying five thousand dollars cash for it.

CA Yes, that was a lot of money for a car. You could buy a car for two hundred seventy dollars in those days, but this was a special show room model, and it was a Cadillac. She kept a carpenter’s apron under her skirt, always filled with lots of cash, and when she bought that car, she shocked the salesman by reaching under her skirt and coming out with a fistful of money. Ruby told me about that apron, and — after the first edition of the book was published, I found an interview with Louis Armstrong in which he also mentioned it. When they recorded “St. Louis Blues,” he asked to borrow one hundred dollars from her, and she surprised him by just dipping her hand under her apron and bringing out the money.

JJM Talk a little bit about their performance of “St. Louis Blues”…

CA Well, it is an extraordinary performance, because you have two of the most accomplished artists jazz has produced, and you have them playing together at the peak of their creativity. The result is that you have a great singer accompanied by a great trumpet player, but the result sounds more like a duet. Fortunately, Columbia recorded with good equipment, so the performance is well preserved. She did several recordings with Armstrong, although he was not her favorite trumpet player, Joe Smith was.

JJM How did the more refined styles of Ethel Waters and Josephine Baker affect the material Bessie Smith chose to perform?

CA I don’t know if the refined styles of those singers affected it at all. Even when Bessie did non-blues pieces like “After You’ve Gone,” it almost sounded like a blues, because she gave it that texture and that quality. Alberta Hunter and Ethel Waters were almost like chameleons — they could sing anything. Alberta’s London recordings from the early thirties with Jack Jackson’s Society Band included songs like “Two Cigarettes in the Dark” and “Miss Otis Regrets,” which are stylistically far removed from some of the early things she did with Armstrong, Bechet, and Clarence Williams. Towards the end of Bessie’s life, she started doing that, but it wasn’t because of Alberta Hunter or Ethel Waters or Josephine Baker, it was because times and tastes were changing. Bessie did well singing the blues long after the blues had been put to bed. But she realized that there came a time when even she would have to abandon the blues, and as the swing era of the thirties arrived, she started singing songs like “Tea for Two” and other popular songs of the day. Unfortunately, we don’t have any recordings of her doing that, but there are eyewitness accounts from people who say she did it very well, and I assume she did it with a little bit of a blues feeling.

JJM Did the improved recording technologies inspire any changes in her repertoire or in accompaniment?

CA In accompaniment, yes. Bessie did not like to record with drums, for instance, because the recording equipment did not handle drums very well, so in that way it did affect the accompaniment. But as you listen to Bessie’s recordings, you will see that it didn’t affect her music. Recordings affected all music because of the three-minute time limit. When performers like Bessie sang on stage, they didn’t limit their songs to three minutes, so in that way we have a slightly distorted impression of the music from the pre-LP era.

JJM Were her songs autobiographical?

CA I think almost every song was autobiographical. Honesty was a strength of hers, and it was one of the first things that grabbed me about her. She wasn’t just rendering words, she obviously put some feeling into them. When Bessie sang about a broken love affair, she certainly could relate to that, and the audience could sense that she wasn’t just singing them another song. She did a song called “Me and My Gin,” and another called “The Gin House Blues” that many writers deemed autobiographical, because she supposedly drank gin, but the truth is that she never drank gin. She didn’t even like gin.

JJM Yes, it was too high class and too high style for her.

CA Yes, Ruby said that Bessie would say that anything sealed made her sick, so she drank moonshine and what Ruby referred to as “bad liquor.” But at the time, blacks used gin as a generic term for hard liquor, so all hard liquor was called gin. And she didn’t write those songs either.

JJM She also sang bawdy material, “Kitchen Man” being an example.

CA There was a period there when blues was slipping in popularity, and Frank Walker, who recorded and produced all her recordings at Columbia, thought that if she started singing bawdy material, it would boost her sales. Consequently, during that time she sang “Kitchen Man” and another called “You’ve Got to Give Me Some,” but it didn’t do anything for sales.

JJM Another one she sang was called “I’m Wild About That Thing.”

CA Yes, which is basically the same song as “You’ve Got To Give Me Some,” but with different lyrics. Walker later recorded her singing some pseudo-religious songs with a gospel quartet behind her. While she did that well, it didn’t affect sales.

JJM A reporter for the Pittsburgh Courier wrote of a special 1924 Bessie Smith performance for a white only audience in Atlanta, “The program was greatly enjoyed by the white people who filled the house after the regular performance. According to the management, practically all seats in the house were taken for this special performance as early as Thursday morning. Miss Smith is a great favorite in Atlanta.” Why did her music appeal more to white Southerners than black Northerners?

CA Because the blues was a Southern thing. Whether you were white or black, when you grew up in the South, you grew up with the blues. The blues were a Southern, rural phenomenon. In the urban centers of the North, people felt that they had escaped psychologically from a life that would inspire the blues. When I first came to the United States in the late fifties, I got a job as a disc jockey at an all jazz station in Philadelphia. I played everything, from Ma Rainey to John Coltrane, and when I played the old recordings, whether it was the blues, or Clarence Williams or Armstrong’s Hot Fives, people would call and ask why I was playing “Mickey Mouse music.” Others called it “Uncle Tom music.” Some African Americans were discomforted by that, because it was something they related to a period of widely accepted discrimination against black people. One of the callers who called me regularly, by the way, was Bill Cosby. He used to call it “Uncle Tom music.” I only knew him as Bill until a couple of years later, when he had his first album out and I was working at WNEW in New York. He visited the station while promoting the record, and when we were introduced, he repeated my name and asked if I were the Chris Albertson who used to play the “Uncle Tom music” on WHAT.

JJM When did it occur to the record companies that black singers could be as marketable as white singers? Was this as a result of Bessie?

CA No, it was as a result of Mamie Smith. Mamie Smith was not a blues singer, per se, but she recorded a song called “Crazy Blues,” which was originally titled “Harlem Blues.” It was a gamble that Eli Oberstein of the Okeh Record Company took, and the market took them by surprise, because sales figures were high. The record industry assumed that black people didn’t own phonographs, which was the wrong assumption. Black people in fact did own them, and were buying opera recordings and whatever was available at the time. So as soon as there was something available that they could relate to more, they started buying it. That started the whole blues craze of the twenties, which is what brought Bessie into the mainstream.

JJM Yes, the first record she put out — featuring “Down Hearted Blues” and “Gulf Coast Blues” — sold eight hundred thousand copies, which is a quite remarkable number. She must have made a ton of money for her record company.

CA She absolutely did. They paid her more than they paid the other singers, including white singers — not that they paid very much, and of course they didn’t pay her any royalties.

JJM She just got paid, basically, for the recording performance itself.

CA Yes, not even for the performance. She got paid for each acceptable record. So, if she went into the studio and recorded six but only four were actually released, she got paid a flat fee for those four only. But it didn’t matter to people like Bessie, because she considered recordings to be a promotional tool. Artists did not look to recordings as a source of direct income.

JJM It was a way to promote her live performances…

CA Yes, to bring people to the theaters and to the tents.

JJM How did Bessie continue to succeed even in light of the decline of the blues?

CA Her voice. No one had that voice. It wasn’t just a commanding voice, she also had a commanding presence. There are some artists who don’t have to do anything other than walk out on stage to create electricity in the air, and Bessie was one of them. She never lost her voice, and she never lost her ability to use it. It didn’t really matter whether the song she sang was a blues tune or a Cole Porter song, it was Bessie. There was a Broadway show in 1929 called Pansy that wasn’t doing very well in rehearsals, so they hired Bessie to sing in it. She wasn’t part of the plot, she just came in between acts and sang a song. When the show opened, the reviews were universally devastating. One of the reviewers said it was as if the dancers were meeting each other for the first time on stage.

JJM Well, they were. Six performers never showed up…

CA That’s right. And Brooks Atkinson and all the top white critics reviewed this show, and they all agreed that the one saving feature of the show was Bessie Smith. Two of the reviewers mentioned that when Bessie finished singing, the audience just went crazy and seemed to desperately want to keep her on stage so the others wouldn’t come back.

JJM Columbia Records executive John Hammond seems to have contributed greatly to the myths of Bessie Smith. Hammond — via Paul Oliver’s 1959 biography of Smith — claims that Bessie was down on her luck when he met her, and that she had to sing “coon songs” and sell candy to survive. Is that true?

CA Absolutely not. John Hammond contributed a lot of the myths, but he was creating a myth around himself, so a lot of those myths he created around people like Bessie were by products of that one agenda. John had this image of the great white father. He had recorded Bessie, Billie Holiday, and as Benny Goodman’s brother-in-law, it was he who integrated the Goodman band, and so forth. When I came over from Europe, I definitely had the impression that John had probably done more to help black performers than any other white man. Then, sometimes after you get to know people and work with them, you see the truth. Not to say that John didn’t do a lot, because he did, but not as much as he wanted us to think. He was dictatorial, for one thing. He wanted to keep artists down where they were before, and did not like to see them advance stylistically. In fact, during World War II, Leonard Feather wrote an article about John Hammond the dictator in Metronome magazine. The article was entitled “Heil Hammond,” if you can imagine that. I actually saw that myself, and there were many artists who would have nothing to do with him. Lester Young, for example, absolutely refused to talk about him.

JJM It is hard to read some of his comments without a degree of cynicism. Following Smith’s death, for example, Hammond’s published claim that Bessie was refused care at the white hospital looked to be an effort to evoke sympathy for her that would ultimately lead to greater record sales.

CA Yes, and his story ended with a plug for Columbia Records’ reissue of her recordings. While Hammond did not invent the story of Bessie being refused care at a white hospital, he did publicize it. The whole story of her death never made sense to me. Why would an ambulance take Bessie to a white hospital where she would be turned away, when there was a black hospital within a half mile?

JJM To fill the readers in, she was riding in a car driven by her lover at the time, Richard Morgan, who rear-ended a truck that was parked along the side of the road.

CA Yes. Morgan — who was Lionel Hampton’s favorite uncle — was driving Bessie’s old Packard along Highway 61 in Mississippi. It was a very dark road, there were no lights on the truck, and they were upon it quickly. Morgan swerved in an attempt to avoid hitting the back of the truck, but couldn’t. Because Bessie’s elbow was out the window, the crash almost tore her arm off. The driver of the truck knew that something had hit him, but he kept going, driving right into Clarksdale. Right after this accident, Doctor Hugh Smith, who was on an early morning fishing trip with a friend, came upon the scene. Bessie was lying in the middle of the road, so the doctor had his friend go to a nearby house to call an ambulance. Knowing that Bessie was black, he naturally called the black hospital. In the meantime, the driver of the truck had stopped at the white hospital where he reported the accident up the road.

While all of this was going on, a small car carrying a young white couple came down the road and drove directly into the doctor’s car, pushing it against the wreck of Bessie’s Packard. So now there were three wrecked cars on the road. Subsequently two ambulances came, one from the white hospital and another from the black one. The white one took the couple, and the black one took Bessie. She had been bleeding very seriously internally, and they had to remove her arm. She never regained consciousness, and died around ten o’clock that morning. I interviewed Doctor Smith, who told me in great detail of Bessie’s condition. He said that even if the accident had happened right in front of a Memphis hospital — which was better equipped, of course, than those in Clarksdale — it is unlikely that she would have survived.

If there was a hint of racism in those days, the black press played it up. But there was no mention of racism when this accident was reported. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later, in a Down Beat article written by John Hammond, that racism was suggested to have played a role in Bessie’s death. Then all the press played it up and that is how this myth started. I asked John how he could make such a claim without first speaking to Richard Morgan or the doctors at the hospital about this, and he was sort of embarrassed about it.

JJM Well, the truth would have ruined his story.

CA Of course, that is what it is all about. Even when he wrote his autobiography a few years later, he invented another story to substantiate his fabricated story, which is amazing, but that is John Hammond.

JJM Are you satisfied now that the circumstances of her death have been properly sorted out?

CA Oh, absolutely, yes. I don’t think that there is any question. I found a letter at the Library of Congress written by the doctor at the black hospital who attended to Bessie that said she never regained consciousness, and that he had to amputate her arm, and the death certificate supports that. And he said that she was taken directly to his hospital, which by the way is now a small hotel called the Riverside Hotel. It is a tourist attraction which people come to from all over the world — mostly from Japan — to spend the night in the room Bessie died in.

JJM You wrote, “Bessie Smith became better known for the way in which she had allegedly died than for what she had done in life.” Do you still feel that way?

CA Yes, unfortunately, although I am hoping that my book will at least diminish the power of the myth of her death. The myth of her death was very well known because in 1959, the playwright Edward Albee wrote a play called The Death of Bessie Smith, which was based on Hammond’s account of her death. In that play resides the story of her being turned away from a white hospital, giving the myth some impetus.

As an aside, I was good friends at one time with well-known radical civil rights attorney named Flo Kennedy, who, among other things, handled the estates of Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday. But for about three years she didn’t speak to me. One night we happened to attend the same film screening, and I approached her about why she wouldn’t talk to me anymore. She replied by saying that I had no business printing that story about Bessie’s death. I told her it was the truth and she replied by saying she knew it was the truth, but that I had no business printing it! I think that was an attitude shared by some people, that I had ruined a good story.

JJM How did the civil rights movement and the emergence of the rock and roll era affect her legacy?

CA The civil rights movement brought an awareness of her music. Many of the people who used to call me on WHAT to complain about “Uncle Tom music,” realized that it wasn’t that at all. They began to understand the importance of the music. People no longer hid their gospel records when white people came to visit them. An awareness of the music’s importance began to take shape. Then the folk music renaissance began, and with it many of these blues singers were brought out of obscurity, and young people who had been listening to pseudo-folk music got into the real thing. I think that made a very big difference, as did the fact that Janis Joplin was totally into Bessie Smith. When I was working on Bessie’s LP reissue at Columbia, she used to come downstairs to the editing room just to listen to her.

When the book came out, there was renewed interest in Bessie, and somebody discovered that her grave was unmarked. A little campaign to raise money for a headstone was started by a Philadelphia paper, and Janis said she would pay for it. Simultaneously, another person, Juanita Green, a well-to-do black woman who owned several nursing homes, made the same offer, because she felt she owed her success to Bessie. They ended up sharing the cost. Ms. Green told me how when she was a little girl, she used to participate in a weekly children’s talent contest at the Standard Theater. One day, she came off stage, having participated in a talent contest, and saw Bessie standing in the wings. Bessie called her over and asked her if she was in school. When Junita answered yes, Bessie said, “You better stay there, because you sure can’t sing worth a damn!” She always remembered that.

JJM You write of her final recording in 1933, “Of course no one could have suspected it, but this was to be Bessie’s swan-song recording: the session affords us the only opportunity to hear Bessie with swing accompaniment, the flexible rhythm of a string bass, and a saxophonist who doesn’t sound like a refugee from a dance hall — a tantalizing hint of what might have come.” In your view, what would have come?

CA The Swing Era. Lionel Hampton was doing a series of small group recordings for RCA Victor at the time, and he told me he had planned to use her on some of them. By this time, she had changed her appearance. She stopped wearing wigs and swept her hair back, wore beautiful, plain evening gowns, and sang songs like “Tea for Two” and “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” During this time she performed at Connie’s Inn for twelve weeks, and many people heard her and saw that she had transformed herself. So, there is no question that, had she lived, she would have been a part of the Swing Era.

JJM Hammond claims that upon hearing Smith in 1927 it was the first time he realized there was more to jazz than instrumental improvisation. He said he was planning on recording her with Count Basie. Is that believable?

CA Knowing John, it is not totally believable, He would say things like that. I have been around John when people introduced him as the man who discovered Bessie Smith, and his way of dealing with that was to not deny it. But of course, when Bessie made her first recordings, John was ten years old. But that is how myths get started. If it sounded good to him and helped his career, he would let it be. On the other hand, he might well have had plans to record her with Basie, because he definitely was a fan of Bessie Smith’s.

JJM In his book, Early Jazz, Gunther Schuller calls Bessie Smith the first important jazz singer. Clearly she was moving in that direction…

CA Yes, although the first really important jazz singer was Louis Armstrong. But Bessie recorded vocals before he did. Some people make a distinction between the blues of Bessie Smith and the singing of Louis Armstrong. I think it is all just music.

.

.

___

.

.

.

Bessie

by Chris Albertson

.

.

About Chris Albertson

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

CA I don’t think I ever had one. I grew up in Iceland and Denmark, so I wasn’t exactly surrounded by the media. There was nothing really there to create a childhood hero for me. I think the closest person answering to the definition of a hero would be my maternal grandfather.

.

.

Chris Albertson is the acknowledged authority on Bessie Smith. A long-time contributor to Stereo Review, Down Beat, Saturday Review, and other publications, he has written extensive liner notes for jazz and blues albums and has produced a wide array of recordings, radio, and television programs.

.

.

.

This interview took place on September 22, 2003, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter (it’s free)

Click here to help support the ongoing publishing of Jerry Jazz Musician (thank you!)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.