.

.

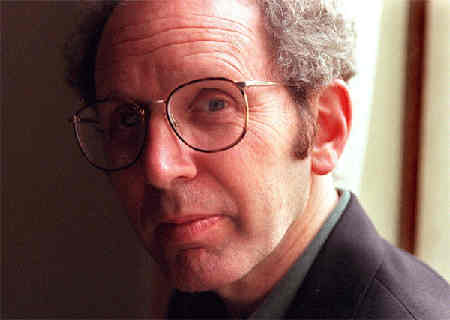

Peter Guralnick, author of Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke

.

He was the biggest star in gospel music before he ever crossed over into pop. His first single under his own name, “You Send Me,” was an historic success, going to number one on the charts and selling two million copies. He wrote his own songs, hired his own musicians, and started his own record label and music publishing company. At a time when record companies treated black artists like hired help, he demanded respect and a recording contract equal to that of top white artists of the day.

And Sam Cooke connected, in songs like “Wonderful World,” “Chain Gang,” “Another Saturday Night,” and “Having a Party” – seemingly effortless compositions that still sound fresh today. In a biography that for the first time tells the full story of Sam Cooke’s short, blazing life, prizewinning author Peter Guralnick captures a personality so vivid, so appealing, that it is almost impossible not to fall under its spell. At the same time, Dream Boogie re-creates in remarkable detail the astonishing richness of the African American world from which Sam Cooke emerged, and the combination of style, wit, and resiliency that was necessary in order to survive and overcome the pervasive prejudice of the day.

And Sam Cooke connected, in songs like “Wonderful World,” “Chain Gang,” “Another Saturday Night,” and “Having a Party” – seemingly effortless compositions that still sound fresh today. In a biography that for the first time tells the full story of Sam Cooke’s short, blazing life, prizewinning author Peter Guralnick captures a personality so vivid, so appealing, that it is almost impossible not to fall under its spell. At the same time, Dream Boogie re-creates in remarkable detail the astonishing richness of the African American world from which Sam Cooke emerged, and the combination of style, wit, and resiliency that was necessary in order to survive and overcome the pervasive prejudice of the day.

Dream Boogie tells a story at once tragic and true: Sam Cooke’s rapid rise to stardom; his troubled marriage and relationships with women; his triumphant recordings and – along with Ray Charles – his reinvention of rhythm and blues as soul music; the joy he brought to live performance and the rolling parties of the road tours; and the senseless waste of his death by shooting at the age of thirty-three.#

In a December, 2005 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita, Peter Guralnick talks about his book and Sam Cooke’s epic American life.

Photos and excerpts used with permission of author

.

___

.

“And my baby leave home

‘Cause things ain’t right

Oh, but I get to feeling – ha ha – so all alone

And I dial my baby on the telephone

And I tell her, “Listen here, operator,

I want my b-a-a – aby,

Onnnn, operator, I want my baby.”

Finally the operator get my baby on the telephone

And I tell her, “I got something to tell you, honey.”

The minute I hear my baby say hello

S-s-s-s-something start to move deep down inside of me

And I tell her, “Listen to me, baby,

I know I didn’t treat you right sometimes

And I want you to know one thing”

.

He has them now. There’s no doubt about it. With all the tried-and-true methods of his gospel training, he has drawn out the tension until it is almost unbearable, people are screaming, they are crying out for release, the level of emotion almost visibly rises, the audience becomes his congregation.

.

“I just want you to know one thing

And that’s

Darling,

You-u-u-u-uuuu, ohhhhhhh you SEND ME

Oh-ohhhhhh, you send me

Ha Ha, that’s what I want to tell you, baby,

O, oh-oh-you-ou, awww, you send me

Aw, let me tell you one more time

Oh, yo-u-u-u-u-u

Oh, baby you send me

Oh-whoa-oh-ohohhhhhwowohhhh – Ha ha –

Ohhhwhooawhoaoh

Honest you do”

.

– Sam Cooke

courtesy Joe McEwen

.

.

___

.

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Sam Cooke, 1965

.

“I write songs that start slowly and then work in little by little to this pounding beat. That is where the excitement is. But I still have my religious beliefs. Our forebears thought you couldn’t sing [both] pops and spirituals, but I have rationalized this. I can do anything I want and still have my religious beliefs. My philosophy of life is: Do whatever is best for Sam Cooke.”

– Sam Cooke

.

___

.

.

JJM Your book is an amazing combination of entertainment and scholarship, and a great vehicle on which to revisit the culture that Sam Cooke was such an integral part of. You wrote, “The Sam Cooke that I discovered was a constant surprise.” What sort of surprises did you encounter during this process?

PG It was the kind of surprise that you encounter when you essentially remove all preconceptions, whether your own or those that are imposed on you. It is the kind of surprise that you would find when looking with fresh eyes at any of the people to whom you are drawn in real life and discover the various and sometimes contradictory layers that exist in all of us. These are the layers that are essentially set aside when we reduce our perspectives to either judgment or anecdote. The kinds of things that I discovered about Sam don’t necessarily reveal themselves in an interview format, but, as an example, one of the things I discovered was his deep interest in reading. While I knew he read, my research for the book led me to an understanding of the depth of his interest — the kinds of things he read and what he presumably took out of them — and to set this in the context of someone who is in the process of constantly evolving.

JJM The depth of his reading was amazing. He was really into African American history, and James Baldwin seemed to be a favorite of his.

PG I recently saw John Hope Franklin a couple of times during my book tour. On one occasion he spoke after Bill Clinton and before me in the House chamber in Austin, Texas. By the time it was my turn to speak, the chamber had emptied out substantially! When I spoke, I talked about how people frequently ask me what Sam Cooke would be doing if he were alive today, and how I believe he would unquestionably be doing something great — he might be mayor of Chicago, for example, or he might be the head of a major record company — but if I were asked what he would be doing on this particular day, I was sure he would have been there listening to President Clinton and John Hope Franklin, being reinvigorated, re-inspired, and recommitted to the movement and the idea that there really can be progress, even in the face of some of the disheartening developments of recent years. Later, I told John Hope Franklin that his 1947 book, From Slavery to Freedom, is what first triggered Sam’s interest in black history.

Getting back to your question concerning what surprised me about Sam — this was not necessarily a good discovery, but it was certainly surprising to learn that, despite the sense you get of him that he was always controlled, smooth and sophisticated, his temper could flare up in certain situations, whether it was at the Palm Café with Jess Rand, when a guy came up to him and challenged him to prove that he was indeed Sam Cooke by singing him a song, or at the Holiday Inn in Shreveport, which he was turned away from because he was black. Those kinds of things were surprising — not on any grand scale, but they were surprising. And while I would like to think that the book might approach a grand scale, it can only do so if the specifics hold up.

JJM How did Sam stand out among the other young church singers?

PG From the testimony of people who knew him as a sixteen or seventeen year old, or as a young quartet singer with the Highway QCs, it is clear that he stood out as a remarkable person in a remarkable world. As a singer, he stood out in a number of ways. When J.W. Alexander was manager of the Pilgrim Travelers — as successful a gospel quartet as there was at that time — he picked Sam out from among the Highway QCs not just on the basis of his talent but on the basis of his personality, as someone who, as J.W. said, was just so damn likable. This was despite the fact that he was not yet fully in control of his voice, nor had he achieved the technique for which he would later become known. But he communicated something to everyone in that audience. Another outstanding aspect was his ability to improvise on a theme — essentially to rearrange Bible verses in an original way, improvise on the melody, and always come back in exactly the right place, which was something he could do even when he was with the QCs.

JJM What did it mean to be a member of the Soul Stirrers at that moment in time?

PG When Sam joined the Soul Stirrers, it was a big step up. As wide a path as the QCs cut — not just in Chicago and the Midwest but in Memphis too, and without a recording contract — there was nowhere else for them to go. The Soul Stirrers, on the other hand, were one of the major gospel quartets, and one of the few who recorded for a major independent company. R.H. Harris, the Soul Stirrers lead singer, was a primary influence on a wide array of vocalists, from a screamer like Archie Brownlee to a crooner like Sam Cooke, who replaced Harris in the Soul Stirrers. Joining the Soul Stirrers meant you were now part of an extremely well established group that was part of major programs. To use a baseball metaphor, it was like moving from the minor leagues into the majors, where you are confronted with the glare of publicity at every stage.

JJM Did Sam’s stylistic breakthrough occur while singing with the Soul Stirrers?

PG Yes, although his performance of “How Far Am I From Canaan?” at his first Soul Stirrers session is a pretty good indication that he had achieved a style of his own with the QCs. That performance features a fully developed Sam Cooke style, although Art Rupe, the owner of Specialty Records, didn’t much like it and never released Sam’s original version. But Sam’s performance differed radically from the way Harris would have sung it and I think represents pretty accurately the way Sam sounded with the QCs. He developed his yodel in 1953, which is what distinguished his sound most of all stylistically — it became an almost all-pervasive mannerism, particularly in his early years in pop music. It was probably an adaptation of Harris’ yodel, which was more of a falsetto leap, something that was natural to Harris but wasn’t natural to Sam. So Sam created this kind of ululating “Whoa-oh-oh” sound as a substitute.

JJM He was also incredibly successful as a communicator. You point out that he sang so directly to his audience that they couldn’t help but feel as if he were singing just to them.

PG Yes. To go back to what we were taking about before, that is the one element that can never be taught or learned. You either have it or you don’t. One of Elvis’ earliest influences, Jake Hess, the great lead singer with the Statesmen gospel quartet, told me there were lots of singers more virtuosic than Elvis Presley, but there were none who could communicate with an audience the way that Elvis did. Sam Cooke had that same appeal, where every member of the audience, male or female, felt that they were being sung to directly. Even on record, there is that same sense of warmth and communication. For instance, R.H. Harris is a great singer, and you can’t listen to him without being moved, but it is a different kind of communication than Sam’s in that he simply doesn’t have that kind of warmth. Johnnie Taylor was a great singer who actually sounded almost identical to Sam, but Sam’s criticism of him was that there was always a certain coldness to the way he connected to his audience, both in person and on record. Not everyone would necessarily agree with that, but the point is that there is this kind of calculation that is very much a part of a singer’s appeal to his or her audience.

JJM What was his stage presence like while he sang with the Soul Stirrers?

PG He was a standup singer. The Soul Stirrers were a group of standup singers who never went in for acrobatics or showmanship in the way that, for example, the Pilgrim Travelers or even the Five Blind Boys, who, despite being blind, performed with tremendous drama and showmanship. On the other hand, starting with R.H. Harris, the Soul Stirrers presented themselves as standup singers, and that is the tradition in which Sam grew up, and it continued to be the centerpiece of his appeal. A contemporary of Sam’s, Jackie Wilson, performed with an incredible amount of showmanship, but Sam’s approach was to stand up at the mike and put everything into his articulation of the words, communicating with the audience just by the intensity of the way that he sang.

JJM Jackie Wilson’s approach seemed to be more one of “in your face,” which was probably more threatening to white society than Sam’s approach.

PG To a degree that’s true, but remember that Jackie Wilson had a lot of crossover hits, and was very ingratiating to a mixed audience. I would say that James Brown was more threatening in that sense. His shows of the mid-sixties were the greatest theatrical experiences I ever had — they were comparable to an August Wilson play in their scope, and almost exclusively performed before a black audience. Jackie Wilson’s showmanship is what got him back on Ed Sullivan seven or eight times at a time when Sam, for whatever reason, rarely appeared on Ed Sullivan. It may have been that appearing on the show required a bargain Sam was unwilling to make.

JJM When did Sam Cooke begin looking beyond gospel music?

PG The success Ray Charles had with “I Got a Woman” in 1955 had a cataclysmic effect on both the gospel and R&B worlds. Charles’ recording offered an opening for vocalists to present music in a new way. “I Got a Woman” is based on a gospel number, “It Must Be Jesus,” and the recording caused a tremendous stir at the time in both the sacred and secular worlds. Ministers were preaching against this “sacrilege,” but it offered a commercial and artistic opportunity for singers that simply could not be ignored. The effect it had on Art Rupe, the head of Specialty Records, was not to change the sound of the Soul Stirrers, but to seek out his own Ray Charles. Ultimately the person he found was Little Richard, who sounded very much like a combination of Alex Bradford and Marion Williams, with his ecstatic whoops but very secular message.

By the end of 1955, Little Richard was a pop star in that crossover mode, and that’s really when the pressure came down on Sam to go in that direction. The pressure came from three different directions. From Bumps Blackwell, who was his A&R man at Specialty; from Bill Cook, the Newark disc jockey who saw enormous crossover potential in Sam, and who functioned as his manager of sorts in 1955 and 56; and from J.W. Alexander, who felt that gospel was only holding Sam back in what he could ultimately accomplish. But Sam wrestled with this for at least a year-and-a-half, and it represented a rare moment of self doubt, because the thing that held him back was not so much religious inhibition — after all, his father had always taught him that a person is not “saved” by what they do for a living — but rather an uncharacteristic concern about whether or not he could make it in the secular world. What if he crossed over and didn’t make it? Could he ever go back? I think that kept him on the fence for a long time, but eventually he made the decision.

JJM You wrote that “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” by Lloyd Price — released by Art Rupe of Specialty — was the first breakthrough R&B song, and white record stores began to carry it because, according to Rupe, “Market demand dictates where the product goes.” How soon after this did record companies recognize this could become a full-fledged trend they could profit from?

PG I picked out “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” as a kind of signpost, but I’m sure there are others that can be cited. Certainly from that point on, you have this ineluctable drift toward what Elvis Presley started doing and what rock and roll is supposed to be. Around 1953, predictions started appearing in the music industry trade publications about a new type of music that eventually came to be labeled rock and roll, and symptoms of it were becoming more and more evident — although at the time it wasn’t possible to know exactly what form this new music was going to take.

What we are talking about here are two different types of crossover, the one with Lloyd Price to a white market, and the second, on the heels of that, the introduction of a pure gospel sound into R&B, which then benefited from its crossover into the white market. It was clear to everybody in the business at the time that something was happening, but they didn’t necessarily know where it was going to end up. Which is why this whole idea that rock and roll — which is really just a marketing term — was born on a specific date is silly because it was part of an evolution that grew out of the rise of the independent record companies, more money being available to teenagers after World War II, and a greater and greater degree of social mobility and, eventually, integration.

JJM On Sam’s effect on women who watched him perform, you wrote, “To J.W. Alexander, observing it all with something more than dispassionate curiosity, ‘The young girls would scream, the old women would scream. In the churches.’ What, J.W. naturally asked himself, if Sam were singing about love?” What did Sam have to overcome in order to move his music from the churches out into the streets?

PG He had to overcome an inner struggle and confront his fears about moving out on his own, the concern that if he were to fail, he might not be able to go back. He was writing pop songs from at least 1956 on — he recorded most of them in New Orleans at his first pop music session in December 1956. That was the session that his first pop release came out of, “Lovable,” which was released under the name of “Dale Cook.” But with the exception of “Lovable,” he had written the songs originally with the idea of having Bill Cook submit them to Roy Hamilton and the Platters, so he could become a pop songwriter, not a pop singer. Again, I think this is just part of that inner debate he was having with himself, and an uncharacteristic reluctance to make the bold move — a rare instance in his life where he didn’t simply say, “Ok, that’s it. I’m moving on to the next stage.”

JJM His decision to record under the name of Dale Cook was because of that risk. He felt if he failed on his own, he could come back as Sam Cooke.

PG Yes, which is an extension of that inner debate. I don’t know whether that idea was his or Art Rupe’s or someone else’s, but he somehow must have rationalized that if it didn’t work he could always say it was some cousin or some distant relative who had recorded that music!

JJM I suppose he could have possibly got away with that during that era.

PG Everyone knew it was him, and right away, because the recordings had all of his vocal characteristics and mannerisms, and it was a translation of the gospel single that the Soul Stirrers had out at the time, “He’s So Wonderful,” which was the highlight of every one of their shows. It was kind of a funny, almost quixotic attempt to escape detection, but, as J.W. eventually told him, he had to take his head out of the sand and “be Sam Cooke,” and that is who he became.

JJM There were issues around the songs that he wrote. While under contract to Rupe, songs he wrote were actually credited to L.C. Cook .

PG Yes, and that became the subject of a lawsuit and considerable controversy. He signed the songwriter’s contract the day before his first full scale pop session in June of 1957, which was probably the first real songwriter’s contract he ever signed. While he had signed off on songwriter’s rights as a member of the Soul Stirrers, this was a specific songwriter’s contract in which he gave half of his mechanical royalties to the publisher, which was essentially Specialty Records and Art Rupe.

Following the quarrel he had with Rupe over the sound of “You Send Me,” he and Bumps Blackwell left Specialty and, over the course of the summer, signed with Keen Records — which was not yet even a label, nor was it even named. By the time they put out his record in September of 1957, just a few months after that initial session, he had come to realize that he had signed away one of his principal sources of income. It was at that point that he recognized that songwriting and song publishing were the foundations for any money he hoped to make in the record business — something which people going into the record business today would be well advised to learn.

It was also at this point that he realized he could not get out of the songwriting contract he had signed with Rupe, but, of course, he knew it was only “Sam Cooke” who had signed that contract. In other words, the agreement required only Sam Cooke to share songwriter’s royalties, and because no documentation existed to show he had written these songs, he very conveniently “remembered” at this point that it wasn’t he that had written “You Send Me,” but rather his brother, L.C. A lawsuit that went on for close to a year ensued, and eventually authorship of “You Send Me” was awarded to L.C.

JJM When he left Specialty, why did he settle on Keen Records rather than a more established company?

PG Essentially there had been a struggle over who was going to manage Sam Cooke. Bill Cook believed that he was Sam’s manager right up until the time Art Rupe gave Sam’s recording contract to Bumps Blackwell, which in effect made Bumps Sam’s record company. Bumps then marketed that contract to John Siamas’ unnamed label, doing so in exchange for a high-level position with this new label, one that he considered to be an ownership position — though actually didn’t turn out that way for him. But he sold Sam on the label, so essentially it was Bumps consolidating his position with Sam, not just as his A&R man and producer, but as his manager as well. He felt they would have their best shot at success by going to this new label because they would get all the company’s attention in the way of promotion. But the move they made was done as much in support of Bumps Blackwell’s career as Sam’s.

JJM You wrote that Sam told his brother, “If you had all that slick stuff in your hair, the white man was going to think you were slick, he wouldn’t trust you around his daughter.” Sam felt that not appearing threatening to whites was a key to his success, didn’t he?

PG He felt that was one key to his success, yes, but another aspect was racial pride, pride in who he was and where he had come from. He cut his hair shortly after the huge success of “You Send Me,” stopped wearing it in a process and started wearing it natural. Which, of course, went directly against the prevailing trend of the time. So it was two things, really: racial pride and the idea of presenting himself in a clean-cut way. But in general, Sam always tried to present himself as someone who the white man would not be afraid to invite into his home, because then his records would also be welcome in those homes.

JJM He also tested limits on segregation quite early. As an example, he drank from a “whites only” drinking fountain in Birmingham early in his career that resulted in a police assault.

PG Yes, and around the same time, he went into a “whites only” park in Memphis while he was there with the QCs, and got picked up by the police.

Both of these incidents represented the same thing, and the disrespect and racial indignities he suffered were a difficult thing for him to contend with all his life, not just when he was eighteen or nineteen years old.

JJM He also refused to play separate performances for blacks and whites. Was he among the first performers to take this stand?

PG Sam was an emotional person who not only experienced and thought about things deeply but also read widely, which served to broaden his horizons. He found the conditions under which a person of color lived at that time — whether they were traveling widely as he was, or if they were simply living in a brownstone on the south side of Chicago — increasingly unsupportable. His experience was not unlike that of James Baldwin, someone who was not just a contemporary but who shared much the same experience, as a preacher’s kid, and someone that Sam eventually came to know. The point is, he felt the experience very deeply.

In 1961, Sam refused to play a show in Memphis where the seating was not only divided, but heavily restricted as well. The NAACP called these conditions to the attention of Sam and Clyde McPhatter, who were the headliners on the show, and they refused to play despite threats and intimidation. The specific threats to Sam were that his car would be seized or that he would be thrown in jail, but he and Clyde still refused to play under those conditions.

JJM Did he have concerns about how his stand on an issue like this could potentially alienate his white audience?

PG Yes, he cared very much about that. This was a situation where his concerns as a human being simply overwhelmed the way in which he approached his role as an entertainer. He was always concerned about alienating a substantial part of his audience, and some of the early pop work he recorded — like “You Send Me,” for example — were bleached-out versions of his gospel style, and this was done very intentionally. The majority of his early hits — whether on Keen or RCA — are essentially inoffensive novelty songs that feature very little of the gospel sound on which his style is based.

It wasn’t until he recorded “Bring It On Home To Me” in 1962 that he began to restore some of that explicit gospel sound to his recordings. I mean, it was always there in his live performance, because he continued to play predominantly on the “chitlin’ circuit.” But at the same time, he calculated the effect that his music had and attempted to record it in a way that would appeal to the widest possible audience. His idea was to appeal on a universal level without selling out, but you can see the calculation and the extent to which his own sense of dignity was offended in Memphis — measured by the fact he was willing to take a stand in a situation where he risked serious financial consequences and the alienation of a large part of his audience.

An interesting footnote to the Memphis story is that in its immediate aftermath, the next R&B act to play Memphis was Ray Charles, who had just done a similar thing in Augusta, Georgia, where he refused to play for a segregated audience. So that when Ray Charles came to Ellis Auditorium that summer, it was the first fully integrated show to play there. This is one of the few instances where you can point to the direct result that came out of that kind of protest.

JJM Sam Cooke was incredibly likable, but there is a side of him that is very hard to understand. He had great concern for so many people, yet treated his wife like hell. To put it mildly, he was a terrible husband.

PG I’m not sure that Barbara would say that she was a model wife, either.

JJM True, but he was the one who asked her to marry him, and this was after he had already fathered children with other women at a very young age. Why did he decide to marry Barbara?

PG You can see the how much she loved him from childhood on, and the way that she continued to try to find ways to reunite Sam with her and their daughter, Linda. But nothing seemed to succeed until she finally announced that she was about to move in with someone else, and then to her great surprise Sam finally proposed!

I’m not trying to defend Sam’s actions, but I would say that this is just one more example of the contradictions that exist in human behavior. In every one of us — sometimes in more extreme forms than others — there are elements of ourselves that are definitely at odds with the elements that we would choose to represent us. In Sam’s case, this was certainly one of them. But I should point out that it is more rather than less characteristic of the entertainer’s life, black or white, sacred or secular.

JJM Yes, and the preachers as well. The Reverend C.L. Franklin, for example, had similar issues.

PG Sam wrote an almost heartbreaking idealization of domestic life in “Nothing Can Change This Love,” a song that appears to present a perfect kind of love yet is totally undercut by the way he presents it. In a way it’s all about the distance between real life and the idealized version. I’m not trying to defend Sam’s behavior, but I think he was genuinely torn. He wanted that idealized domesticity, but it was certainly not the way he led his life or the way that he treated Barbara, and at the end of his life, I don’t think he honestly knew which way to go. While he had a commitment to a sense of family — particularly to his daughter Linda — his life and Barbara’s were certainly going in opposite directions.

JJM This is in the category of psycho-babble, but isn’t it also possible that he had issues with Barbara because his father didn’t approve of her?

PG No, that is not where I would go with it. Sam’s father was very stern — but also very fair — and his stern side led all of his children to rebel against him in one way or another. But I don’t think that had anything to do with Sam’s marriage.

In most respects, Sam had a pretty sure sense of where he wanted to go, but not in his relationship with Barbara. I really do think that he retained a love for her right up to the end, but it wasn’t the kind of love that could sustain itself in real terms. So I’m not sure he knew exactly what to do. I think he was definitely exploring the idea of divorce, but, you know, it was like so many marriages that continue because neither party is quite prepared to leave, and I would say that is pretty much where Sam and Barbara were at the end. From the standpoint of who wanted what, I think Barbara would have given up virtually anything for Sam’s love and approval, for a place in his life.

JJM Another interesting aspect of this story was the direction taken by Allen Klein, a brilliant strategist and business person who entered into Sam’s life and negotiated a groundbreaking agreement on his behalf with RCA Records. You wrote that the deal was “virtually guaranteeing a label commitment that no R&B artist other than Ray Charles had ever received.” Was this deal a template that other artists and labels would subsequently follow?

PG I think so, yes, although I am not the person to describe it because I never studied it enough to have a definitive answer. But Allen certainly sought to follow it in a variety of ways, including his subsequent work with the Rolling Stones and Beatles.

JJM Basically, he set up an independent record company that was distributed by RCA. I was frankly surprised that this deal was the first of its kind in the record business…

PG It may not have been. Somebody told me that Paul Anka’s deal with RCA — which was a production deal — provided a precedent for this and was the reason that RCA could agree to it, although I could never confirm that. Even if there was a model for it, though, I don’t know of another deal quite like the one Klein worked out for Sam, just like I don’t know of another deal like the one Ray Charles had with ABC.

JJM The deal seemed to be a huge risk for the RCA executive, Joe D’Imperio, to take.

PG I would say that it was done on the basis of D’Imperio’s belief in Sam. An interesting thing about the way in which Allen Klein works is that, much like Colonel Parker, his dealings were always based on personal belief, long-term commitments, and close associations. The people he dealt with thirty and forty years ago continue to be the people with whom he deals today. He never could have made the deal with Bob Yorke, the RCA executive who, according to Sam, was not returning his phone calls at the time. When Yorke was replaced, D’Imperio came in, and he and Allen hit it off from the start, because they both believed in Sam. Allen was indefatigable in his advancing of Sam, and if D’Imperio had not been receptive to the approach he was advocating, he very likely would have taken Sam to Columbia Records.

JJM Near the end of his life, Sam made a triumphant appearance at the Copa — which was quite a different result from the first time he appeared there. At the time, he was talking about his interest in continuing to sing, but also making some business ambitions known as well…

PG People talk about bifurcated personalities, but in Sam’s case you would have to talk about trifurcated, quadrifurcated, or even twenty-furcated! His ambitions seemed to go in every direction. I always remember how my mother used to tell me when I was a kid that I couldn’t do everything, and I was highly indignant, because, why not? All these years later I’m inclined to agree with her, although I guess I’m still a little bit indignant. Sam, though, was someone who continued to believe he could do everything, from playing the Copa and Vegas and making movies to running his own record company. His announced intention at the end of his life was to get off the “chitlin’ circuit.” He dismissed his band and began to cut back on his personal appearances, restricting them to the supper club circuit, and he had also signed a movie contract with 20th Century Fox.

Dick Clark asked him at one point what would give him the greatest satisfaction, and he said it would be if all the artists he was associated with had hits. That was part of his plan: to concentrate more and more on SAR Records, the company he and J.W. Alexander owned, focusing in particular on the Valentinos — Bobby Womack and his brothers — who he believed had the potential to become big pop stars. But at the same time, he was going in all these other directions as well. The last night of his life, he had dinner at Martoni’s with Al Schmitt, his A&R man at RCA Records, and they talked about a gut-bucket blues album he wanted to make, along the lines of Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and John Lee Hooker. So he was not going to limit himself!

JJM It is believed that Sam was killed during the early morning hours in the office of a Los Angeles motel. He struggled with the motel manager, Bertha Lee Franklin, after being robbed by the woman he was in the motel with. Franklin shot Sam as he apparently lunged at her. Were you able to uncover any new information about the circumstances of his death?

PG Not really. I had access to the private investigator’s report, which had never been available before, and while a good number of additional details were either brought out or confirmed as a result of this access, there didn’t seem much doubt that the official story of his death was fairly close to the truth. The way it happened was one of the ways in which Sam led his life. It wasn’t a contradiction, in terms of either where or how it happened. Sam was enraged because of the way he felt he had been “played,” and he just wasn’t going to accept that kind of treatment. All of the circumstances of his death conformed to the view of virtually every person I spoke with to whom he was close — I mean, it conformed to their view of Sam. As J.W. said, it was just a tragic waste. At the same time, within the broader context of the black community as a whole, almost no one believed he died that way — and they still don’t — because Sam was such a shining light. It couldn’t have happened that way because it shouldn’t have happened that way.

JJM Allen Klein suggested that Sam was not killed by an act of adultery, but was a victim of a violent crime, which is the view many people wanted perpetuated.

PG Allen’s point was simply to shift the emphasis for a variety of reasons — public relations, for one — but also because he loved Sam and truly believed that Sam was not so much the perpetrator as the victim.

JJM He had an awful lot of alcohol that night…

PG Again, you can see a similar reaction when he was turned away from the motel in Shreveport, so I don’t know that alcohol is the answer so much as Sam’s rage at the idea of being treated in this manner, of being disrespected in this way. In Shreveport he absolutely refused to leave, he just kept screaming at the night manager of the motel. His brother Charles, who was a very tough guy, was telling Sam they had to go. So was S.R. Crain, his road manager and the founder of the Soul Stirrers. Barbara was telling him they needed to get out of there because these people were going to kill him, but he just said, “They’re not going to kill me. I’m Sam Cooke.” Her reply was, “Honey, to them you’re just another nigger.”

The point is that in that situation he just flashed, and while I don’t mean to compare the seriousness or gravity of the two situations, he flashed at the Hacienda Motel in pretty much the same way. His father had taught him, his father had taught all his children, never let anyone disrespect you on the basis of color, economics, or anything else, and Sam always stood up to people, he always stood up for himself on that basis. There were numerous other instances where you could say his behavior was reckless in that regard. If he had been killed in Shreveport, he would have been seen, correctly, as a martyr of the civil rights movement — but it would have been for much the same reason.

.

.

___

.

.

“It didn’t matter who he was up against, because he didn’t do it as a competitor. All these Baptist sisters would sit down at the front, and they would scream. We would laugh at them because we were kids, but they were serious. They would yell things like, ‘Sing, honey. Sing, child,’ and I often wondered what was going on in some of their minds. Maybe I didn’t need to know. But you know what? Sam never allowed it to distract him. If he saw he had your attention, he could sing directly to you and almost be whispering. And when he got through, you would feel that he was talking to no one else in the room but you. [But then] the whole building would go up in smoke!”

– Mable John, sister of “Little” Willie John

.

_____

.

Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke

by Peter Guralnick

.

.

___

.

.

About Peter Guralnick

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

PG Probably both my father and grandfather, for a variety of reasons — mostly because they represented a kind of certainty, uprightness and character, as well as a sense of exploration and an openness to self-expression that I very much admired.

.

.

Peter Guralnick is widely regarded as the nation’s preeminent writer on twentieth-century American popular music. His books include Feel Like Going Home, Lost Highway, Sweet Soul Music, Searching for Robert Johnson, the novel Nighthawk Blues, and a highly acclaimed two-volume biography of Elvis Presley, Last Train to Memphis and Careless Love.

.

.

__________

.

.

This interview took place on December 5, 2005, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Arthur Kempton, author of Boogaloo, and Dixie Hummingbirds biographer Jerry Zolten

.

.

# Text from publisher

.

.

.