.

.

.

In an interview originally published on Jerry Jazz Musician in 2004, Jack Johnson biographer Geoffrey Ward talks about the first black heavyweight champion in history, the celebrated — and most reviled — African American of his age.

.

.

.

_________

.

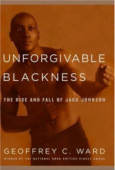

Jack Johnson was the first black heavyweight champion in history, the celebrated — and most reviled — African American of his age. Prizewinning biographer Geoffrey Ward tells Johnson’s story in Unforgivable Blackness, which reveals a far more complex and compelling life than the newspaper headlines he inspired could ever convey.

Johnson battled his way from obscurity to the top of the heavyweight ranks and in 1908 won the greatest prize in American sports — one that had always been the private preserve of white boxers. At a time when whites ran everything in America, he took orders from no one and resolved to live as if color did not exist. While most blacks struggled just to survive, he reveled in his riches and his fame. And at a time when the mere suspicion that a black man had flirted with a white woman could cost him his life, he insisted on sleeping with whomever he pleased. Because he did so the federal government set out to destroy him, and he was forced to endure a year of prison and seven years of exile. To most whites (and to some African Americans as well) he was seen as a perpetual threat — profligate, arrogant, amoral, a dark menace, and a danger to the natural order of things.#

Johnson battled his way from obscurity to the top of the heavyweight ranks and in 1908 won the greatest prize in American sports — one that had always been the private preserve of white boxers. At a time when whites ran everything in America, he took orders from no one and resolved to live as if color did not exist. While most blacks struggled just to survive, he reveled in his riches and his fame. And at a time when the mere suspicion that a black man had flirted with a white woman could cost him his life, he insisted on sleeping with whomever he pleased. Because he did so the federal government set out to destroy him, and he was forced to endure a year of prison and seven years of exile. To most whites (and to some African Americans as well) he was seen as a perpetual threat — profligate, arrogant, amoral, a dark menace, and a danger to the natural order of things.#

Ward’s book serves as the companion to the Ken Burns PBS documentary, Unforgivable Blackness. He joins Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in a conversation about the life of Johnson in a November 15, 2004 interview.

.

.

.

.

________

.

.

.

“At a time when whites ran everything in America, he took orders from no one and resolved to live always as if color did not exist. While most Negroes struggled merely to survive, he reveled in his riches and his fame. And at a time when the mere suspicion that a black man had flirted with a white woman could cost him his life, he insisted on sleeping with whomever he pleased. Most whites (and some Negroes as well) saw him as a perpetual threat — profligate, arrogant, amoral, a dark menace, and a danger to the natural order of things.”

– Geoffrey Ward

.

.

.

________________

.

JJM I was struck by how your book is such a stark reminder of how racist our world was one hundred years ago — on all levels — from the statements and actions of the era’s top political leaders, down to those of the most common man.

GW I have been writing American history of one kind or another for about thirty years, and I thought I had a pretty good intellectual understanding of that fact. After doing the research for this book, I realized that I had no idea how pervasive it was. Racism pervades every story written about Jack Johnson. News stories, ostensibly favorable stories, and critical stories are all written from a racist slant.

JJM And it is only two generations removed from many of us. As much as we would like to believe that all of this is behind us, a mere two generations ago the Mississippi governor James Vardaman said of Johnson, “Personally, I took no other interest in the Johnson-Burns fight than to wish that any white man fighting a Negro for money might get a knockout of sufficient proportion to cause him to continue on to eternal rest.” Sure, this was the governor of Mississippi, but it is still shocking.

GW Yes, you would expect that from the governor of Mississippi, but you wouldn’t expect racist coverage from the New York Times, or the Los Angeles Times, or the San Francisco Chronicle. Their comments weren’t as insane as that, but they were pretty crazy.

JJM I am curious about how you and Ken Burns work together. Did you decide to do the book on Jack Johnson before a decision was made to do a film on his life?

GW No, we started the documentary, and we had originally planned to do a companion volume that was mostly pictorial, the way we had done in the past. But once we got started on this, it occurred to both of us that since Johnson’s life was such a rich tale, a full-scale, scholarly, footnoted biography needed to be written. So, we launched into it.

JJM What resources did you use for the book?

GW There are no real “Johnson Papers” or anything of that kind. It is not like writing about Roosevelt, for example, where you have a library of stuff to go to. I was very lucky because I located in Leavenworth Prison part of an incomplete autobiography he had written, which describes all his big, successful fights in very vivid, personal detail. So I was able to use all of that in the book, which has never been seen before. But most of the resources I used are from thousands and thousands of newspaper accounts. He was very widely covered.

JJM Did you find that his autobiography was at all reliable?

GW Well, it is less unreliable — which I realize is a funny way to put it — than other scholars have thought. I found lots of evidence for some of his tallest tales, and that interested me quite a lot. He was a Texan and a sort of frontier-style storyteller. He embroidered stories about himself, but I don’t think he invented very many of them, which just made the stories better and better as the days went by.

JJM Is there any way of knowing how his early days in Galveston, Texas shaped his view of the world?

GW The great mystery about him is how on earth anyone like him “happened” in the turn of the twentieth century, because it was such a ghastly world for a black person. During his entire life, he never gave in to Jim Crow anything — he simply wouldn’t submit to the system. That of course is the question you want to have answered, which is how on earth somebody got like that? There is no full-scale answer, but he did once say that while he was raised in the Jim Crow South — in Galveston — his neighborhood was very integrated. It was like a lot of neighborhoods in New Orleans. Very poor people of all colors were living together in that neighborhood, and he was never really trained to believe that the white kids he played with were any better than he was. It is not really an explanation, but it may have something to do with how he was. In the end, he is basically inexplicable, the way a Louis Armstrong is inexplicable, or an Abraham Lincoln is inexplicable. You just can’t account for them.

JJM Concerning this you wrote, “Facts about Johnson’s ancestry are hard to come by, and he was himself a cheerful fabulist when it came to retelling his own life. But the first thing he wanted people to understand about him was that because his enslaved forebears had arrived in America long ‘before the United States was dreamed of,’ he was himself a ‘pure-blooded American.’ And because he knew that that was what he was, he saw no reason ever to accept any limitations on himself to which other Americans were not also subject.”

GW Yes, that is what he wanted everyone to believe about him, and with that, he had this American sense that if you have enough courage, and if you have enough superior skill, that ought to be enough to win you success. He acted on that all of his life.

JJM What inspired him to begin boxing?

GW I think he was looking around for something to do. He knew he had extraordinary athletic ability, and he didn’t want to work on the docks in Galveston. He always had the sense that he was set apart and special. He tried various sports — he even tried being a jockey, but he was six feet tall, so that didn’t really play out too well for him. He tried to be a bicycle racer, and he was a good enough ball player to at times play first base with Rube Foster’s teams in the forerunner to the Negro Leagues. But, boxing was available to him and close to home. He began by engaging in informal fights on the beach in Galveston, and then hoboed around the country, where he started to see that he was better than other people at it.

JJM When was his boxing potential recognized?

GW There were two important fights. In one, an aging pro named Joe Choynski knocked Johnson out in Galveston, but because both men were arrested afterwards the fight made headlines and his name became known. The other fight was in 1901 against heavyweight champion Jim Jeffries’ younger brother Jack, who was as tall and strong and a good deal more handsome than his brother, but without the skills. They let Johnson fight him because they thought Johnson would be easy to beat. This was a major mistake. Johnson not only beat him, he beat him in spectacular style. He wore pink tights into the ring, which nobody else had ever seen in boxing — he was a trendsetter from the beginning. When he got in the ring, he handed the promoter an envelope and asked him not to open it. He proceeded to toy with the younger Jeffries for four rounds while he talked to people in the audience. He would lean over and compliment the promoter on the slick tie he was wearing, all the while holding his opponent off at arm’s length. As the fifth round began, he leaned down to tell the promoter to open the envelope. Inside was a note from Johnson predicting he would knock Jeffries out in the fifth round. As soon as Johnson saw that the promoter had read it, he proceeded to knock him out.

JJM Yes, he predicted every blow.

GW That is quite a debut.

JJM Was this brashness — which I guess could be called “trash-talking” today — all that uncommon then?

GW It was called “mouth fighting” in those days, and he was a master of it. Other people may have been good at it, but he was the best.

JJM You wrote, “Being the heavyweight champion of the world was, as the writer Gerald Early has said, something like being the ‘Emperor of Masculinity.'”

GW Yes, it was a symbol of masculine power, and it was thought that the champion was the most powerful man in the world. In a world run by whites, that person almost by definition had to be white man

JJM And they did everything they could to keep blacks from contending

GW They simply refused to let them contend. They could fight each other or they could fight white contenders, but they couldn’t ever fight the champion. It took Johnson five or six years to finally chase down a champion who was willing to give him a shot at it. He did that because he was given an offer he simply couldn’t refuse. He was paid thirty thousand dollars, which no one before had ever come close to being paid.

JJM This is Tommy Burns you are talking about

GW Yes. The fight was held in Australia, and Johnson made quick work of him.

JJM The racist reaction by the Australians to Johnson’s victory was somewhat surprising to me…

GW That kind of white racism was international. The rulers of the British Empire were terribly worried that if Johnson beat Burns, the blacks and Indians and Ceylonese would rise up, and somehow their empire would crumble. The films showing Johnson beating up Tommy Burns and Jim Jeffries were barred from being seen within much of the Empire.

JJM Did Burns fear Johnson as a fighter at all?

GW Yes, I think he knew he was going to lose. Burns actually wasn’t very big, and he had pretty much beaten everybody he could make any money off of. Before the fight, he said he was probably going to get beaten. Of course, that was when he was being realistic. The rest of the time he thought that since he was a white man, he was going to win, that Johnson would become afraid and run away, and that he couldn’t stand being hit in the stomach. There were all kinds of crazy racist theories.

JJM There were many issues within Johnson’s life that may have proved uncomfortable for him. How was his private life reported on prior to the Burns fight?

GW Johnson assumed that he was a great fighter, that he should be honored as a great fighter, and nothing else mattered. His private life was very colorful. He had many women companions, some of whom were white, but that created very little stir until he became champion. When he came back from Australia, he had a white woman with him — whom he introduced as his wife — and that made news all over the country. From then on, he was a target not only of people who didn’t want him to fight, but of people who wanted to tear the title away from him, and who even wanted to kill him.

JJM Why do you suppose he chose to pursue white women?

GW I don’t think he chose to pursue them, I think they probably pursued him. He gave various explanations at various times in his life — that black women didn’t pamper him the way that he wanted, for example — but I don’t think anybody knows why people have preferences of that kind.

JJM You quote him as telling sportswriter John Lardner, “I didn’t court white women because I thought I was too good for the others like they said. It was just that they always treated me better. I never had a colored girl that didn’t two-time me.”

GW Well, I am sure that isn’t true. That explanation is too simple — in fact, all the explanations are too simple. I think he had white women companions so he could flaunt them in front of the white world, but I think that was only part of the reason. He was very fond of those women, and he married three of them.

JJM So here you had a black man who was now the “Emperor of Masculinity,” and who was also marrying white women. Clearly he was a threat to white society

GW Yes, in the crude terms of the times, not only could he beat white men, he could take their women. People were terribly upset about that.

JJM You wrote, “In two decades as a contender and champion, Jack Johnson would never once enter the ring against a white opponent in front of a crowd that was anything but overwhelmingly hostile, and as the years passed and his fame and notoriety grew, the curses and racial taunts he’d been hearing since he faced Jim Scanlon back in Galveston would sometimes be supplemented by threats to murder him.” How did he deal with the pressure?

GW The pressure never seemed to bother him in the ring. As the years went by, and after he won the title, I think the criticism and the hostility and the threats did begin to tell on him. He drank pretty heavily throughout his life, and while it is impossible to know exactly what the cause of that was, it very likely had to do with the pressure he was under. But it never bothered him in the ring, and it never bothered him when he was dealing with the press. He was always Jack Johnson.

JJM How did white Americans respond to Johnson’s victory over Burns?

GW They had to admit that he beat them. It was after they discovered he had white female companions that the real clamor grew to find a white man who could restore the title to what they saw as its rightful owner.

JJM Following the Burns fight, the previous heavyweight champion, Jim Jeffries, claimed that since he retired from the ring as champion, he never really lost the title.

GW Yes, that is what he claimed — that since he retired rather than fight Johnson, and since Johnson had only beaten people Jeffries never fought before, he was still really the champion. It was probably just a ploy to get the lion’s share of the purse. It was a ridiculous argument, of course. If you give something up, you have given it up. As Johnson said, an ex-mayor is no longer mayor.

JJM The writer Jack London reported on the Burns fight for the New York Herald, and concluded his story by saying, “But one thing remains. Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove that smile from Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you.”

GW London was a complicated guy of his period. He was a Socialist, but his sense of brotherhood didn’t extend to black people. In some ways he wasn’t a virulent racist the way some of the other people wrote about it were, but he was a fancy enough writer that the idea of finding somebody to “remove that smile” from Johnson’s face caught on.

JJM Was Jeffries’ interest in returning to the ring motivated primarily by money, or was it because he wanted to restore the crown to whites?

GW The story is that he felt a racial duty to do it. I am sure to some extent that is true, but I think what is much more important is that he made a great deal of money. He also made a lot of money getting ready for the fight — he did a vaudeville tour for more than a year, during which time he went around the country training in public, on stage, and people paid to see it. He made more money doing that than he made in the ring. Then he was offered a lot of money for the fight. So, I think his return was very largely a financial decision.

JJM Their fight was sold primarily as a racial contest

GW Yes, it was called the “Battle of the Century,” and the “Race War.” It was supposed to decide who was going to be in charge: blacks or whites. Johnson was just amused by it. To him it was just a fight. He had fought white guys and he had fought black guys, and he had beaten both, so why should Jeffries be any different? But this fight, for all sorts of reasons having nothing to do with boxing in the ring, became a huge global event.

JJM Jeffries said “I realize full well what depends on me. That portion of the white race that has been looking to me to defend its athletic superiority may feel assured that I am fit to do my very best. I will win as quickly as I can.” Did he really believe that he could beat Johnson?

GW I don’t know for sure, but by the time of the fight he knew he couldn’t. He didn’t really train right. For example, he had mostly old friends train with him, many of whom were the same age he was — and he was older than Johnson. He realized he was far too slow for Johnson. The night before the fight he couldn’t sleep at all, and it probably wasn’t because he was excited. It was because he had this awful sense that Johnson was going to beat him, and how much worse it was going to be after having said all those things about him. Jeffries is not a sympathetic guy, but you can sort of understand how he got put into the position he was in. He too was a victim of ludicrous racism. All racism is ludicrous, of course, but this was especially awful.

JJM An example of this racism is something the former California governor, J.N. Gillette, told a reporter: “Anyone with the least sense knows that whites in this country won’t allow Johnson or any other Negro to win the world’s championship from Jeffries. Johnson knows that.” He went on to say, “He’s no fool. He knows that in order to win that fight, he would have to whip every white man at the ringside, so he has agreed to lay down for the money.” Is there any truth to that?

GW No. He may have been offered money to lie down, as he was in most fights. In this case he certainly didn’t take it. The boxing game was even gamier then than it is now, and there were lots of deals and agreements to carry fights for a certain length of time, which was pretty standard for those days. But he really wanted to win this fight.

JJM The revenues generated by the film of the fights was an interesting aspect of your book. The film rights were such a large part of the fighter’s income stream.

GW It was like pay-per-view is today.

JJM If a fight only went one or two rounds, there probably wouldn’t be much interest in it, therefore this system did encourage boxers to think about making a fight last longer than necessary.

GW That’s right.

JJM These bouts were often scheduled for forty-five rounds. How long were the rounds?

GW Three minutes each. It was a very rough game. In the bare-knuckle days, they used to go seventy or eighty rounds.

JJM You wrote of Johnson, “His style was elegant, refined, distinctive, savored by connoisseurs of the art and science of the sport but not calculated to appeal to those fans who had paid to see a brawl.” That reminds me of Muhammad Ali’s boxing style. What kind of style did these fighters have to utilize in order to go for forty-five rounds? Did they pretty much stand toe to toe?

GW No, they didn’t stand toe to toe, and there was a great deal of wrestling in them. Before bare-knuckle fights were stopped in 1892, a reason fights would go on for so many rounds is because the fighters could wrestle. There was endless throwing of people down, and there were remnants of that in bouts after that. They did very little breaking up of the two fighters, so the guys would stand in the ring and push each other around a lot of the time. Nobody was ever on their toes the way Muhammad was.

JJM Can you describe Johnson’s relationship with the black community following his defeat of Jeffries?

GW That was the height of his romance with the black community. They saw him as a symbol of defiance. It was the only arena in the world, really, in which black people were winning, and he was winning on an international scale. People identified with him enormously. But there were already some middle class, church-going people in particular who worried that his private life — his white wives and flamboyant lifestyle — would tarnish the reputation of their race.

JJM Yes, you wrote that “Johnson proved not only that he could beat a white man, but that he could take their women that they believed were theirs alone as well.” I have to believe that was a concern for everybody.

GW Yes.

JJM Johnson’s interests included the opera, he loved history, and he raced automobiles. Did the complexity of his interests further antagonize whites?

GW All of that was presented by the press in a jokey way, as if people were saying, “You wont believe this. Not only is this guy prominent and has white wives, but he claims to be an inventor.” His claims about being an inventor seemed to be the height of absurdity to writers at the time, but he truly was an inventor. When I wrote the script for the film, I found one patent that he had, and by the time I wrote the manuscript for the book, I had found three. He was an extraordinary man.

JJM One of the inventions he was working on was a flying machine?

GW Well, he claimed he was working on a flying machine, but I can’t prove that. He also claimed that he was trying to find a cure for tuberculosis. But I do know that he had three patents for devices — two of them having to do with cars. One was an improved automobile wrench, and one was an anti-auto-theft device. The third was some kind of a steam winch that lifted very heavy equipment.

JJM Following his defeat of Jeffries, the Feds basically wanted Johnson gone. How did they use the Mann Act for this purpose?

GW They misapplied the Mann Act, which was originally intended to stop commercial traffic in prostitution. They got him because he paid the railroad ticket for a girlfriend to move from Pittsburgh to Chicago. Under some pressure from the Feds, she was willing to testify against him.

JJM Was this testimony agreed to because of some jealousy she felt?

GW It was partly out of jealousy, yes, but it may also have been that the Feds told her she would have trouble if she didn’t testify, and I suspect that is what happened. So, he was basically railroaded into prison.

JJM Yes, and he was left with the choice of going to prison for a period of time or getting the hell out of Dodge.

GW That’s right, which was the option that he chose.

JJM He made his way into Montreal. Who assisted him in getting there?

GW Like all the things in his life, there are five or six explanations. In one, he claimed to have paid local, state, and federal officials in the neighborhood of twenty-five thousand dollars to be allowed to get out of town. Another story is that the great baseball pitcher Rube Foster — who later founded the Negro Leagues — managed to smuggle him aboard a railroad train with the rest of the members of his team, and then fled to Canada.

JJM From there he made his way to Europe.

GW Yes, he made it there and was out of the country for seven years, during which time he lost his title in Cuba to Jess Willard.

JJM How was Willard chosen to fight Johnson?

GW There was a desperate search for another “great white hope,” and when Jeffries failed, they tried all kinds of people. When they realized they couldn’t find anybody skillful enough to beat him, they instead looked for the biggest guys they could find. There were all sorts of giants who were supposed to be able to challenge him, but most of them couldn’t fight at all. They found Willard in Kansas and determined that he could fight some — and he was enormous.

JJM There was also some doubt, which you seem to have put to rest in your book, about whether Johnson lay down for this fight with Willard in Cuba in order to come back to the country without having to go to prison.

GW The reason for the doubt is that Johnson claimed he’d thrown the fight. He said he’d had a deal with the promoters to get him pardoned, and would be allowed to come back into the United States once he had given up his title. There really isn’t any evidence for that at all. If you see the fight you can see that it isn’t true. He won twenty rounds, then he ran out of gas. He was fighting a bigger, younger guy in one-hundred-fifteen degree heat, and he was overweight and out of shape. He simply got caught by a good right hand.

JJM What did he do in the years immediately following his loss to Willard?

GW He toured Europe. During World War I, he was on the periphery of things. He staged exhibitions in small towns, as well as in bull rings in Spain. He tried all sorts of schemes to make money. Among many other things, he was a hustler. He always had four or five new schemes for how to remain famous and make some money.

JJM He claimed to have been an undercover agent

GW Yes, he claimed to have been a spy during World War I, but that is not true. He took a very dim view of the war. He tried to get into the Army, promising that if they let him back into the country and leave him alone, he would serve in the United States forces. Since nobody could guarantee that, he didn’t go into the Army.

JJM He resented Joe Louis’ success, even to the point of attempting to train his white challengers. That couldn’t have helped his standing in the black community at all.

GW No, it did not. He was not popular toward the end of his life. It was twenty-two years before another black man got a shot at the title, and that was Joe Louis. Johnson wanted to be Louis’ trainer, but failed to do get the job. He got more annoyed because Louis’ managers let it be known that they’d told Louis not to act like Johnson. In a way, he became the anti-Jack Johnson; Louis was forbidden to be photographed with white women, he was forbidden to smile in the ring — let alone talk — all of which greatly annoyed Johnson, who saw himself as a pioneer.

JJM Louis felt he had to change his persona because of the actions of Johnson before him

GW Yes, he did. He had to be a sort of denatured version of himself.

JJM I am sure that the issue around his being married to white women was a great contributor to Johnson’s demise. Turn the clock back one hundred years, when black men were lynched for merely looking at white women the “wrong way,” and among this society lived Johnson, exuding self-confidence and flaunting these “taboo” relationships. I have to believe that made his life a lot harder than it may have been otherwise.

GW Absolutely. There is no question about that. But he simply refused to live his life circumscribed by anybody. Black and white people alike asked him all his life, “Just who do you think you are?” His answer was always, “Jack Johnson.” It was the only answer he thought he had to give.

JJM The recent review of your book in the New York Times posed an interesting question of you. I will preface the question with this quote of Johnson’s. “I only hope the colored people in the world would not be like the French. History tells us that when Napoleon was winning all of his victories, the French were with him. But when he lost, the people turned against him. When Jack Johnson meets defeat, I want the colored people to like and love me the same way as when I was the champion.” Did the life Johnson led ultimately leave the black community more inspired than embarrassed and enraged?

GW That is a tough question. The first thing I have to say is that I don’t think anybody knows what the “black community” thinks about anything, because the black community is just as various and complex and richly diverse as any other community.

Johnson was certainly a hero to young men of his generation. He became an embarrassment later. When Joe Louis won the title while “behaving himself,” that pleased that generation. After that, Johnson was largely forgotten. When you think about the fact that he was the best known black man on Earth in his lifetime and that he then became supplanted by other people says something about people’s memories. I think white people are embarrassed by the story, and I think some black people were embarrassed by Jack Johnson. I am hoping that the book does at least a little to restore his memory. He was something.

JJM Well, congratulations on the work. It was a great read, and a wonderful reminder about what an amazing American Johnson was.

GW Yes, that is what I think he is. He was a great American type. He symbolizes Meritocracy, and was a symbol of the American ego. When he wanted something, he went out and got it.

JJM He stood up for so many things. As you said earlier, he looked at himself as an American above all, and he based his relationships not on race but on the quality of them. It is hard enough to do that now, let alone one hundred years ago, when Booker T. Washington was saying this was not the way black men should behave now.

GW Yes, Washington dismissed him as all brawn and no brains. But Washington was envious. Johnson’s fame was far greater than his own. Jack Johnson was an international figure. I don’t think there had been an international black figure before him, and for quite some time there wasn’t one after him.

JJM James Weldon Johnson said of him, “Johnson fought a great fight, and it must be remembered that it was the fight of one lone black man against the world ”

GW Yes, that is it. You can’t say it any better than that.

.

.

____________

..

“I loved him because of his courage. He faced the world unafraid. There wasn’t anybody or anything he feared.”

– Johnson’s last wife, Irene Pineau Johnson

.

_____

.

*

.

“Alas, poor Johnson,” a poem by Walt Mason published in the May 14, 1915 Los Angeles Times following Johnson’s loss to Jess Willard

Alas, poor Johnson, badly whipped,

And of his wreaths and honors stripped;

When he appeared in yonder ring

He was that ring’s unconquered king;

And when he left it, sick and sore,

He was a has been, nothing more,

And all the country felt relief

When Brother Johnsing came to grief;

No words encouraging he heard;

No breasts with sympathy were stirred,

But all were glad to see him slump

Before Jess Willard’s cultured thump,

And e’en the men of his own race

Exulted in his loss of place.

‘Twas not because his skin was brown

That men rejoiced when he came down.

But Johnsing, since he gained his fame,

Seemed destitute of sense of shame,

And laughed with foul, unholy glee,

At all the claims of decency.

An outcast from his native land,

And by most other countries banned,

He’ll skulk, since from the height he’s hurled

Along the edges of the world,

A blot on every decent scene,

A leper with the sign, “Unclean.”

A man all morals can’t defy

And with that sort of thing get by;

And when he falls as fall he must,

Rejoicing follows long disgust.

.

.

Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson

by

Geoffrey C. Ward

.

.

.

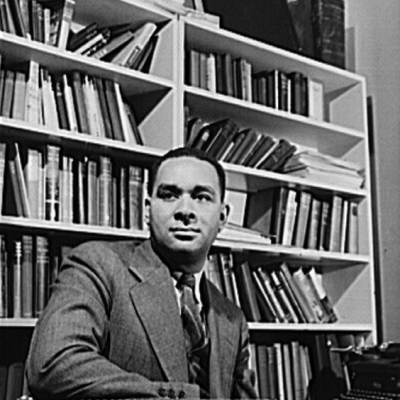

About Geoffrey Ward

.

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

GW Franklin Roosevelt.

JJM Any particular reason?

GW Yes, I had polio when I was a kid, and I grew up in a Democratic household. That combination made him be my hero, and I ended up being his biographer.

.

*

.

Geoffrey C. Ward won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1989. With Ken Burns, he is coauthor of The Civil War and Jazz. He lives in New York City.

.

.

__________

.

.

A selection of photos

(used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.)

.

.

Jack Johnson, 1901, age twenty-three

.

.

In a Galveston, Texas jail with fellow boxer Joe Choynski, 1901. They were incarcerated for taking part in an illegal prizefight

.

.

Johnson with Clara Kerr, 1904, with whom he lived — unmarried — in a white Bakersfield, California neighborhood

.

.

Round fourteen versus champion Tommy Burns, Sydney Australia, December 26, 1908

.

.

Arriving in Vancouver, B.C. as the new heavyweight champion of the world, with Hattie McClay, February 3, 1909

.

.

Johnson watching over a fallen and unconscious Stanley Ketchel, 1909

.

.

Johnson and former champion Jim Jeffries (to Johnson’s left) at New York’s Albany Hotel, 1909, agreeing to title fight

.

.

Johnson with Etta Duryea, Reno, c. 1910

.

.

Johnson, in his corner, prior to the July 4, 1910, Reno, Nevada fight with Jim Jeffries

.

.

Johnson aboard his private train following his defeat of Jeffries, 1910

.

.

Johnson and Etta Duryea, Ballston Spa, New York, 1910

.

.

Johnson with Etta Duryea

.

.

Belle Schreiber, a prostitute Johnson met in 1907, and who claimed to be “Mrs. Jack Johnson.”

She would eventually testify against Johnson, claiming he transported her across state lines.

.

.

November 8, 1912 Chicago American headline announcing Johnson’s incarceration

.

.

Johnson marrying Lucille Cameron, December 3, 1912

.

.

Johnson with Cameron while in exile, Paris, c. 1913

.

.

Jess Willard, the “great white hope” from Kansas who defeated Johnson on April 5, 1915 in Havana, Cuba

.

.

Johnson versus Willard, April 5, 1915

.

.

Johnson on the canvas, appearing to be shielding his eyes from the sun, which fostered the myth that he had thrown the fight

.

.

Poster announcing 1916 Barcelona fight with Arthur Craven

.

.

At a Leavenworth Prison “boxfest,” May 28, 1921

.

.

Johnson with his third wife, Irene Pineau Johnson, 1932

She wrote of Johnson, “As a husband, Mr. Johnson is everything that he could possibly be.”

.

.

.

_____________________

.

.

This interview took place on November 15, 2004, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890 – 1919 author Tim Brooks.

.

.

*

.

.

# Text from publisher.