.

.

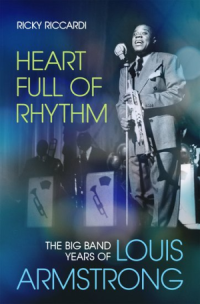

In a November 16, 2020 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician, Ricky Riccardi, author of Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong, discusses his vital book and Armstrong’s enormous and underappreciated achievements during the era he led his big band.

.

.

photo by Curtis Knapp

Ricky Riccardi, Director of Research Collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum, and author of Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong (Oxford)

.

___

.

…..To most jazz enthusiasts, Louis Armstrong’s greatest works are his mid-1920s Hot Fives and Hot Sevens sessions that resulted in historic recordings like “Cornet Chop Suey,” “Heebie Jeebies,” “Potato Head Blues,” “Weatherbird,” and, of course, the extraordinary “West End Blues,” on which Armstrong’s opening cadenza is considered a defining moment of early jazz. On these recordings, Armstrong invented the art of the jazz solo and set the stage for the way jazz would be performed and appreciated.

…..This work was so revered that it overshadowed the importance of much of Armstrong’s ensuing work, including the years in which he led a big band, 1929 – 1947. During this era, Armstrong was frequently heard on the radio and appeared in films, broke box-office records, published an autobiography, and even starred in a Broadway show. He became so popular with mass audiences of all races that it caused certain jazz writers to disparage him. One, the composer, conductor, historian and educator Gunther Schuller – though full of praise for Armstrong’s work in the 1920s – complained that Armstrong “did succumb to the sheer weight of his success and its attendant commercial pressures.” Another, Armstrong biographer James Lincoln Collier, lamented “the bitter waste of [Armstrong’s] astonishing talent over the last two-thirds of his career…I cannot think of another American artist who so failed his own talent.”

…..Other than a handful of critics who have defended the Armstrong of this era, this became the all-too- common storyline when evaluating Armstrong’s work. He “sold out,” he was a “showboat,” even an “Uncle Tom.”

…..Ricky Riccardi, Director of Research Collections for the Louis Armstrong House, is on a mission to help us better understand and appreciate Armstrong’s post-Hot Fives and Hot Sevens career. He did so ten years ago in his book What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years, and again in the remarkable Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong.

….. Riccardi writes: “Because many people only know his innovative recordings of the 1920s or the later hits of the All Stars era, Armstrong’s big band years are taken for granted. But it was in this 1929 – 1947 period that Armstrong influenced more musicians and listeners than at any other time in his life. He met popular music head-on, adapting the sounds favored by white listeners, and completely transformed them into something new, something exciting, something black, something swinging. Every trumpet solo seemed to contain enough ideas for scores of new compositions and arrangements. Every vocal was a personal statement, blowing up the way singers approached pop tunes forever more. Dozens of songs he recorded in this period became standards. His stagecraft, featuring daring displays of high note prowess and climax-building solos, had audiences screaming and cheering decades before rock ‘n’ roll. And he was funny, proud of his comic prowess and ability to make anyone, black or white, laugh.

…..“Yet this is the period that is ignored or misrepresented by so many in the jazz world. It was the jazz world that put pressure on Armstrong to break up the big band and form a small group – and then ditched him when the small group didn’t reflect the latest trends. But it didn’t matter. Armstrong was bigger than jazz.”

…..In a November 16, 2020 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Riccardi discusses his vital book and Armstrong’s enormous and underappreciated achievements during the era he led his big band.

.

.

_____

.

.

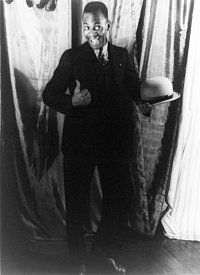

photo William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Louis Armstrong, Carnegie Hall, New York, N.Y., ca. Feb. 1947

Louis Armstrong, Carnegie Hall, New York, N.Y., ca. Feb. 1947

.

“This idea of a musician going ‘commercial’ is usually a dirty expression, but in Armstrong’s case I like to make the point that he blows up the pop world from the inside. Usually Black innovation is followed by white imitation – an example is Little Richard recording ‘Tutti Fruitti,’ followed up by Pat Boone singing the same song. In jazz there is the example of Benny Goodman becoming known as the ‘King of Swing’ even though Fletcher Henderson was swinging a decade earlier. So, this is the reverse, where you have these nasally crooners and moaning saxophones creating a bland pop sound, and Armstrong is then dropped into the middle of that, recording the same songs in the same month in the same year for the same record label. By the end of 1931, at the bottom of the Great Depression, he is the best selling artist in the country, in any genre of music, black or white, and that should not be taken lightly. Everything that follows – Bing Crosby, Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra – comes right out of these records.”

-Ricky Riccardi

.

.

Listen to a 1933 recording of Louis Armstrong performing “I’ve Got the World on a String”

.

.

JJM What is your role at the Louis Armstrong House Museum?

RR My title is Director of Research Collections, which is a fancy way of saying “Archivist.” I have been there for eleven years, and it is just a dream job because I am pretty much the gatekeeper to the archives. The actual Louis Armstrong House Museum is our main program – people come from all over the world to take a tour of Louis’s home, which is a National Historic Landmark. Queens College is where the historic archives live, and the core collection is Louis’s stuff – his trumpets, his tapes, his scrapbooks – but we have added 12 other collections over the years, and all those collections are my domain.

Before the pandemic I would be busy hosting events like school visits, and trumpet players would come by to play the trumpets, but since receiving a 2.7 million dollar grant in 2016 from Robert F. Smith and the Fund II Foundation to digitize the entire collection, I have been able to stay, arguably, busier than ever. While I am sitting at home, the entire archives are now in the Cloud, so if I need to get a manuscript page or find a photograph or scrapbook, it is just a click away. So, it’s pretty surreal, and I don’t think I am qualified to do anything else!

JJM When you interact with guests at the Museum or anyplace within your work, what is the biggest misconception they have of Louis Armstrong?

RR It is people unwilling to take him at face value. They see him, they watch him perform, they hear the music, and they are always trying to get at something. They enjoy his music and it makes them feel good, but they question what is really going on here because there’s no way he could possibly be that happy. He must have hated his manager, he must have been tormented by fans, he must have known these songs were stupid and these commercial and film roles were so beneath him. So they start going down that tragic path of making Louis Armstrong an example of what happens when you are a great African American genius and you totally surrender to commercialism and record tunes like “Hello Dolly” and “High Society Calypso.” He is then perceived to be an innovator who made bad choices and traded it all away, which is something that has gone on since the 1930s, starting when he was about 32 years old.

Armstrong in full costume as Bottom during the “Pyramus and Thisbe” sequence of the short-lived Broadway production, Swingin’ the Dream in 1939.

Pushing back against that is what I am here for. In both of my books – and pretty much my daily existence – I try to get people to realize that the man was a genius when he was born, he was a genius when he died, and everything he did is worth listening to and worth accepting on its own. Of course it is not all the same level of greatness, but he is there to be studied. He left behind these archives, he left behind these private tapes, and he wrote about his life constantly.

It’s a funny thing, I have spent about 25 of my 40 years on Earth devoted to him, and the deeper I dig the more I realize the truth is all on the surface level. What you see is what you get. Could he be angry? Could he be volatile? Could he hold a grudge? Could he curse up a blue streak? Yes, he is a human being, but this is a man who figured out life early on, and he was just so down to earth and so approachable, never letting his fame go to his head. He was also hell-bent on integration, which was a big thing for him, starting in the 1920s and moving on throughout his career.

He had a totally corny taste in music, so he loved Guy Lombardo and he loved the silliest things that made jazz purists want to vomit, but he legitimately liked that stuff. It’s a funny thing, you study and study and read and read and learn and learn and then you realize that it was all there the whole time. I quote both Jaki Byard and Miles Davis early on in the book about how natural Louis Armstrong was, and that’s the thing I would love for people to accept, that this man was so comfortable in his own skin, and so confident, and everything he did on and off stage, the way he talked to people, the way he carried himself – he was proud, he was dignified, he was funny, and he was aware of all of it.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to a 1931 performance of Louis Armstrong playing “Stardust”

.

JJM What were some of Armstrong’s personal goals during this 1929 – 1947 period your book focuses on?

RR His personal goals were very simple. One goal is that he wanted to please himself – he would always say that he was his own audience – so the music he made had to meet his standards. Another goal was to be sure that all his bills were paid and that he had food to eat. If he accomplished that, everything else was gravy. He never set out to be the world’s greatest trumpeter, to make a million dollars, or to carry his race on his back and break down these barriers. All those things happened, but they were never his goals.

When you read his autobiography, Satchmo, My Life in New Orleans, it ends with him joining King Oliver in Chicago, and having that feeling of leaving home, making money in a big city, and making it. Everything that followed in the last fifty years of his life – things like knocking the Beatles off the charts, stopping a war in the Congo, and starring in Hollywood films – was all gravy.

JJM There have been several biographies written about Armstrong. Did you have access to primary source material that previous biographers did not?

RR Yes, and that was a goal with this book. I know those previous biographies backwards and forwards, whether it is Terry Teachout, Thomas Brothers, James Lincoln Collier, Max Jones, Lawrence Bergreen, or Gary Giddins. Reading their work on Armstrong is how I got into this music. But I didn’t want to consult any of those books while writing mine. I wanted all the research to be primary sourced.

One of things that has happened in recent years that perhaps other biographers didn’t have access to is an incredible digital landscape, which allows you to sign on to your computer and, without ever leaving your home, access every issue of publications like Billboard and Variety, you can comb the Black press and every newspaper in every little town and county and search for Louis Armstrong and read how he was covered. I leaned heavily on that kind of stuff, and for most of it I didn’t even have to move. Also, all of the materials within the Armstrong Archives has been digitized and available for research.

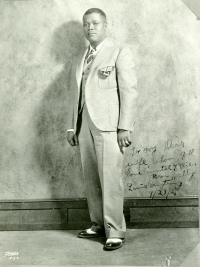

This publicity photo from 1929–which Armstrong referred to as his “movie star pose”–was inscribed from Louis to Lil, “To my Dear wife, whom I’ll love until I die. From Hubby, Louis Armstrong. 9/23/29.”

Louis also left behind about 700 reel to reel tapes, and I am probably one of only two people who listened to every one of those tapes – the other being Armstrong himself. Other researchers have listened to the “Best of” the tapes, consisting of 10, 20 or 30 tapes. I have also gone through all of his scrapbooks, and after receiving a grant to do research at the Institute of Jazz Studies, listened to the oral histories of Charlie Holmes, Bill Coleman, Pops Foster and the musicians who were there.

So the goal was to fall back on Louis, the musicians and writers of his time, and to try to avoid too much 21st Century theorizing. I wanted to cover it the way it went down – how did the Black press cover him? How did the musicians feel about him? How did the jazz press cover him? If I wrote this book ten years ago it might have been different because I would have been working with the same sources previous biographers used, but the fact that everything has opened up digitally just gave me a whole new world to plug into.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Armstrong’s 1938 version of “Struttin’ With Some Barbeque”

.

JJM You wrote, “Armstrong was much more than a jazz musician; he was a popular artist and entertainer who appealed not just to jazz aficionados, but rather to anyone who regularly listened to music and liked to have a good time. If you were hip, you loved Louis Armstrong. If you were square, you loved Louis Armstrong. He ultimately transcended the world of jazz – and for that, the jazz world never truly forgave him.” What do you hope your book will accomplish others have not?

RR The book is just one in a long line of things I’ve been doing for about a decade, which is to get people to appreciate Armstrong’s total output, to put his work into context, and to understand what he accomplished – all with the hopes of broadening their minds about him a bit.

Jazz education students are primarily taught about Armstrong’s work from 1928 and prior – for example, the cadenza on “West End Blues” and the perfectly constructed solo on “Potato Head Blues” – but it is rare that the education goes beyond that. This is something that has been going on for fifty years now. The musician and historian Gunther Schuller wrote in his groundbreaking 1968 book Early Jazz that Armstrong, towards the end of his career, “did succumb to the sheer weight of his success and its attendant commercial pressures,” and that “he now wanted to enjoy the returns.” When the Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz comes out in 1973, the critic and collection producer Martin Williams includes only one track after 1931 – “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues” – and nothing after that. I always make sure to let people know that I am not the only one who appreciates Armstrong’s work of this era – Dan Morgenstern, Gary Giddins, and the late Stanley Crouch are among the people who have argued about the importance of Armstrong’s total career – but it seems like jazz critics and educators don’t know what to do with him.

Riccardi’s 2011 book, What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years (Pantheon)

I got into this world wanting people to take Armstrong’s All Stars years more seriously, because I felt those years have had a bad track record – so many people would say things like the hits are cringey, or that the band plays the same solos every night. My first book, What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years (2011), was my attempt to get people to slow down, listen to this music, and discover what he accomplished. I do think the later years are in better shape now than they have been in a while – there are more reissues, there are more young musicians forming All Star tribute bands and performing in All Star tribute concerts.

Last year I went to New Orleans, where some of that city’s finest musicians put together an all-star big band. I brought down arrangements from Armstrong’s big band book from the archives for them to play. One of them was “Struttin’ With Some Barbeque,” which was recorded for Decca in January of 1938 and was one of Maynard Ferguson’s and Bobby Hackett’s favorite Armstrong records, yet here were 16 of the finest musicians in the city of New Orleans – most of them probably younger than 40 – and they didn’t even know that record. When they played the first unison break they all kind of laughed about how hip it was, it was like a laugh of wonder. I had to get my phone out and play the record for them over the loudspeaker, and everyone’s jaws hit the ground. By that point I was already working on this book but I was clear that that was the goal now – that people need to listen to these Okeh’s and these RCA’s and these Decca’s and just marvel at what he is doing with both horn and voice, and in a variety of settings. Listen to him with a Hawaiian band, listen to him with the Mills Brothers, listen to him with a big band, listen to him singing spirituals with a chorus. So, that’s the goal. I will never say anything disparaging about the Hot Fives and the Hot Sevens – everybody should know those backwards and forwards – but his career is much more than that.

.

A musical interlude…the 1929 recording of Armstrong performing “When You’re Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With You)”

.

JJM You describe his manager at the time, Tommy Rockwell, as the “second great architect of Armstrong’s career,” the first being Lil Hardin Armstrong. What was Rockwell’s vision for Armstrong?

RR Rockwell realized that the Hot Fives were selling well, but he also knew that this music was never going to achieve pop status. For one thing, they recorded on the “race” label Okeh, and also the trumpet, trombone, clarinet, banjo makeup of the band was not the sound of 1928. At the time, America was listening to Cliff Edwards, Guy Lombardo, and Paul Whiteman, so Rockwell’s idea was to get Armstrong off Okeh’s “race” series and get him on their “pop” series, and the way to do that was to break up the Hot Five setup, give him a big band inspired by Lombardo, and have him record the same songs all the white artists were playing. Right out of the gate is this run of great songs like “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “When You’re Smiling,” and then the songs we now consider to be in the Great American Songbook – “Stardust,” “Body and Soul,” “All of Me” – songs that keep getting played today. Every time Armstrong records one of these songs, it becomes the definitive version. That is because of Rockwell.

Courtesy of the Louis Armstrong House Museum

Armstrong signs the historic contract to host the Fleischmann’s Yeast Show on radio, flanked by two of the most important managers of his career, Joe Glaser on the left and Tommy Rockwell on the right.

This idea of a musician going “commercial” is usually a dirty expression, but in Armstrong’s case I like to make the point that he blows up the pop world from the inside. Usually black innovation is followed by white imitation – an example is Little Richard recording “Tutti Fruitti,” followed up by Pat Boone singing the same song. In jazz there is the example of Benny Goodman becoming known as the “King of Swing” even though Fletcher Henderson was swinging a decade earlier. So, this is the reverse, where you have these nasally crooners and moaning saxophones creating a bland pop sound, and Armstrong is then dropped into the middle of that, recording the same songs in the same month in the same year for the same record label. By the end of 1931, at the bottom of the Great Depression, he is the best selling artist in the country, in any genre of music, black or white, and that should not be taken lightly. Everything that follows – Bing Crosby, Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra – comes right out of these records.

JJM You write effectively in the book about the importance of Armstrong’s comic genius, not just as a performer but also as a recording artist. Who were his comic influences?

RR The two biggest ones are Bert Williams and Bill Robinson. He wrote about remembering the first time he heard a record as a kid, which was Williams’ “Somebody.” He heard it on the streets in New Orleans, and it just knocked him out. When he was a teenager he was even doing Bert Williams routines in his mother’s church.

Bert Williams, c. 1921

.

Library of Congress/Carl Van Vechten Collection

Bill Robinson, 1933

The fact that he is a “ham” is a big part of Armstrong, and people shudder at the comedy and wonder why this great genius would lower himself to telling off-color jokes, but he never viewed it that way. From his childhood, Armstrong was a born ham, and he loved to make people laugh. There is a story of him going to the Iroquois Theater in New Orleans and winning an amateur night contest doing a routine in white face, covering his face in flour. And even when he joins King Oliver and Fletcher Henderson, they won’t let him sing, which is fascinating, but they both let him do his preacher routine, which the audiences loved. News clippings in Chicago show that was still doing it with Erskine Tate’s band. The humor is there in the Hot Five and Hot Sevens recordings as well. The record company would usually cherry pick the instrumentals – whether it’s “Cornet Chop Suey” or “Potato Head Blues” or the scat features like “Hotter Than That” – but if you listen to “Big Fat Mama” or “Skinny Pa” or “King of the Zulus” or “Irish Black Bottom,” or the monologue on “Monday Date,” the comedy is all there.

Then, when he sees Bill Robinson in Chicago in 1922 on stage for the first time it becomes a life changing moment because he had never seen an African American dressed so sharply and in total command – the dancing was virtuosic, and the humor had Armstrong laughing so hard that the bassist Bill Johnson, who brought him to the show, almost had to take him out because everybody was looking at him.

Armstrong wasn’t a tortured artist being forced to do comedy to make ends meet. He was a guy who in his spare time was writing joke books and hanging out with African American comedians, writing comedy routines, seeing who could top each other, mugging and giving each other nicknames, so comedy is a big part of Louis Armstrong. You may not find it funny in 2020, and you don’t even have to laugh, but the trumpet playing, the singing, and the comedy is part of his total entertainment package.

.

A video interlude…Watch Louis Armstrong perform “Skeletons in the Closet,” from the 1936 film Pennies From Heaven

.

JJM The comedy was controversial, not only to the jazz critics but to audiences in the Black community as well. The cultural critic Gerald Early said that Armstrong’s stage presence “made a lot of black people uncomfortable,” causing him to lose support among Black Americans. When did blowback from the Black community begin? Did his comedy routines contribute to this blowback?

RR It’s later than you would think. The seeds of it came from his role in Pennies From Heaven, which literally inspired a debate in the Black press. This was a major moment for Armstrong – he became the first African American to get featured billing in an otherwise white Hollywood film – but it included one comedic scene where he doesn’t know how to divide ten percent among his seven musicians, so he asks for seven percent instead. To Armstrong, that was the funniest damn thing in the world. We have letters in which he recounted that scene, and he also talked about it on at least two reel-to-reel tapes. He appeared on The David Frost Show in 1971 with Bing Crosby and did the entire routine from memory.

While he thought it was great and got the biggest laugh in the picture, the Black press thought otherwise. While acknowledging that Armstrong appearing in the film was a big deal, the New York Age asked why he had to take the role of a chicken thief, and he should realize that we are trying to make progress and that moments like this are holding us back. On the other hand there are people who felt otherwise. Alfred Duckett, who became one of Martin Luther King’s speech writers, thought it was just a comedic role in which Armstrong was funny and should be applauded for. So the seeds for this blowback are there, but the Black press was overwhelmingly in Armstrong’s corner.

The Jack Bradley Collection, Louis Armstrong House Museum

Shortly before filming his role in Going Places, Armstrong wrote to a friend, “I love to do Comedy for those Picture Stars.” He was widely praised for his comic work in the film, but many in the black community felt the role was too demeaning and offensive.

The change really happened in the 1950s when the civil rights era gathers steam, and I point to three things. The first is that Armstrong breaks up the big band and forms the All Stars, which the jazz press applauded initially because they saw him as returning to his New Orleans roots, but that trumpet, trombone, clarinet thing didn’t fly with Black audiences. The Apollo stopped booking him in the early 1950s because there was no audience for “Dixieland Bands” in Harlem. The second is that in 1949 he is “King of the Zulus,” which is a very African American-centric tradition, but pictures of him in blackface show up in all the newspapers, and that really hurt him. The third is in 1951, when he recorded “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” and sang the word “darkies.” After that, the Black press was talking about boycotts and people in Harlem were smashing his records, but because of actions like speaking out against the governor of Arkansas in 1957 for refusing to desegregate the schools, I don’t think he completely lost the support of African Americans.

On May 9, 1964, Armstrong’s recording of “Hello Dolly” became the #1 single on Billboard’s charts, ending The Beatles’ 14-week run of #1 songs

.

Louis Armstrong and His Friends was Armstrong’s next-to-last recording

I do think younger African Americans – those who grew up with Ray Charles and Sam Cooke and James Brown – saw Armstrong in the 1960’s sing “Hello Dolly” and “Mame” and thought that this guy was past his prime. It is an interesting thing, however, because he does have this last hurrah in 1970/71, when he records the album Louis Armstrong and Friends and sings “We Shall Overcome,” on which Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman are in the choir, and he also appeared on the Flip Wilson Show, which was the hippest thing with Black audiences at that time. And if you watch any coverage of Armstrong’s funeral, the people who came to Queens to view his body were 98% African American. They knew his importance. So his relationship with the African American community was complex, but a lot of people were in his corner until the end.

JJM Another key figure in Armstrong’s life was his manager after Rockwell, Johnny Collins. How did Collins see advancing Armstrong’s career?

Courtesy of the Louis Armstrong House Museum

Armstrong poses with Johnny Collins and one of his first Selmer trumpets in this photograph from c. 1933. Note Armstrong’s later annotation describing Collins as his “Ex Manager.”

RR Johnny Collins is a shady, awful figure, but he was the right man for the right time. With Collins at the helm, Armstrong’s Okeh records really do explode, he appears in movies for the first time, is on the cover of Time magazine, performs in Europe, and makes more money than he knows what to do with. For those reasons the Collins years are incredibly important. In three years’ time, Armstrong went from an artist trying to make a name for himself in California to being an international star. He has Collins to thank for that.

But Armstrong had to live in constant fear during those three years, with gangsters hounding him, extortion threats, being held at gunpoint, needing to leave New York and then Chicago, and traveling with bodyguards. This is quite a hectic period for Armstrong, which is why he brought Joe Glaser in to make all that go away, allowing Armstrong to finally breathe a sigh of relief.

JJM What was Glaser’s strategy for Armstrong?

RR Glaser’s background, as we know, is “sketchy,” and that doesn’t come close to covering it. He was involved with whorehouses and gangsters and bootlegging and used cars and rape allegations, so this is not a good guy in his early days. But Armstrong remembered that when he played Glaser’s Sunset Café in 1926/27, Glaser billed him as “the World’s Greatest Trumpeter.” He watched how Glaser operated. He knew that he needed protection and he knew he needed a white manager, and that guy wasn’t going to be Rockwell, who had already tried to extort him, and it wasn’t going to be Johnny Collins, who called him the “n” word and who was threatening to sue him.

So Armstrong is at his rock bottom – underground for about six months with no band, no recording contract, no lip, and he is being sued – when he finds Joe Glaser, who is out of money due to the Depression, and also at the end of his rope. Armstrong hires Glaser and tells him that he just wants to play the horn, and gives him the responsibility of paying Armstrong every week, of hiring and firing the musicians, and for booking the band. Glaser does all of that, and as Armstrong’s manager his approach was to have him pretty much conquer every form of media that he could. There are all of his records, of course, but he also gets Armstrong on Broadway in a major revue at Connie’s Inn, he gets him on the radio – starting on Walter Winchell’s show but also broadcasting on CBS twice a week – and he gets him a book deal. When swing music is blowing up Armstrong becomes the first African American musician to write an autobiography, Swing That Music. Glaser also gets him into the movies. All of this is happening in a short period of time. In the summer of 1935, Armstrong is at the bottom, but by the summer of 1936 he is on the charts with his Decca recordings and in Hollywood filming Pennies From Heaven, so Glaser becomes this figure in Armstrong’s life that you could never criticize in front of him.

Glaser is the type of figure who rubs people the wrong way, and I don’t turn him into a saint in the book – I do the opposite of that – but I also make the point that the relationship worked. It was not the stereotypical arrangement of the white gangster making all the money while the Black genius works hard and goes broke – they both ended up millionaires. If Armstrong felt like he was not being treated fairly he could call up Glaser and cuss him out, threaten to retire, and do whatever he wanted. Glaser made sure that Armstrong had total piece of mind, total protection, could hang out and smoke marijuana and basically do whatever he wanted off stage. For all intents and purposes they were the right match. It was the kind of relationship that makes our 21st century sensibilities cringe a little, and it wasn’t a pretty relationship, but it worked for both of them. For the last 36 years of Armstrong’s life he got to live in complete piece of mind and just worry about the trumpet – no more gangsters waiting in his dressing room, no more being held at gunpoint, no more bodyguards. Glaser is the crucial figure in Armstrong’s life during this period.

JJM The famed newspaper columnist and radio commentator Walter Winchell was a big supporter of Armstrong’s, but he also seemed to be a major contributor to his challenges…

By ABC Television/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

Walter Winchell

RR Yes, Winchell’s influence was massive. Anytime he mentioned Armstrong the Black press would write about it, and Armstrong would cut out the clipping and put it in his scrapbook. Winchell was a key tastemaker in this period – he supported Armstrong, he was there at the Apollo, and he had him on his radio show when he came back from Europe. So, all of that is good, but in 1942, when Armstrong and his wife Alpha hit the skids, he wrote to Winchell about how Alpha cheated on him, who she cheated with, and how when Louis runs into that guy he is going to shake his hand and thank him. Winchell published almost the entire letter, calling it something like “The Diary of a New York Love Story,” and it created a big buzz. Many people in the Black press were uncomfortable with that, but Armstrong believed that any publicity is good publicity “as long as they spell my name right.”

This inspires him to write letters to Winchell regularly, and Winchell starts publishing them regularly. The problem is that Winchell, who was a product of his times, edits Armstrong’s letters in the most painful dialect. Armstrong always used slang and jokes, but these letters are unlike anything that survives – Winchell basically turns them into the words of a minstrel character – and the Black press notices and asks Armstrong to stop writing to Winchell because his letters are embarrassing. But one of the letters we have at the Archives is a letter from Armstrong to Winchell, thanking him for the publicity, reminding him about how he has always been in his corner. It is one of the few times that Armstrong is not reading the room correctly. Those letters definitely hurt his standing with the Black community, even if it raised his profile in terms of publicity.

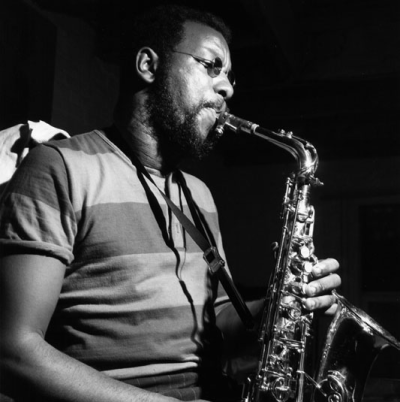

JJM There is so much going on at this time. While Armstrong is breaking artistic barriers at a time of high racial tension, it also creates a climate for other Black artists to do so as well. This creates more opportunities as well as complexity for the music, and for Armstrong personally. For example, concerning Coleman Hawkins’ landmark 1939 recording of “Body and Soul” – one of the earliest recorded examples of bebop – you write, “To a supporter of jazz as a harmonically daring, constantly evolving, improvising music, the big swing bands, black and white, suddenly seemed a little too stagnant and commercial compared to what Hawkins was playing.” In that climate, Armstrong really had some challenges with the jazz critics. What were their expectations of Armstrong as the Swing Era was ending?

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Coleman Hawkins’ 1939 recording of “Body and Soul”

.

RR As the Swing Era was ending, the main jazz voices out there – critics like Leonard Feather and John Hammond – were of the opinion that Armstrong needed to return to the “sincerity of the 1920s.” That was really it. They viewed Armstrong’s big band and the recordings he made for Decca as being totally out of touch, but that was just the jazz world, and that’s where this disconnect is.

I write about this quite a bit in the book because African American audiences loved Guy Lombardo, and when Andy Kirk’s band made it big it was because of Pha Terrell’s vocal of “Until the Real Thing Comes Along,” not because of Mary Lou Williams’ arrangements. So there was always a heavy segment of the African American community that wanted to hear the melody, love songs, and “commercial music,” and Louis Armstrong dispensed that. Whatever he recorded was very appealing to mass audiences. The stuff he was doing on the trumpet was unbelievable – he made it sound so easy – his vocals were beautiful, he is doing his own thing, and he had a big audience. He knew what he was doing.

There is quite a contrast between Armstrong and Hawkins at this time. Hawkins is the definition of what most people would consider a jazz musician because he improvised all the time, never looked backwards, and was comfortable playing with Sonny Rollins or Red Allen, recording with the boppers and encouraging new sounds. And Hawkins wasn’t a showman – he didn’t sing and he barely even smiled. He was writing the book about what it meant to be a jazz musician. Meanwhile, Armstrong is appearing in movies and on the radio, writing books and singing “La Cucaracha” – he is a different specimen. I am sure Armstrong admired Hawkins’ “Body and Soul,” but I don’t think he had any desire to do that. To him, especially in this late Swing Era time frame, it is all about him keeping up with the times, moving along with the trends. Luis Russell’s band got a little ragged so he brought in Joe Garland. He is recording tunes like “Leap Frog” because he knew it would be popular in juke boxes and with Black audiences.

All of this is happening at a time when the Hot Fives records of the 1920s are reissued by Columbia, which is when the jazz world loses its patience because people like Leonard Feather and John Hammond were writing about them for years, and now, after World War II, those records were everywhere and they are being reviewed along with all of the new releases. It’s a funny thing because most of the regular music critics in your mom and pop towns are finding the records a little corny, but the jazz critics saw them as the height of innovation and felt he needed to go back to that.

photo William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Jack Teagarden, Dick Carey, Louis Armstrong, Bobby Hackett, Peanuts Hucko, Bob Haggart, and Sid Catlett, Town Hall, New York, N.Y., ca. July 1947

For Armstrong, this is all about survival. One camp wants him to go back to New Orleans, to go back to the Hot Five, and there is also the audience who is encouraging him to keep doing what he is doing. But then modern jazz breaks out, the “moldy figs” become vocal, rhythm and blues break out, Sinatra and other crooners break out, and Armstrong is in the middle of all of this. He was at a crossroads, and which road is he going to choose? He ends up picking a path, the All Stars, that checks all of the boxes, which was an ingenious way to survive, and while it becomes the most profitable and popular period of his life, it pretty much angers all of those groups. He loses Black fans, the critics think the All Stars are too show biz, and the “moldy figs” think it’s too modern, and the modern folks think it is too old-fashioned. So all of those people can’t get on board, but the All Stars proved to be the right move for his career at that point.

JJM One of the first performances of the All Stars was at Billy Berg’s in Hollywood, and critics had a lot of good things to say about that. But that was short-lived once he dissed Dizzy Gillespie and bebop, igniting the “jazz wars”…

RR Yes, it’s a funny thing because the statements he makes on bebop that really explode are given to Time magazine during the Billy Berg engagement, and things had been brewing for awhile in that direction. You can analyze all of Armstrong’s statements and find that he actually compliments bop in the Esquire jazz book of 1947, and he records “Snafu” with Neal Hefti and the Esquire band which is bop-ish if not bop, and he hires Dexter Gordon and Kenny Clarke and Charles Mingus, but those jazz wars were just so cruel.

Courtesy of the Louis Armstrong House Museum

From left to right: Dizzy Gillespie, unidentified, Louis Armstrong, Arvell Shaw and Big Sid Catlett share a laugh at a nightclub in the late 1940s.

By this time Leonard Feather was really stoking the flame. In general, musicians would treat Armstrong like a god, but you would start to see quotes from Dizzy and other contemporaries of Armstrong sometimes slamming him by name, and other times creating an anti-New Orleans, anti-Bunk Johnson narrative, and I think Armstrong took that personally. Dizzy actually makes the first jabs during his Downbeat blindfold test with Feather, where he gives one of Armstrong’s records one star and he criticizes it from top to bottom. Armstrong keeps his mouth quiet, but then his performance at Billy Berg’s is such a triumph and I think he just needed to unburden himself. What he says makes a lot of people cringe, but at the same time there are some kernels of truth in there. As an example, he says that bebop is made by musicians for other musicians, and that while he could listen to it and enjoy it, it was not music for the untrained ear or for the masses. We have his record collection at the Archives – it includes Dizzy records, Bird with strings, Clifford Brown, Miles Davis – so we know he could appreciate it but he knew that wasn’t the music that was going to keep musicians working and move jazz ahead.

So he had the triumph of his career at Billy Berg’s and then just unloads about bop, and that’s when the war begins and when he starts to lose his standing in the jazz community. Imagine if you were a young, hip musician coming up during this period, reading Leonard Feather’s “Blindfold Test,” and in the midst of this is this “old man” of 46 bashing this new music. Then, Dizzy fights back and calls him things like a “plantation character,” making Armstrong appear out of date. A lot of those young musicians end up becoming the jazz educators of the 1960s and 70s, and some of them probably never quite got over that. I still get it today. I will meet young musicians and talk about how great Armstrong was and they will respond by saying, “Sure, but he didn’t like bebop.” In many ways that is Armstrong’s cardinal sin. In a lot of jazz history and jazz education, jazz begins with bebop, and the fact that Armstrong didn’t play it – and even knocked it – to this day a lot of people can’t rectify that.

JJM What is known about Armstrong’s time in Paris, when he lived there in the second half of 1934? Who did he hang out with? Where did he live?

Armstrong spent the second half of 1934 living in France, taking time here to pose in front of a Metro station in Montmarte.

RR I know he spent a lot of time with Bricktop, and he heard Django Reinhardt for the first time. The critic and jazz impresario Hugues Panassie was one of his biggest supporters so I know they spent time together. He lived at the Hôtel Alba Opéra, which has a plaque honoring him on the façade of the building. Mostly I think that when he lived there he was burned out and exhausted and just cooling it.

An interesting thing to point out is that when he came back to America he may have felt that he was behind the times. Benny Goodman had started to explode, Downbeat magazine is in production, and Armstrong doesn’t even have a lip – he’s hanging out in Chicago, begging for scraps. So for the rest of his life he made a point of saying that while Europe is great, if you spend too much time there the people in America will forget about you. He understood that many musicians would go over there and stay over there to get away from racial strife and just relax, but the scene was in the States and he needed to be a part of that.

JJM Armstrong’s music is interesting to talk about from a musical standpoint, but also sociologically, which you do so well in the book. I am going to name a few songs he recorded and ask you to provide some biographical details for each, and the first is “Knockin’ A Jug.”

RR “Knockin A Jug” represents integration, which is a big thing for Armstrong. This is his first recording with Jack Teagarden, and his first recording with a half-white, half-African American band. It is also a seamless string of solos, and I make the point in the book that it is looking ahead to where jazz is heading – an integrated band playing the blues together. The piece is forecasting the future, and it is where Armstrong wanted the music to go. It took him a long time to get there, but he eventually got there.

.

Listen to “Knockin’ A Jug”

.

JJM “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.”

RR This is a big song, one that makes Armstrong a crossover artist. That’s the reason Tommy Rockwell wanted Armstrong to come to New York, because it’s a song he knew Armstrong could work his magic on. Armstrong drove the band crazy while spending the entire day trying to get it right, but when that record came out it broke the mold on how to sing these types of pop songs, and how to play trumpet. The way he sings and scats and changes the melody and rephrases it and moans and growls had never been heard before, and nothing would be the same after.

The band complained because they had nothing to do, and if you listen to that record all they’re doing is playing the melody. It is very reed-heavy. It’s fascinating because if you take Armstrong out of the equation it sounds like any 1929 dance band, but when you put him in there the whole thing comes alive. So that melody is droning on for three straight minutes in the background just so you know where it is at all times, so one ear can listen to that melody, and the other ear can listen to what he’s doing on top of it, and it all clicks.

.

Listen to “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”

.

JJM “Ain’t Misbehavin’.”

RR That is the song that made Armstrong a hit on Broadway, and the one he gave credit to for creating his crossover appeal. On the vocal he sounds like he is from another planet – the way he emotes on “Oh baby my love for you” is the birth of soul singing and Ray Charles and James Brown and everything that follows. And listen for the quote from “Rhapsody in Blue.” Five years earlier a lot of the music writers – especially the white music writers – thought that after Gershwin wrote “Rhapsody in Blue” and Paul Whiteman “made a lady out of jazz,” that was where jazz was headed, but now Armstrong moves it ahead. Nobody knew at that time that the real architect of this music was Louis Armstrong. So the fact that he uses Gershwin’s exact melody in the middle of this solo that really turned him into a star is ironic and so perfect.

.

Listen to “Ain’t Misbehavin'”

.

JJM “Blue Yodel Number 9.”

RR This song is the most American record ever made. We created jazz, we created the blues, and we created country music, and for three minutes you’ve got the greatest genius in jazz and Jimmie Rogers – the artist who really puts country music on the map – finding common musical ground on the blues. Even though Armstrong doesn’t sing, it is just all there.

.

Listen to “Blue Yodel No. 9”

.

JJM “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South.”

RR This is Armstrong’s theme song. It’s a problematic song for multiple reasons, mostly because some people think it glorifies the South, and also because it twice uses the word “darkies,” so the fact Armstrong adopted this as his theme song was a sign to many that he was out of touch and out of date. I argue that it is more complex than that. The song was written about New Orleans, which is how Armstrong took it, and every time he sang it he was singing about home. It was also written by three Black songwriters about Black people, which was a point of pride for Armstrong. Regarding the term “darkie,” Armstrong used epithets like that in private conversation all the time, even though it was already verging on the taboo. The early 1930’s were a rough and complex period, and it shows up in lyrics in songs like “Underneath the Harlem Moon” and “That’s Why Darkies Were Born.”

An African American friend of mine makes the point that rap and hip hop artists today use much worse words and make millions, yet Armstrong was crucified for using this word, even though the song was written by African Americans. I also make the point that after he records it he goes on this tour of the Deep South and experiences such over-the-top racism that when he re-records it in December of 1932, he changes the title at one point to “When It’s Slavery Time Down South,” which is the subversive Armstrong in all of his glory. There is no easy way to explain it other than to recognize it as a complex song, and for forty years he opened up every show with it because it put him in the right in that frame of mind of being back home. Also, melodically it has these major 7ths, which is one of his favorite notes, and he just keeps hammering it home. So the song has sentiment, racial pride, warmth and nostalgia, and for all of those reasons it makes sense that he would choose it to be his theme song.

.

Listen to “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South”

.

JJM “Laughin’ Louie”

RR I call “Laughin’ Louie” the quintessential Armstrong record because, as I said earlier, to get the whole package of Louis Armstrong you need that comedy in there. The trumpet playing and singing get you very far, but the comedic elements push it over the top.

Armstrong loved the “Okeh Laughing Record,” which he owned three copies of, and “Laughin’ Louie” was going to be his version of that. Budd Johnson, who played tenor on the song, remembered that Louis got the whole band high before the recording session, and he invited all of their friends to the studio. He opens up with this silly little vaudeville novelty that then goes into a parody of the “Okeh Laughing Record,” but when he picks up the horn and plays in double time like bebop is flowing out of his horn, and then takes a breath and starts playing a cue that he used to play when he accompanied silent movies, it is the most tear inducing, operatic, glorious thing you have ever heard. The entire studio goes quiet. It’s like an emotional roller coaster – those in the studio are laughing and high, but then he douses you with some double timing, just pouring his heart out, and you also hear the strain in his chops because they are starting to desert him during this period. And there it is, if you need a Louis Armstrong experience in three minutes – the highs, lows, the drama, the innovation, the comedy, the opera, the marijuana – it’s all on “Laughin’ Louie.”

.

Listen to “Laughin’ Louie”

.

JJM “Old Man Mose.”

RR That was written by Zilner Randolph and it becomes probably Armstrong’s most popular record with African American audiences. Again, it is one of those records that the jazz critics couldn’t get on board with – they thought it was just a waste of time. There is barely any trumpet on it, it is a call and response vocal – something that George Frazier called “commercial junk”– but in the African American community, “Mose” was this subservient, old African American that was going the way of all flesh. It is an interesting thing, you had Adam Clayton Powell claiming “Old Man Mose is Dead” as a kind of anthem for African Americans in 1935, and when Leonard Feather goes to see Armstrong in Harlem, the Black audience is singing along. It is another one of those records that slipped through the cracks, and when it does get played it is usually used in jazz circles as an illustration of how Armstrong lost his way. But if you lived in an African American community, and if you read the Black press, you can see how important this music was to them.

.

Listen to “Old Man Mose”

,

JJM Many of us who grew up with jazz and figures like Armstrong have deep concerns about the challenges of making jazz music relevant to younger audiences. Armstrong seems to be a central figure in this challenge. How do you imagine keeping the spirit and history of Armstrong alive and relevant to young people in the coming years?

RR When you study Armstrong’s upbringing and music, it answers so many questions you could have about life because you can find something that he lived through and bring it to the current day. He lived through a pandemic, he lived through racism, he lived through the civil rights era. At Queens College I have been lucky enough to teach “The Music of Louis Armstrong,” a graduate level course taken by professional musicians earning their Masters Degree. Of the sixty or so students I have taught, none have admitted to ever really checking Armstrong out. When we start the course and they look at the syllabus they are surprised that they will be spending 16 weeks studying this one guy, listening to his music every week. But I teach them about his history, his music, and the sociology of his time and how he impacted it, and after studying him they turn in their papers and I can see them searching within themselves, understanding that this was such an emotional experience and a needed experience. They ask why they didn’t get this earlier in their studies, or why they hadn’t transcribed an Armstrong solo prior to this class. They also didn’t realize what he had lived through. I’ve even had international students tell me it was the best American history course they’d ever taken.

That’s my way of saying that nearly 50 years after he died we are still coming to the realization of just how big this man’s life was. If you need a 20th century figure to learn from, he’s your man. People could argue Sinatra or Elvis or the Beatles, but Armstrong was born in 1901, dies in 1971, and was there for all the big events during that time. As an African American he had to deal with racial strife and all the barriers he had to break. When media was being created he was a major factor in all of them – records, radio, film, television.

JJM And he left behind quite an archive…

On the set of the Paramount short, A Rhapsody in Black and Blue, the earliest surviving footage of Armstrong on film. Mike McKendrick is in the background on guitar.

RR Yes, and it is there for future generations to see. To your point about keeping jazz relevant, something that I stress with my students about Armstrong is that his talents were so diverse – he could record with the Dukes of Dixieland one day and Duke Ellington or Dave Brubeck the next, and follow it up with recording with a string orchestra or Ella Fitzgerald or Oscar Peterson. He would record pop tunes, show tunes, blues numbers, Hawaiian songs, or anti-bellum songs with the Mills Brothers. He always played like himself and was always 100% himself in everything he did. I think that’s where jazz of today has kind of lost its way. You hear this all the time – “Everybody sounds the same, everybody is playing too many notes and playing the same changes and the same turnarounds” – and jazz musicians today should take a page out of Armstrong’s book by applying jazz principles to today’s pop music like Robert Glasper does with hip hop, or what the Bad Plus was doing when playing music of Nirvana years ago. Like during Armstrong’s time, there are ways of taking what’s going on in the pop world of this day and give it that jazz spin and make it more accessible than just playing 1946 bebop heads all night.

There is a lot to learn from Louis Armstrong, as a musician, as a pioneer, as an innovator, and as a human being. The more you study him, the more you are going to learn. That’s what I am dedicated to – take him seriously, learn about his entire career, listen to his own words, transcribe his music, listen to it all, read his story, and then watch what it does to you as a musician, as a thinker, and as a human. Armstrong is a deep subject, and we are so lucky that he left so much behind.

.

photo William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Louis Armstrong, Carnegie Hall, New York, N.Y., ca. Feb. 1947

.

“’Hello Dolly!’ knocked the Beatles off the top of the pop charts at the height of Beatlemania. ‘What a Wonderful World’ went to number one in England, again displacing the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. In between, he appeared on the pop charts with ‘So Long Dearie’ and ‘Mame.’ A black musician in the 60s, regularly landing on the pop charts alongside some of the most iconic rock and pop acts of all time? That is the very opposite of the times passing Louis Armstrong by. He went along with the times his entire career. His innovations dictated the times.”

-Ricky Riccardi

.

.

_____

.

.

Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong (Oxford)

by Ricky Riccardi

.

.

“Riccardi’s Heart Full of Rhythm is the best account we have of Armstrong’s vital work with big bands – the research is impeccable, the ardor contagious.”

-Gary Giddins, author of Bing Crosby: Swinging On a Star – The War Years, 1940 – 1946

.

“Dedicated research, access to ideal sources, and fine storytelling combine to shed new light and insight on the most interesting and well-documented period of Armstrong’s fabled life. Riccardi has done it again, but even more so.”

-Dan Morgenstern, Director Emeritus of the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University

.

.

Ricky Riccardi is Director of Research Collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum and author of What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years. He runs the online blog, “The Wonderful World of Louis Armstrong,” and has given lectures on Armstrong at venues around the world, including the Institute of Jazz Studies, the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, the Bristol International Jazz and Blues Festival and the Monterey Jazz Festival. He has co-produced numerous Armstrong reissues in recent years, including Satchmo at Symphony Hall 65th Anniversary: The Complete Concert, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong Cheek to Cheek: The Complete Duets, Pops is Tops: The Verve Studio Albums, and two volumes of Decca Singles for Universal Music, in addition to Columbia and RCA Victor Live Recordings of Louis Armstrong and the All Stars for Mosaic Records.

.

.

___

.

.

Editors Note: Ricky Riccardi’s blog “The Wonderful World of Louis Armstrong,” is an absolute treasure and can’t be missed. Of special interest are several Spotify playlists he assembled:

Click here to be taken to a page that features a playlist of music for every chapter in the book. If ever you wanted to hear every major recording of Armstrong’s career, put together by the prominent Armstrong scholar, now is your chance. It is also a great companion while reading the book.

Click here to be taken to a page that features a ten-hour playlist that has almost every side of Armstrong recorded between 1929 – 1934, and each one is preceded by multiple contemporary versions of the same songs by many of the white dance bands and crooners. Armstrong’s genius leaps out of the speakers.

Click here to be taken to a page that features a playlist of Armstrong’s 1935 – 1947 output, preceded by dance band versions of each song. The contrast between these tracks and what Armstrong records is striking, and obvious evidence of his brilliance.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on November 16, 2020, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.