.

.

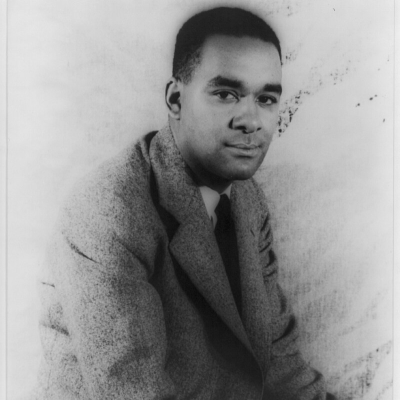

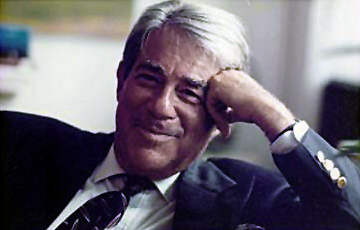

Peter Levinson

_________________________________________

Nelson Riddle will forever be linked with the music and recordings of such unforgettable vocalists as Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Judy Garland, Rosemary Clooney, Linda Ronstadt, and dozens of others. Riddle not only helped to establish Nat “King” Cole’s career in the 1950s, but was also a major participant in reviving Sinatra’s career. He served as arranger of many classic Sinatra albums, including Only the Lonely and In the Wee Small Hours.

September in the Rain is the first biography of the most highly-respected arranger in the history of American popular music. Peter Levinson’s book explores Riddle’s inspirations, career and creative genius, discussing every period of the arranger’s life, including his troubled childhood in New Jersey, his years with Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra, and his collaborations with Cole and Sinatra.

Levinson is the author of Trumpet Blues: The Life of Harry James, and is currently working on a biography of Dorsey. We are proud to feature him in our exclusive interview on the great American arranger, Nelson Riddle.

Interview by Jerry Jazz Musician contributing writer Paul Morris

.

.

___

.

.

JJM I enjoyed reading your book, and wanted to ask you why you chose to write about Nelson Riddle? What is it about him that secures his place in the musical pantheon?

PL He was the man behind the singer, at least that was his musical image. When Frank Sinatra died in May, 1998, it occurred to me that Nelson Riddle was a very important part of his musical career. I like to think he was the musical architect of Sinatra’s comeback in the early 1950’s, and that he was deserving of a book — a real study of his life and his contributions. All of his six children were of help to me and were quite candid about their father, the good things they remembered as well as mistakes he made.

JJM Would you say Nelson Riddle made a lasting mark on the musical landscape?

PL I would say yes and no. We are now in the age of Eminem. Rap and hip-hop are the predominant musical genres of popular music. There is no melody. Therefore, a man like Nelson Riddle would have no place in today’s music. However, when you look at the overall story of American popular music, I think Nelson Riddle probably stands out as the foremost arranger in the history of this genre. He could write uptempo arrangements like nobody else, and he could also write very mournful and meaningful ballads. He had great versatility. As an example of the lasting quality of his music, the album with the five-volume George Gershwin Songbook, which he did with Ella Fitzgerald in 1959, even today sells about 40,000 copies per year. That is quite extraordinary, especially since it’s an item that probably sells for fifty dollars. He did 16 albums with Sinatra for both Capitol and Reprise that also continue to be very strong-selling items. This is evidence of enduring, quality music.

JJM One revelation in your book was the important influence of Tommy Dorsey on Riddle.

PL Yes, the musical discipline of Tommy Dorsey, that was such an ingredient of everything he did, was something that Nelson grabbed on to. As an arranger, Dorsey knew what he wanted and Nelson had to deliver a high standard of arranging. As Bill Finegan pointed out to me, playing all of those Sy Oliver charts gave Riddle the sense of how to write very dynamic arrangements, which he did about ten years later for Sinatra.

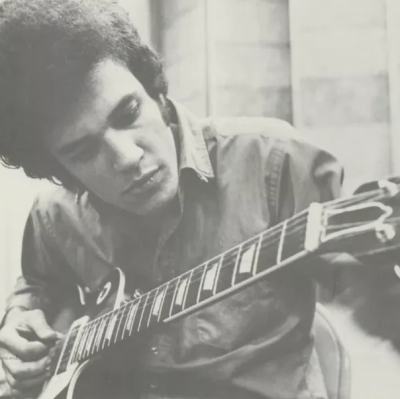

JJM That is quite a range, from Oliver back to Fletcher Henderson and the roots of jazz. One of his first big successes as an arranger on the national scene was on Nat Cole’s “Mona Lisa.”

PL There is an interesting story connected with that recording. At the time, Bob Bain was a very highly-sought-after guitarist. He came to Nelson’s house in 1951 and was told by Riddle about a recording session that he was writing an arrangement for Les Baxter. Baxter would then present the arrangement to Nat Cole to record. Nelson was a fairly good piano player, and Bob asked how the melody went. Riddle said it was a tune that Jay Livingston and his partner wrote and it is in a movie of Alan Ladd’s called O.S.S. Riddle began to play it on the piano, and Bain pulled out his guitar and played three or four chords. Riddle told him he really liked what Bain was doing, and said he wanted to use it in the arrangement. Those are the chords you hear to open “Mona Lisa” before the strings come in. That is how the song was arranged.

JJM He went on to do a large number of recordings with Nat Cole, 253 to be exact. I think that some readers of this book may not be aware of what the role of an arranger was in the 1950’s, what the working methods were and the sheer amount of work there was for people with his abilities.

PL In the 50’s, we could say it was part of the golden age of the tradition of American popular music. In other words, you had great ballads, great singers and songwriters who were constantly writing new material. It started with Irving Berlin and Cole Porter and George Gershwin and continued with great practitioners like Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen. Vocal records sold more than instrumentals — they always have and always will. After Riddle did his work for Capitol with Nat Cole, he was hired by Capitol to write arrangements for 22 other singers. That was before Sinatra really put him on the map. Working with Cole got him work within Capitol but it shows how much work there was. I think Nelson’s great talent was that he could work off a melody and work on using its strengths and highlight the important elements of a song to make it more dynamic and heart-rending. With singers, he was able to write to their strengths. He could write arrangements that would enhance the performance, and provide a setting to make the audio version more palatable to the listener, while at the same time showing off the strengths of the singers. He would also hide the fact that singers didn’t have a great range or great time. Dean Martin, for example, had very wobbly time as a singer, but Riddle wrote an uptempo album called This Time I’m Swinging, that was written in such a way that Martin couldn’t miss. He could easily come in at the right place. Riddle’s work was extremely versatile.

JJM You made an interesting point later in the book about writing for Eddie Fisher

PL Yes, Fisher had dreadful time. Dean was much better in that way and he was a better singer than Eddie was too. Nelson knew what to do, though. He wasn’t hot on working for Eddie Fisher, but he knew how to make Fisher sound decent, at least a lot better than he really was.

JJM Probably the biggest fame of Riddle’s career were his recordings with Frank Sinatra. Could you talk a little about that musical collaboration and how they got along as personalities?

PL Their first date together was April 30, 1953, almost 50 years ago. The first time they worked together, Alan Livingston talked to Sinatra suggesting this guy who they had success working with Nat Cole. Sinatra said he didn’t know who Riddle was, and he wanted to continue to work with Axel Stordahl, with whom he had done wonderful collaborations on Columbia Records. The first two records for Capitol with Stordahl didn’t do particularly well. Billy May was supposed to be the arranger on a date with Sinatra, but was called out of town to work with the new big band he was leading at the time. Capitol was behind May’s band and insisted he do the dates on the road. The date was set though, and musicans were hired, so Capitol hired Nelson as a ghost writer. He was asked to write two arrangements in the vein of Billy May’s “slurping” sax sound. Nelson could supply that and did. Then he wrote two creations of his own, looking to showcase his own kind of writing. Those tunes were “I’ve Got the World on a String,” and “Don’t Worry About Me.” Of course, those two tunes and the versions written by Nelson Riddle became keynotes of Sinatra’s career. “Don’t Worry About Me” was not released for a year and became a big hit for him. “I’ve Got the World on a String” was a song he kept in his repertoire throughout his career, and was often used as an opener for his concert dates in the 70’s and 80’s.

Working for Sinatra was not an easy task. You had a man with a very demanding nature who had tremendous mood swings. You never knew how he was going to behave or how he was going to react to the music. On a few occasions he didn’t like the music and just walked out. He had his own way of doing things, and that was very difficult on Nelson. It contributed a great deal to Riddle’s drinking. He used to go to bars alone after a session with Sinatra, and eventually it took a great toll on him. He developed liver trouble and later on died of that liver condition.

JJM When I was reading the middle part of your book, his personal difficulties were in the foreground so frequently, but having his music on reminded me how much joy and humor and love there was in his music

PL He could deliver those things musically, joy and humor and love, but he couldn’t handle life, his responsibilities, his children, his wife. He didn’t know how to handle that part of his life. As his daughter said, he knew how to arrange and conduct a 47-piece orchestra, but he didn’t know what to do with six children and a wife. I think that pretty well sums it up.

JJM You have some interesting ways of describing his work, one of which was, “He had a very muscular way of writing.”

PL Yes, he loved the use of brass, something that was left over from the Sy Oliver/Tommy Dorsey way of presenting big band music. He showcased the bass trombone, muted trumpet and flute, and used big bass lines. It was a very dynamic and modern way of writing swing music. Essentially, swing was the basic element of his music, but his harmonies were a lot more modern.

JJM You quote him as saying that film scoring was his favorite musical endeavor.

PL He would have loved to do that forever. He enjoyed working with a big orchestra. The problems were, I feel, the financial pressure he felt and then the change in music, which provided less film scoring work opportunities overall. He had to keep making money. Mancini could write any kind of a score. For instance, a little silly refrain with a clarinet or flute like the “Baby Elephant Walk,” and then he could write a great love song like “Moon River” or a comedic theme like “The Pink Panther.” But, Nelson didn’t have that ability. If Nelson had devoted more time to thinking about what he was going to write for a movie, he could have come up with better material as a composer. But because of the pressure to make money, he took too many arranging jobs that didn’t leave him with the time to sit down and concentrate on writing a theme for a movie or writing incidental music for a score.

JJM Could you name any Oscar nominees, winners, or other movie scores that you think are still worth listening to?

PL I have heard the first Oceans Eleven score, and I think that showed a lot of versatility in his writing. I don’t think that has ever been put on a record, as a matter of fact. In that, you hear some neo-Count Basie writing. He did some funny things where he had a scene with a stripper — his arrangement for Sinatra’s “Tender Trap” — and put it into a tempo for the stripper while she takes off her clothes, pretty good evidence of his writing versatility. He wrote a wonderful arrangement for Dean Martin, “Ain’t That a Kick in the Head,” which was featured in that movie. The El Dorado score from the John Wayne picture had an interesting use of guitars. The Great Gatsby also, with “What’ll I Do?” If a person buys a video version they won’t hear that because Parmount had Nelson do the score, but in the video version, Irving Berlin didn’t lend use of it. They had to take it out and use library music instead. For the movie Rough Cut, he wrote some wonderful arrangements for Duke Ellington songs. But, because he went up to the Academy and told his colleagues that it should award only one Oscar, and that the award should be only for an original score, not adaptation, he kind of shot himself in the foot. I think he certainly would have been nominated for that score.

JJM Is the Rough Cut soundtrack available?

PL No, it is not. I am hoping to be doing an album for Capitol of Nelson Riddle music from all his various labels, to be released at the same time as the paperback version of my book. If we make this deal, I am going to see if I can get some of the Rough Cut music from Paramount, because it has never been released as an album.

JJM I was intrigued to read about that music.

PL The movie is on television periodically. The Ellington songs are showcased so brilliantly by Nelson’s arrangements in the picture.

JJM An interesting anecdote in your book is that in his declining years Nelson Riddle actually worked for the Muzak Company.

PL Yes. That is evidence of how far down he had fallen. In other words, working for the Muzak Company was a job he had to take because he didn’t have a lot of work in the 70’s and 80’s.

JJM A couple more recordings I am wondering if you might comment on. Rosemary Clooney’s Love album, for one.

PL That is a magnificent album. As recently as four months ago she did an interview on a syndicated radio show, “Sinatra and Friends.” She said she felt that Love was the best album she ever did in her entire career. Nelson wrote all the arrangements, and she chose the songs. It really is the story of their love affair. There is a particularly good, obscure tune that was written by Carl Sigman called “How Will I Remember You?”

JJM The album by Dean Martin, This Time I’m Swingin’.

PL I really liked that album, recorded in the Sinatra vein. Sinatra was in the studio and kind of coached Dean on the singing. I think Martin succeeded and handled his job quite well on that album. Martin’s longest-running wife, Jeannie, felt that Dean’s work with Nelson Riddle was the best of his career.

JJM The recording of the Concert Sinatra….

PL That is a real masterpiece. I think that Sinatraphiles tend to obscure the worth of that album. I think it really works in the same vein as The Wee Small Hours of the Morning, and Only the Lonely. It is that good. I was fortunate to be up to see one of the sessions for that album.

JJM The great event of the last part of Riddle’s career was recording standards with Linda Ronstadt. Could you describe the effect that had on the musical world?

PL That really turned things upside down, because, here she was, the queen of rock during that period of the late 70s. For her to do, as she called it, “elevator music,” was a great surprise to that young audience, and they bought it. So many people around her, Joe Smith, the president of Elektra, for instance, were terrified that the records would turn off the rock audience. But, they bought those records. The three albums together sold over seven million copies and they brought Nelson back to a young audience. They hated what he had done with Sinatra, and a big orchestra was something they would have no part of, but suddenly he became somewhat of a hero to them because he worked with their favorite, Linda Ronstadt. It did an awful lot for bringing his career back into focus in the last three years of his life.

JJM Is there anything you would like to add about your book?

PL I think September in the Rain is the story of the age of the traditional American popular music as much as it is a biography of Nelson Riddle. It is also the story of his music and his troubled, very sad life. I think it is the story of the last era of the traditional American popular music with the great songwriters and singers. That is when Nelson was really in his heyday, from about 1951 until 1967, before he enjoyed the great resurgence of about three years in 1983 – 1985. Through my research I discovered Riddle and Sinatra were about to do a three-record set of standards he had never recorded before, but Nelson died before that could get started. It is a story of a great period of time, there is no question about it. There was a lot of glamour to it, and great music was created.

____________________

The Life of Nelson Riddle

by Peter Levinson

*

_______________________________

Nelson Riddle products at Amazon.com

Peter Levinson products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

Interview took place on April 19, 2002

photos from the book used by permission of the author

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Hoagy Carmichael biographer Richard Sudhalter.

*

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews