.

.

In a 2002 Jerry Jazz Musician interview, NPR Weekend Edition host Scott Simon discusses his biography of Jackie Robinson, and the integration of major league baseball

.

.

___

.

.

Scott Simon,

author of

Jackie Robinson and the Integration of Baseball

.

.

___

.

.

…..The integration of baseball in 1947 had undeniable significance for the civil rights movement and American history. Thanks to Jackie Robinson, a barrier that had once been believed to be permanent was shattered — paving the way for scores of African Americans who wanted nothing more than to be granted the same rights as any other human being.*

…..In a 2002 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita, NPR Weekend Edition host Scott Simon, author of Jackie Robinson and the Integration of Baseball, discusses how Robinson’s heroism – and that of Dodger general manager Branch Rickey – got America to face the question of racial equality.

.

.

___

.

.

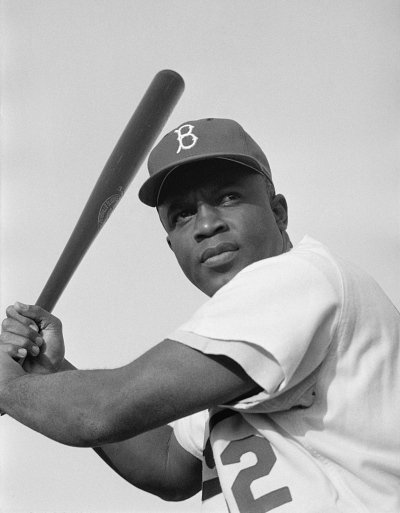

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Jackie Robinson, 1954

.

“I know that I have a certain responsibility to my race, but I’ve got to try not to feel that way about it because it would be too much of a strain…I also know that I’ve got to hit. I’m going to hit, all right, and I’m not going to worry at any time.”

– Jackie Robinson, 1947

.

.

JJM You wrote of Jackie Robinson, “When he was summoned by history, he risked his safety and sanity to give history the last full measure of his strength, nerve, perseverance. In the end, real heroes give us stories we use to reinforce our own lives.” How did Jackie Robinson touch your life prior to your writing of this book?

SS I believe he more or less touched all of our lives. Many of us grew up in a substantially better country because of what he did. I did not know a time when major league sports was not integrated, and that was just the first installment. I grew up during a time schools were integrated, and when job opportunities were much more ecumenical. None of this is to say that all of the important business has been done and certainly wasn’t when I was a youngster, but a lot of that can be, at least chronologically, traced to Jackie Robinson’s achievement in 1947. As I write in the book, when he stepped on to a major league baseball field in 1947, lynchings in the United States were commonplace. That is the environment into which he stepped. It is not just that schools are named for him that the story is known, or that his number has been retired on every major league team. It can be difficult to absolutely fathom the kind of every day routine adversity that he faced, and that is something that doing the book made me appreciate all over again.

JJM What is an example of Robinson’s heroism around the issue of race prior to baseball?

SS The most prominent example that stands out is when he refused to move to the back of the bus while at the Fort Hood, Texas, Army base, which was segregated at the time. A small-town-Texas bus driver reported Robinson to the authorities for sitting next to who he thought was a white woman. The woman, Virginia Jones, was in fact an African American woman who was married to a fellow officer in the African American unit at Fort Hood. It was the kind of prosecution Robinson could have easily avoided. He was in the right, undeniably, because the private bus carrier had agreed not to abide by local segregated statutes so that African American officers and enlisted men could get around easily. But Robinson chose not to duck that issue, even though he was arguably the best-known college athlete in the country. He chose not to stand on legalism. He chose to resist, and did so very energetically.

While a very thoughtful man, Jackie Robinson was an athlete. Like a lot of athletes who focus on their careers, I don’t think he had given a lot of larger social issues much of a thought for many years. What seemed to sharpen his awareness was the experience of his brother Mack, who was the sliver medalist in the 1936 Olympics, finishing right behind Jesse Owens. When he returned to the United States following the Games, Mack Robinson couldn’t get a job in Pasadena, California other than that of a garbage collector. While there is nothing wrong with being a garbage collector, it seemed to be the job in which he was relegated as opposed to one in he aspired toward and was qualified for. That probably sharpened Jackie Robinson’s idea of racial equity and equality of opportunity in the United States. It opened his eyes to the fact opportunity was denied because of race. Here he was, perhaps the most accomplished athlete in the nation, yet it was not possible to continue on in a career in athletics before he integrated the sport himself.

JJM When was having a black player in major league baseball first discussed by Brooklyn Dodger general manager Branch Rickey?

SS When it was first discussed by Rickey is difficult to say. During the early days of World War II, he had a substantially different idea about scouting. Most of the major league teams decided that the good players were in the Armed Services. As a result, it was not a time to spend much money on scouting. Rickey believed, on the contrary, that since other teams weren’t doing it, this was a time for the Brooklyn organization to step up its scouting opportunities. He knew that the largest source of unscouted and unsigned baseball talent in the hemisphere resided in the Negro Leagues and the Latin American Leagues, where a number of African American players were applying their trade. So, the two ideas were a companion in his mind. He decided that if anyone was going to break the stranglehold the Yankees seemed to have year after year of getting into and winning the World Series, he would have to find resources of talent that were being overlooked by the major league clubs.

There were obviously some very great players that were available in the Negro Leagues. He casually mentioned that he wanted to step up his scouting program to Brooklyn Trust, the people who held the note on the Dodger team, by way of suggesting that they were going to step up their scouting activities in the Latin American leagues. The bankers didn’t blanch at hearing that because scouting in the Latin American leagues was fairly inexpensive in those days. Then he said they were going to look at the Negro League as well. Perhaps because the Brooklyn Trust was made up of bankers who were already doing business with many African American families in Brooklyn, they didn’t blanch at that suggestion either. Branch Rickey remembered that one of the bankers said, “Why not? Maybe we will find somebody.”

JJM Was there some community or political pressure that helped accelerate the process of assimilating a black player into the league?

SS I am not sure “pressure” is the word because it is hard to figure out what exactly that pressure would have been. Political interest concerning this issue had been building up, really, at times dating back to the twenties. I will add parenthetically it seemed to be all around the political spectrum. The communist newspaper The Daily Worker had a very distinguished sports section. As I say in the book it’s a shame they weren’t as clear about Joe Stalin as they were about Joe DiMaggio. They had been one of the early editorialists concerning the issue of integrating baseball. On the other hand, so had right wing columnists, as well as an outspoken sports columnist like Shirley Povich, who was then writing in the very segregated city of Washington, D.C. The idea had been debated out there since the early twenties and seemed to gain over the years. In Boston, a city councillor named Isadore Muchnick proposed a law that would have prohibited the sale of liquor during Sunday ball games unless the Boston clubs at least gave a try out to a Negro League player. In fact, because of this, Jackie Robinson received a try out in Boston five months before he was signed by Branch Rickey and the Dodgers, but the Red Sox chose not to sign him, creating what I think is the true curse that has hung over their ball club ever since.

Near the end of his term, New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia said very explicitly that he thought it was wrong for him to be pressuring New York corporations, factories and industries to hire people of all races if major league baseball was a glaring contrary example to that. He talked very openly that if the major leagues didn’t take it upon themselves to integrate, he might try and ask the city council to pass laws to do so. So, it was important to Branch Rickey to be able to act before that law was passed, because, to be sure, he wanted credit for his place in history. He didn’t want it to seem as if it had been the politician’s idea.

JJM Abraham Lincoln was very important to Rickey. Was he motivated to create a legacy for himself that Lincoln would be proud of?

SS It was often observed that he had a picture of Lincoln hanging in his office. He was born just sixteen years after Lincoln had been assassinated, and grew up in southern Ohio among people who had very vivid memories of Lincoln the man, Lincoln the president, and of his funeral train as it passed through town on its way to Lincoln’s Springfield, Illinois burial ground. So, Lincoln was a hero to him. However, prior to his work with the Dodgers, Branch Rickey was the general manager of the St Louis Cardinals in the late thirties, and he made no attempt to integrate the game then. However, as I have often said, Lincoln wasn’t Lincoln all at once either.

I think there was a social and political component in this for Rickey. He was a man of large ambition. He didn’t believe baseball was just a game, he felt it was a game that made the country better. He felt he had an opportunity to help make the country better by integrating major league baseball in advance of other prominent institutions in the United States. First and foremost, he was a baseball man, and I don’t think he had to offer any apology for the fact that virtually the first words out of his mouth to Jackie Robinson were, “Jackie, I want to win a pennant for Brooklyn and I need the ballplayers to do it. Do you think you can do it?” There ultimately would have been something patronizing if all he wanted to do was integrate the sport for social reasons. He also understood that there was a potential championship waiting to be claimed by the organization with the nerve to integrate their team.

JJM He wanted to beat the damn Yankees!

SS Exactly.

JJM Did the greatness of pitcher Satchel Paige accelerate the integration of baseball?

SS I think in a way it absolutely did. Satchel Paige was the biggest draw in baseball — not Joe Dimaggio and not Ted Williams. He was the highest paid player in baseball, as well as being co-owner of the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues. Every newspaper in America was more or less writing about Satchel Paige in one way or another. If you were a baseball fan and hadn’t seen him play it was impossible not to be curious about what a good pitcher he was. People read accounts of exhibition games between the Negro League teams and major league stars, and from them knew Paige was the guy who struck out Babe Ruth and Joe Dimaggio. They understood what a great ballplayer he was. There were white players who counted themselves as bigots who were perfectly happy to play against Negro League teams for money, even if they weren’t all at once willing to play alongside Negro League stars as their teammates. The prominence of Satchel Paige made Negro League ball players, generally, more recognized in society and his stardom got people to notice the artificial separation that existed between a black league and a white league.

JJM One of the reasons Paige was not under consideration is because he was a pitcher and there was some concern about him throwing bean balls. With him out of the picture, how did they settle on Jackie Robinson?

SS It is important to say that there must have been 75 or more Negro League athletes who could have been signed and who would have succeeded brilliantly, but Jackie Robinson had the most desirable combination of circumstances. It was also possible for Branch Rickey to have brought up Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella at the same time to diffuse the attention and the burden, as well as the identity of Robinson’s achievement. That being said, he had the best possible combination of circumstances. As the best college running back in the nation, and perhaps the most versatile athlete, he had played under intense national scrutiny before. Baseball was arguably not even his best sport. He was a brilliant shooting guard in basketball, a great track star, a great football runner. He could have potentially even been an inter-collegiate golf champion if so many courses hadn’t been segregated at that point. So, he knew how to play under the scrutiny of national attention because he had done that in college.

The fact that Robinson was college educated was also appealing to Rickey because he understood the person he selected would be subjected to a great deal of national interest. Additionally, Robinson was a veteran. Rickey felt it was important that since so many American men and women served in the Armed Forces that the person he selected also be an Army veteran. Ironically, because he had been discharged from the Army in 1944, Jackie Robinson was available to be signed. There were other great Negro League athletes who had some of the same combination of talents and resume items as Robinson who were not available to play. For example, Monte Irvin of the Newark Eagles was still on duty in the Army in 1945, serving with the occupation forces in Germany. So, when Branch Rickey wanted to end the summer of 1945 by signing an African American ball player, Irvin wasn’t available. Irvin was also a college educated veteran who had many of the same qualifications Jackie Robinson did, he just didn’t happen to be available. As you mentioned, Robinson wasn’t a pitcher, so Rickey didn’t have to worry about signing somebody who threw the bean ball. Also, he was such a versatile athlete they didn’t have to worry about him only being capable of playing a specific position. They knew that he could play the outfield, the infield, or whatever position came open. He never played first base before yet they turned him into a first baseman, where he became an all star player. So, every possible qualification required seemed to lead back to Jackie Robinson.

JJM The fact that he was dishonorably discharged from the Army seemed to be a component of his resume that Rickey found attractive.

SS Yes, Rickey knew the story. Clyde Sukeforth, the man who scouted Jackie Robinson for the Dodgers, had made some careful inquiries and knew the story and thought it was terrific. Rickey was not in any way put off by his Army discharge, and in fact thought that the circumstances of it spoke well for the character of the man he wanted to sign.

JJM What was the immediate reaction in the Brooklyn community to Robinson being on the Dodger roster?

SS As a generalization, Brooklyn considered itself the most progressive territory in the United States at that point in time. It was politically and socially very liberal, and it was a community that was integrated in a larger sense, although often segregated block by block. They were PM magazine readers and Roosevelt lovers, and from Paul Robeson to Pistol Pete Reiser, Brooklyn loved “lefties.” In a way, the signing of Jackie Robinson called on Brooklyn to live up to its own best social and political convictions. It was also a distinction for Brooklyn, which was always a little conscious of being overlooked in contrast to Manhattan. They felt that, in a funny way, they were summoned by history to play a role, and to demonstrate something about themselves. For the most part they certainly lived up to that.

JJM Robinson was an instant sensation. While he experienced a couple of slumps early on, they were never enough to create tension about him staying with the club. What would Rickey have done, do you suppose, if Robinson failed as a player? Was there someone else waiting in the wings?

SS I have thought about that and I don’t know for sure. I think he was genuinely convinced that Robinson would not fail. As you note, although he had a brilliant minor league season, he began the season with a slump. Yet, Rickey knew that he was the type of player who could do so many other things for his team. For example, his base running was often so good that it kept him in the game and it still made him a factor in games even when he was going 0 for 4 and 0 for 5 at the plate. Rickey was convinced Robinson would succeed, and he was intent on assuring that by not pulling him when he slumped. When Robinson got into slumps later in his career, I think managers would not think much of benching him for a game or two, as you would any player, but Rickey wasn’t about to do that when he was starting his career, when it became known as the “great experiment.” If they had gone a few months without on field success, I don’t believe he would have sent Robinson to the minors, he may have brought up Roy Campanella, making the decision that the “experiment” was going to succeed even if it wasn’t with Robinson. He wasn’t going to totally bet on the one person who he thought was the best bet. I think he would have just kept trying until one player or another had broken through. As it happened, he didn’t have to worry about that.

JJM Larry Doby came up with the Indians of the American League in the same season…

SS Yes, he was signed in July by the Cleveland Indians, and they did not send him up through the minors. They brought him up directly from the Negro Leagues to the majors.

JJM Your chapter on Robinson’s experience in the minor leagues was very interesting. It’s easy to forget that he was also the first black minor league player affiliated with a major league franchise. The fact that he joined a team that had a Canadian city as its minor league property probably had a lot to do with the Dodgers being the first team to have a black player as well.

SS Yes, Boston often cited that that was the reason they couldn’t sign Jackie Robinson.

JJM Because Boston’s minor league team was in Louisville?

SS Yes, their farm club was in Louisville, although if Boston had been genuinely interested in signing Robinson there were other things that they could have done. I think the answer is that they were genuinely not interested in signing Robinson.

JJM They have had the wait and see approach to baseball for as long as I have been a fan of baseball, and as you say, not signing Robinson was probably a more damning curse than that of the Bambino.

SS I certainly think that. Obviously, baseball never should have been segregated, but if we get past that premise in which I deeply believe, this could have happened in Chicago, and probably should have. The White Sox should have signed a Negro League player. It certainly could have happened in any of the other teams in New York, and it could have happened in Detroit. It arguably could have happened in Washington, DC, the nation’s capitol, but it didn’t. It took the right combination of circumstances, including the community of Brooklyn and a general manager with a sense of history and the nerve of Branch Rickey.

JJM How did Jackie Robinson spend his life after baseball?

SS As I noted earlier, prior to his being a ballplayer, he had not spent much time worrying about social and political issues. But the process of becoming a national hero — a term I use adviseably — sharpened his conscience and his identity. He knew how important his story and achievements had become to so many people across the United States. Immediately after retiring he became a personnel executive for Chock Full O’ Nuts, where his specific mandate was to work on minority hiring. He also became a social and political activist. He supported the work of Martin Luther King, and he worked for Governor Nelson Rockefeller in New York. He was a very active liberal Republican at a time when people like Rockefeller, Ken Keating and Jacob Javits were in the Party. These men were real supporters of the civil rights movement, whereas the Democratic Party at the time was often typified by people like Strom Thurmond and Richard Russell of Georgia. So, he became a political activist. He wrote a column for the Harlem Voice and the Amsterdam News, endorsed political candidates, and supported Dr. King’s non-violent campaign for racial integration. He maintained himself as a factor in American life because he was so acclaimed as a hero, and understood that from that moment on, what he did, believed in, and endorsed were important to millions and millions of Americans.

.

.

___

.

.

Jackie Robinson and the Integration of Baseball

by

Scott Simon

.

.

___

.

.

.

.

This interview took place on December 18, 2002

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Pulitzer Prize winning author Diane McWhorter on Birmingham, Alabama and the events leading to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

.

.

* Text from publisher

.

.

.