.

.

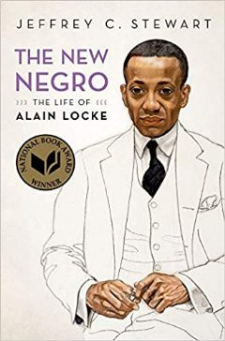

In a 2019 Jerry Jazz Musician interview, Jeffrey Stewart, author of The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke and winner of the 2018 National Book Award for Non-Fiction, talks about Locke, the man now known as the father of the Harlem Renaissance.

.

.

___

.

.

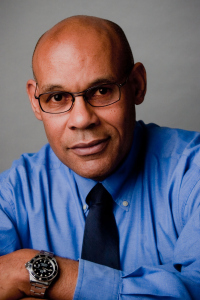

Jeffrey Stewart, winner of the 2018 National Book Award for Non-Fiction, and winner of the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for Biography for his book, The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke

.

.

___

.

.

The Harlem Renaissance, the intellectual and artistic movement of the 1920’s that also helped create the climate for the success of the orchestras of, among others, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Fletcher Henderson, was originally known as “The New Negro Movement,” named after a 1925 anthology of “Negro” literary arts edited by Alain Locke.

Now known as the father of the Harlem Renaissance, Locke’s philosophy was that art and literature could “uplift the race,” and, in the words of Jeffrey Stewart, National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke, “shift the discussion of race from politics and economics to the arts,” and to “establish the idea that Black urban communities could be crucibles of creativity.” In the process, great artists emerged from Locke’s vision and mentorship – artists like, for example, the poets Langston Hughes, Claude McKay and Countee Cullen, and the writers Zora Neale Hurston and Jean Toomer.

Locke was a complex, brilliant man. Harvard educated and the first African American recipient of a Rhodes Scholarship, Locke faced obstacles not only due to his race, but also because of his lifelong search for love as a gay man. Despite (and in some cases because of) these challenges, Stewart writes that Locke succeeded at promoting “the flowering of Black culture in Jazz Age America and the literary and artistic work of African Americans as the quintessential creations of American modernism.”

Stewart’s The New Negro is a great achievement, a book renowned biographer Arnold Rampersad, author of books on Langston Hughes and Ralph Ellison, called “one of the finest literary biographies to appear in recent years.” Stewart joins Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita in a March 25, 2019 interview about his book and Locke, the guiding spirit of the Harlem Renaissance.

.

.

________

.

.

Editors note: “The New Negro” is a historically accurate term that was used in the title of the March, 1925 edition of Survey Graphic, edited by Alain Locke.

Wikipedia defines “The New Negro” as a “term popularized during the Harlem Renaissance implying a more outspoken advocacy of dignity and a refusal to submit quietly to the practices and laws of Jim Crow racial segregation. The term ‘New Negro’ was made popular by Alain LeRoy Locke.”

It is within this context that the term is used throughout this discussion.

.

.

_____

.

.

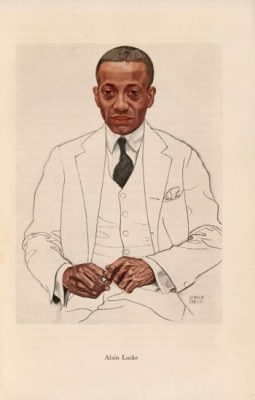

Alain Locke, in an undated photograph

.

*

.

“’Beauty. Its variety is infinite, its possibility is endless,’” as W.E.B. DuBois wrote in 1926. He went on to note, however, that beauty is denied the ‘mass of human beings; who are ‘choked away from it, and their lives distorted and made ugly.’ The charge to humanity was a challenge to all of us. ‘Who shall right this well-nigh universal failing? Who shall let this world be beautiful? Who shall restore to men the glory of sunsets and the peace of quiet sleep?’

“Alain Locke provided one powerful answer to these questions, by asserting something quite radical in the 1920s, something radical today – that Black people are charged with righting this universal failing, by demanding the right to beauty in their own lives, lives distorted in the public discourse of race relations, and demeaned for not measuring up to standards mistakenly described as White. What Locke demanded is the right of African Americans to beauty, to speak of and write about, and carve out realms of beauty unnoticed by most of America because that America itself was lacking in, denied the benefit of, seeing its life as beautiful, ground down daily by a labor unrewarding as much as it is blinded to beauty around us. America was supposed to be the promised land, the place where this ‘universal failing’ of fallen man was righted, where the ‘glory of sunsets’ was to be restored, but instead had become, by 1925, and even more by 2017, a place of unquiet sleep.”

-Jeffrey Stewart

.

___

.

.

JJM .Congratulations on your great achievement, Jeffrey. It is a privilege to speak with you, and thank you for taking the time to share your work with me and our interested readers.

JS. Thank you for having me.

JJM .When did you start writing your book?

JS. It wasn’t until the 1990’s – from about 1994 – before I started seriously writing it, although I had been doing research on Alain Locke off and on for many years before that. I was made aware of Locke when I was in graduate school at Yale in the 1970’s. Then, in the 1980’s I began to pick it up a little bit, and then put it down. In the 1970’s I went to Washington D.C. and was able to nose around and interview some people, which I was very fortunate to do since many of them passed away later, and these early interviews allowed me to have their voices and their views of Locke be part of the book. If I had started more recently I never would have had access to these people. So, I have been working on and off on the book for about thirty years.

JJM .Much of the primary source material that you used are letters between he and his mother…

JS. Right, and also his files at Howard University in Washington, D.C. I taught at George Mason University in Washington for a while, which allowed me to be near the files, but when I came out to the University of California Santa Barbara in 2008 and got away from the files a little bit, that really helped.

JJM .You cover so much rich history of Locke’s life, which is the life of a brilliant man living in complex times. Harvard educated, Locke was the first black man to be chosen as a Rhodes Scholar, who, in addition to the challenges he faced as an African American during his era, also faced challenges as a gay man. Given that Locke is most known for his leading role in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920’s, I would like to focus much of our time on his work within that topic. Before getting that, I do have some background questions…

JS. Sure.

JJM .His father died when Locke was a boy, and his relationship with his mother Mary was intimate throughout his life. How important was her support of him to Locke?

Mary Hawkins Locke, c. 1921

JS. Locke was an extremely precocious and gifted child, and his mother basically devoted her life to him. This is not completely surprising, since mothers in the late 19th and into the early 20th century often devoted themselves to their gifted sons. But, he also returned the favor in the sense that he took her everywhere he went. For example, when he was at Oxford, and later as a Rhodes Scholar, he insisted that she come over and tour Europe with him, which was pretty unique. His mother was like his partner up until the time she died in 1922, and when she did die, that opened up an incredible gulf of longing and alienation and loveless-ness, essentially, that dominated much of the rest of his life.

JJM .On one of his trips to Europe with her, he even referred to it as a “honeymoon”…

JS. Yes, it really was very much like a husband-wife relationship. She was a school teacher in Camden, New Jersey, and she basically used all of her funds to make it possible for him to go to college. Very early on in their letters, when he went to Harvard in 1904, you could see that he was essentially managing their mutual finances, and was pretty much functioning as her husband.

JJM .She was skeptical about him being accepted as a Rhodes Scholar…

JS. Early on, he had an incredible drive for accomplishment. He read a lot and knew that Cecil Rhodes had made millions out of money taken out of Africa, so Locke said he felt it was appropriate that he be one of the recipients of the scholarship. His mother didn’t think they would give it to him, but they did. There were various rumors that the scholarship committee didn’t know he was black, but of course they knew because they interviewed him. But, partly due to the committee’s liberalism, and also partly because the Rhodes Trust didn’t exclude people on the basis of race, they felt they should not exclude him. He had some of the highest scores of any of the applicants, but he wasn’t a traditional sort of Rhodes Scholar, who is usually this sort of burly American who has distinguished themselves in sports. While he did serve for a while as a coxswain on rowing teams, he was very small, only 4’11” tall and weighed about 98 pounds. Locke actually didn’t encounter any race issues until after he got to Oxford.

JJM . An interesting part of Locke’s biography is that his thesis at Oxford, “The Concept of Value,” was rejected, yet he lied about that when he returned to the United States, stating publicly that he had actually received his Oxford degree.

JS. When he was at Oxford, he had two problems. One was that he didn’t have the money that other people who went there had. The Rhodes Fellowship was good, but people lived very well there – particularly the Oxford undergraduates – and while trying to live up to their expectations, he fell into debt pretty quickly. The other thing is that the southern Rhodes scholars who were there were incredibly angry that a black person had received this coveted award. You don’t really sense it now, but in the early part of the 20th century, receiving a Rhodes scholarship was an incredible honor for the Anglo American, and then to have this black guy over there diminished it in their sense, so they did everything possible to exclude him. To counter this alienation from the American scholars, one of the things he did consistently was to socialize with the English, which got him into financial trouble.

Hertford College, University of Oxford

In addition, very few Rhodes scholars are prepared for the level of rigor required in Literae Humaniores, which is a coveted degree program there. He couldn’t manage the amount of Greek and Latin that was necessary, so he switched to philosophy at a time when philosophy was under transition – value theory, pragmatism, and pluralism were the rage in America and in Germany, but not in very conservative Britain. This led to him leaving Oxford for Berlin, where he took up residence and wrote his 400 page thesis “The Concept of Value,” which is quite a revolutionary work. However, at this time he had lots of debt (owed to Oxford), and of course him being black while also writing on a subject that Oxford didn’t really like, so his thesis was denied. This rejection is really quite remarkable because most thesis are not 400 page, original philosophical works, so there is some sense that there was a bit of bias toward him, perhaps caused by his behavior but also by his subject matter.

Locke did feel under pressure. It is hard to capture now, but a black person receiving this honor was so unusual – it was in all the newspapers before he left, and all sorts of black people celebrated him as a symbol of intellectual accomplishment at a time when, of course, black people were not considered intellectual leaders in America. So he felt this burden, and to come back a failure gnawed at him. I found a note that he wrote to himself in the 1930’s – which was thirty years later – where he tried to rationalize his decision to lie about receiving his degree. He thought that if he were honest, then he would have to explain that he felt race was a factor in their decision, and he never wanted to accuse people of racism, which would have been another controversy, from his standpoint. But I also think that he couldn’t face the fact that until that point in his life he had been an unmitigated success, and that he had to deal with the problem of failure.

JJM . On top of that, he had pressure from his mom, who wrote to him, “You cannot afford to fail as the first and only one of your race – and more than all – for my sake – because I have my heart and soul fixed on it.”

JS. Yeah, that is quite a statement coming from your mother. Thanks, Mom!

JJM . How did this failure inspire him?

JS. When he went away to Oxford he had this fantasy that James Baldwin and other black intellectuals had when they went abroad, and that is they think they will be able to escape, once and for all, race. But race did find him over there, and once he realized that he wasn’t going to become a diplomat, a cosmopolitan man of the world, he had to return home as a “race man,” as someone who championed the race.

Locke also had a very interesting relationship at Oxford with Horace Kallen, a Jewish graduate student in philosophy he had met at Harvard and who was trying to work out a basis for a kind of Jewish-American identity. They talked about the issues of exclusion and prejudice, and together they came up with this concept of cultural pluralism, which was essentially the idea that America didn’t have to be a single culture, that it was a plurality of cultures, and that cultural diversity could actually be a benefit for America, not a detriment as is so often narrated today. So, when he came back to America, that became his calling card, that he was going to celebrate black culture as being something distinctive and something that was a contribution to America, not something that was a “taking away” from America. This became his platform through much of the 1910’s. He then returned to Harvard, where he had distinguished himself as an undergraduate, and earned his PhD in Philosophy in 1918. That is somewhat covered up beneath the Oxford experience because in the United States, an Oxford degree was almost of no consequence, but a PhD in Philosophy – and being the first black person to earn one – was a distinction that he always had.

JJM .What was Locke’s vision of himself at that time?

JS. The thing that is interesting about this that I confronted toward the end of writing the book was that his signature concept is of the “New Negro,” which is someone who has the agency to create themselves anew, and in new circumstances. He drew this from the great migration of black people leaving the south in the 19-teens, during World War I, and coming north. He said this wasn’t just a geographical movement, it was also a psychological transformation from a kind of medieval 19th century agrarian identity to a modern urban one. An example could be how you look at the development of jazz out of the blues – the creation of a new subjectivity through change.

I came to feel that he also felt that way about himself. He constantly refashioned himself in new circumstances and felt there was no real need for consistency. For example, he had been a staunch universalist, an almost anti-black character at Harvard and then going over to Oxford, but he came back and was a race man, even something of a proto-black nationalist. He felt that part of being human was the ability to reinvent oneself, so he chronicled that concept – one’s capacity for reinvention – in the New Negro.

“Locke’s psychosocial skill as a harmonizer of divergent interests, perhaps gained as a young child from a household of strong-minded, disagreeing parents, became a way to create collaboration across difference that moved the ball forward in adult education and progressive community education. That skill allowed Locke to go outside academia and find support for elite, trained, Black radical scholarship to reach a wider public, a still unrealized aspect of Black Studies today.”

-Jeffrey Stewart

JJM .You wrote that he looked at himself as a “harmonizer between black and white civilization.” These experiences that he had overseas in the white world gave him a unique perspective and ability to bridge the racial gap…

JS. Yes, I think that “harmonizer of divergent values” comes out of his “The Concept of Value” thesis – the idea that values are contextually formed, that our values actually change when they move from one context to another, so that elements of values that Africans brought into the United States would persist and be transformed in the American context, leading to something like “African American.” Then, “American” is itself almost an idea, something that is always in motion, under construction that black people were a part of as well. Locke felt that the Europhilic notion of American culture that was so dominant in the 1920’s was essentially a myth, or a mask, for a much more dynamic interplay of cultures going on, and that people who came to the fore and who could navigate between those, whether they were white or black, felt comfortable in different value systems, and in different contexts. Those would be the new Americans – like the “New Negro” – who could fashion a future.

JJM .What did he believe the function of the black artist to be at that time?

JS. He initially felt that black artists in the early part of the 20th century were often so obsessed with fitting into what Cornell West has called the “white normative gaze” about beauty, art, and what’s appropriate that they often struggled to find their own vision in their art, and that artists should look at African art as inspiration. This was a time, from approximately 1907 to 1930, that African art was being discovered by modernists, which led to a revolution in European art – cubism, abstraction, and conceptualism. Locke saw that and felt that if we could do that from the African side, it is possible it can also be done from the American side, so he encouraged black artists to be self-identified, and to create art influenced by black culture.

I interviewed Lois Mailou Jones, who was a wonderful artist and educator at Howard University and who used to run into Locke there. She was French post-impressionist in the way that she approached art, and she said that one day Locke asked her why doesn’t she do something on “your own people?” She said this was a challenge to her that led her to go into a whole new direction, which she found to be quite fruitful, and led her to be very popular during the black arts movement of the 1960’s. So, in a way, Locke anticipated the black arts movement that emerged in the 1960’s and 1970’s, which is now being chronicled in an exhibition called “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power.” The entire perspective that comes through in that exhibition is really a “Locke-ian” concept, that the image of black people should be replicated by and transformed by black artists and their art.

JJM .You write about how Locke was inspired by the Germans and the Irish and the Italians, as well as by the poet W.B. Yeats, who argued that people needed “‘imaginative’ literature, not sociological or political treatises, to invite them to dream a new future for themselves based on their glorious past.” This was in opposition to the philosophy of W.E.B. Dubois, whose view of art was more political…

JS. Yes, DuBois had a more weaponized view of art. Both of them recognized that in the dominant medium, the images of black people in the 1920’s were always caricatured and demonized. So Dubois’ notion was for artists to counter these degrading images with more realist, sympathetic, and empathetic images, and he did that by publishing pictures and art of black women, largely, on the covers of Crisis magazine. Locke accepted that but thought that we can go beyond that, we can actually imagine a future image or identify for ourselves that is not always in reaction to what the other side said, that if we are always reacting, then we are limiting our possibility.

He got his interest in Yeats from his close friend Charles Dickerman, who was studying the Irish Renaissance when they were at Harvard. Yeats always wanted the Irish libraries to be stocked with poetry and literature that was based on Irish folklore and culture that he felt would, in turn, stimulate Irish modernism and imagination. I think Locke got the idea that he could do that in the black community, where literature and art can lift its imagination and their attention away from the megaphone of racism to something deeper and more permanent.

JJM .Locke was the guest editor of Survey Graphic, where “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro” was published. Graphic’s editor, Paul Kellogg, was white. What kind of complexity did that create?

JS. One of the chapters in the book is called “The Dinner and the Dean,” which talks about this great 1924 dinner that Opportunity magazine editor Charles Johnson had at the Civic Club, when there was an “introduction” of the black artists of that time – people like Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston. Kellogg came to that event and, being fairly astute at tying expressive forms to sociological forms, was inspired to do a special issue for Survey Graphic, which was a sociological journal. He asked Locke to work on this, and he immediately shifted away from the sociological, putting all the poetry and literature in the front of the magazine, and put the articles about crime and Harlem in the back. This edition was called “The New Negro.”

Regarding how they worked together, even though there was some tension between them, I think that they actually worked very well together. As an editor, Kellogg respected Locke’s intellectual authority and allowed him to take the lead and make these configurations. Kellogg also brought things to the relationship that Locke wasn’t able to. For example, he introduced Locke to Winold Reiss, a German artist who had illustrated some of the earlier editions of Survey Graphic, and who had produced a wonderful set of portraits of black intellectuals and everyday people in Harlem that Locke then used for “The New Negro.” So, Locke felt that “The New Negro” could not succeed if it was based solely in black expressive culture, that white people and American culture broadly needed to be engaged. This somewhat distinguished the Harlem Renaissance from the Black Arts Movement of the 1960’s, which was much more aggressive at keeping white participation at bay.

JJM .And the work of Reiss changed the way African Americans were depicted at that time…

JS. Yes. Not everyone was a fan of the work, but he influenced the artists Lois Mailou Jones, Richmond Barthe, and even today you can see traces of his approach in the work of a famous artist like Kehinde Wiley, who poses the black subject against a background that heightens not only the color, but also the cubic and three-dimensionality of the image.

Reiss was also particularly good at creating startling works that reproduced really well, and they looked great in the magazine. This edition became a sensation – Survey Graphic: “Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro,” sold out two complete printings, and even today you can buy a facsimile of it, produced by Black Classic Press. I have carried it around with me and people always react to it because it is just a startlingly beautiful representation of black aesthetics.

JJM .This magazine then became the basis for Locke’s more comprehensive collection, The New Negro…

JS. Yes.

JJM .The Survey Graphic wasn’t without controversy within the black artist community. There were a couple of instances where Locke edited the work of poets, for example…

JS. Yes. Locke was always a person who felt very confident about his vision of things, and he exerted a kind of power that critics and editors used in the early 20th century that is less evident today. If he determined what was right, he was going to do that. Also, many of the artists he represented were abroad, and communication wasn’t what it is today, so they would find out later on that Locke had used their poem, or changed a word or two, and they would be mad about that. On the other hand, they wouldn’t have been published in those venues if it hadn’t been for Locke.

JJM .Locke’s view of jazz music is quite interesting. You wrote in the book, “Locke responded to jazz more as a black Victorian than a modernist, who saw jazz as a loud and wild music culture that lacked, from Locke’s perspective, the kind of rigor and reflection crucial to art of value.”

JS. In the course of working on the Survey Graphic, Locke collected essays from various people, some of whom weren’t particularly good writers, or at least not at the level he wanted them to be. So, at times he rewrote their essays, and one of those he rewrote was J.A. Rogers’ essay on jazz, “Jazz at Home.” Following its publication, Rogers wrote Locke a letter in which he says, “I am much indebted to you for your editorship of it. Nevertheless I am inclined to say in all good nature that there was injected into it a tinge of morality and uplift alien to my innermost convictions.” So here is one of these contradictions; Locke is gay and sexually active, yet at the same time he is very Victorian, which leads him to be moralizing toward those forms of black culture he didn’t like, such as jazz, which to him came out of the houses of prostitution of New Orleans. Also, he was a classical pianist who really loved classical music, and many of those people, as we know, were reading Theodor Adorno and others who didn’t like jazz. So all these things make his vision a bit dated when it comes to jazz. For me, I had to work past that because I love jazz, therefore I just had to accept that he was wrong on some things.

JJM .He did admire Duke Ellington…

JS. Yes, he did like Ellington, and when he came to write about jazz in the 30’s, he basically said that Gershwin had done more with the black forms in jazz than anyone else except Duke Ellington. So he wanted a certain kind of formal exploitation of the work that he found in Ellington. Of course, Ellington was also a very sophisticated, accomplished, handsome man…

JJM .The very definition of a “Black Victorian,” which is what Locke grew up around…

JS. Yes, coming out of Washington D.C., but translating that into a sophistication that was very modern. There was a certain “dandy” quality to Duke Ellington that he made almost universal and institutionalized in black culture, so that when you think of Miles Davis, for example, and other people even in the 50’s and 60’s – how they dressed, and how they carried themselves – much of that level of sophistication came from Ellington.

JJM .You wrote, “In the 1920’s art was used to bring harmony between the races and providing an opportunity for gradual reform of American attitudes. By the 1930’s, literature carried as a subtext a confrontational approach to social change in America – something Locke could not stand.” How did Locke come to terms with this change?

JS. It was difficult for him. He had this institution presented to him by Opportunity magazine called the “Retrospective Views,” which was quite a unique thing. Every year he would survey what were the most significant books of African American subjects, and comment on them, and if you read those writings from approximately 1929 to 1940, you can see him wrestling with this. He had this notion of art as forming and performing this “harmonizer of values” role between black and white, but in the 30’s, with the emergence of Marxism and what was called “proletarian literature,” the idea that conflict was good became hegemonic. He felt that we should at least try to resolve conflicts between whites and blacks, and take down the society that has perpetuated these conflicts. So this was difficult for him to come to terms with. However, as the 30’s went on – and in particular after the riot in Harlem in 1935, when Kellogg asked him to write an essay about it in which he somewhat poo-pooed the idea that poverty and desolation were the source of the riot, which he was criticized for – he realized that he couldn’t continue to be the voice of the black intelligentsia the way in which he had been unless he embodied this conflict and embraced it. So he began to move much more toward the left and to associate himself with what he called “The Newest Negro,” rather than “The New Negro” of the 20’s.

JJM . He saw art in the ashes of that riot…

JS. I think that the art changed, where it went from someone like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, who largely built their literature on the working class but almost in an isolation from larger social and economic forces, to somebody like Richard Wright, who was basically saying that humanity is being destroyed by poverty and segregation in the United States. I will say that Locke was one of the first to defend Richard Wright against those more mainstream critics who felt that Native Son was too violent, and was too much of a caricature of black anger. He was one of the first, basically, to take up and defend him as being the logical evolution. The “New Negro” was never a static phenomenon for him, it was always something that was being refashioned by social circumstances, and by the artists themselves, so he felt it was great that Richard Wright came up with Native Son because somebody was trying, however successfully, to capture the mentality of those who had been created by American racism and American capitalism.

JJM .He saw that Native Son was a tool of change…

JS. Yes, I think that is true. At times he wanted it to be a more accurate portrait, and he felt like all of the attention in Native Son was due to its appeal as “art as a weapon.” He understood the need for that, but he was constantly coming back to the question of after we use art as a weapon, is that all that we want from art, or do we want some type of spiritual transformation, which he felt had to accompany political transformation in order to be permanent and sustainable.

JJM .One of the chapters in the book is titled “Transformation,” in which you write about him refashioning himself as a hyper-masculine and an aggressive male persona during the late 30’s…

JS. Yes, he tried to fit in with the new identity of black maleness in the 30’s, the working class hero, which of course Locke never was. He would go to these working class, communist-inspired meetings, so he had to masquerade a little bit in those circumstances, but he felt that was perhaps a dimension to his personality that had been suppressed. The downside is that he tended to be very harsh and hyper-critical toward women writers and women artists. While he would provide a tremendous amount of support to women like Zora Neale Hurston, or Lois Mailou Jones, in general that hyper-masculinity mask, unfortunately, meant that he helped far more male artists than female artists during his career.

JJM . What is Locke’s most profound gift to us?

JS. I think this idea that we have agency, even under the most trying of circumstances, to reinvent and refashion ourselves into something new, something that is in conversation with our times and our contexts, and that there is a “New Negro” in all of us. He often said if black people can reinvent themselves, why can’t all Americans? If black people can create such enduring forms of art, music and literature in spite of their trying circumstances, we all have that capacity in us. In that sense it really comes out of pragmatism and William James and the idea that you can actually become what you want to become if you are relentless in pursuing that goal. Locke was a relentless person, and I take away from his life this persistence, this refusal to give up in spite of homophobia, racism, and even “size-ism” – sometimes he said he was doomed because he was so short and tiny and all of the other famous black men were big and tall. He also had a heart problem , so to a certain extent he was disabled, yet he refused to let that stop him

Finally, I believe Locke had internal conversations to thwart the normal way in which people use excuses for themselves. One great exception to that was the Oxford situation, where he, to a certain extent, fell back on race as an explanation for his failure. Other than that, he generally accepted his setbacks, but picked himself up very quickly and got back in the game, and that is probably what we all need to be able to do.

.

___

.

‘Portrait sketch: Alain Locke’, The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925), by Winold Reiss

*

“A people, an often used but seldom understood concept is…an unwavering sense of destiny among a group of humans who, for whatever reason, started out together in a place, developed a history, and used that history to create a future out of its present. Black people had that history, that shared set of experiences, and managed challenges wherever they went – and demanded to be taken on face value, to be appreciated, seen as beautiful despite the ugliness of lives in America, and did so regardless of what anyone else thought.

“Locke demanded that artists be able to carve a beauty out of that mean experience without having to reference continually the struggle in the streets for citizenship rights seemingly always denied them. He wished for art that transcended the need, however valuable, to generate propaganda to fight the good fight for America. Black people, in other words, were more than simply civil rights – they were a people with a right to all of humanity, and Locke saw himself as the one to right that ‘universal failing.’”

-Jeffrey Stewart

.

.

___

.

.

.

The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke

by

Jeffrey Stewart

.

.

This telephone interview took place on March 25, 2019, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita. With gratitude to the author for making himself available, and to Oxford University Press.

.

.

___

.

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may also wish to read our recent Roundtable conversation, “Religion ‘around’ Langston Hughes, Billie Holiday and Ralph Ellison” featuring professors and authors Wallace Best, Tracy Fessenden, and H. Cooper Harriss.

.

.

.