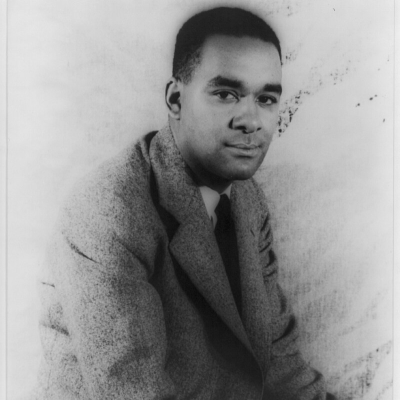

Nat Hentoff was born in Boston in 1925 and lived there until he moved to New York City at the age of twenty-eight. For many years he has written a weekly column for the Village Voice. His column for the Washington Times is syndicated nationally, and he writes regularly about music for the Wall Street Journal. His numerous books cover subjects ranging from jazz to civil rights and civil liberties to First Amendment issues.

He was jazz critic and an editor at Down Beat, and produced and wrote liner notes for numerous classic sessions, among them John Coltrane’s Expression, Andrew Hill’s Point of Departure and Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain.

Hentoff’s Boston Boy: Growing Up with Jazz and Other Rebellious Passions, is his memoir of growing up in the Roxbury section of Boston in the 1930s and 1940s. He grapples with Judaism and anti-Semitism. He develops a passion for outspoken journalism and First Amendment freedom of speech. He also discovers his love of jazz as he follows, and is befriended by the great jazz musicians of the day, including Duke Ellington, Lester Young, Jo Jones, Frankie Newton and Paul Desmond. Boston Boy,originally published in 1986, was followed in 1997 by Speaking Freely, describing his years in New York beginning in the 1950s.

Interview by Paul Morris.

________________________________

JJM I want to talk to you about your recently reissued book, Boston Boy, Growing Up in Jazz. It describes your boyhood in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston. It was solidly Jewish and very politically aware

NH Not entirely Jewish, there were some black folks up the street

JJM Your description of your coming of awareness in that neighborhood is often self-mocking. Did you find that hard to do, to describe some of your experiences that now seem silly?

NH They weren’t all mocking, by any means. I think any kid reacts that way, so I just rememberd how I felt.

JJM You were remarkably frank about your problems with your family and friends

NH Yes, but if you remember I had a great respect for my father. I got my whole concept of justice from him, not from my school books. I admired my mother, who at the time, as a woman in fairly traditional Jewish circles nonetheless broke the rules there, and insisted on saying the prayer for the dead for her father. So, it wasn’t all mocking, it wasn’t all negative.

JJM Could you talk a little about the variety of political radicals in your neighborhood?

NH In Jewish sections of Boston at the time, particularly Ward 12, where I lived, the overwhelming popular support was for Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He used to get 80% of the vote every time he ran. They were the conservative Jews compared to the very voluable and active members of the Socialist Party. There were Communist Party members and there were a few anarchists, although as far as I knew they were non violent anarchists. It was a very “social justice” kind of neighborhood, despite the fact that that was also the name that Father Coughlin chose for his newspaper, which promulgated every Sunday various anti-Semitic canards.

JJM Your description of your job working at Sunday’s Candies in Boston was in a lot of fine detail and humor as well. There you threatened to organize a strike to get increased wages

NH Yes, we worked very hard during the weeks before Christmas. We all went to school, so we worked nights, sometimes long nights and weekends, because that was the season when the very important part of the business came in. There were bulk orders from stores and factories, etc. We were getting 35 cents an hour, we being college and high school kids. I decided that was not fair, and that we ought to get 50 cents an hour. We chose to call the strike precisely about three or four weeks before the Christmas season, when the orders would come in, and we got our 50 cents an hour.

JJM Good victory!

NH I remember the boss coming in to see my father, during the threat, complaining that this ungrateful boy, who was making this large sum of money, was threatening the business. My father, who had organized a house painters union when he came to this country, did not show much sympathy.

JJM Another job you write about, which lasted a number of years, was at a radio station, WMEX, where you played jazz records and you wore other hats as well

NH Yes, I also did a folk music program at which Pete Seeger, for example, was one of the guests, and the boss decided I must be a communist, even though I was as anti-communist as you could be. Also, I did what everybody did at the station, I read the news, did sports. It was very valuable to me. We all did a lot of ethnic programming, because independent contractors would buy spec time on the station, and I did Italian shows, Jewish shows, and some wonderful black music, gospel music groups that came in once a week. It was especially valuable to me because I thought country music was “hillbilly”, but when I started to have to play Bob Wills and western swing and Kitty Wells and Ernest Tubb and Roy Acuff, I got an education.

JJM Besides in your neighborhood and at school, you describe in your memoir a lot of learning going on at jazz clubs

NH Yes. I started listening to jazz when I was about 11 years old, and that has been a basic part of my life ever since. I consider jazz a life force. Fortunately, because I was able to get the radio program, I got to know a lot of the musicians. We did remotes from the Savoy Café, which is where I spent most of my off time, and they would come up to the studio and I got to be friends with some of them, Rex Stewart, for example, and Duke Ellington was very kind. They were my teachers in the sense that, by contrast to the other adults I knew in school or in my family, these were people who, first of all, took risks every night. That was part of their vocation, and who therefore if were not irreverant, certainly were not obedient to authority, they were their own authority. They traveled a lot, so I learned a lot. They would come back from India or someplace and I would find out stuff I didn’t see in the newspapers. Most of all what I learned, because even at Boston Latin School, where I spent six years, and which was a very prestigious public high school I knew very little about Jim Crow. Thus, I learned a lot from them because many had come from the south or had traveled from the south. So I would say my post-graduate education in my teenage years came primarily from jazz musicians.

JJM You write particularly about Jo Jones as an important teacher in your life …

NH Jo took jazz to be religious vocation, if you were chosen, that is if you had the skills and the capacity to express yourself, feelingly and every other way that would make your music reach other people, then he thought that was almost a religious responsibility. I was an atheist from the time I was 13, but I knew what he was talking about, because he said it with such fervor, and he exemplified it when he played. And, more to the point, he was extraordinarily solicitous and caring of younger musicians, and he even took a couple of us lay-people under his wing. As I wrote in the book, he sat me down one day in the back of the Savoy and explained why jazz was such an important cultural addition to America, and such an important way of being, although he kept saying people had to be morally straight and live careful lives in order to be in physical and mental shape to play jazz. He was really concerned with jazz as both a moral as well as a spiritual and expressive form of music. So, yes, I was very impressed with Jo and was fortunate to get to know him later when I came to New York.

JJM There is a terrific story in your book that describes your dating a pianist who was admired also by a cop with a reputation for viciousness

NH It was a black cop, and at that point in Boston, it was almost like a southern city, because there were strict divisions between blacks and whites imposed by the whites. Even next to the Savoy there was an alley where cops would pick up people suspected of whatever burglary or whatever. Often there was a lot of bad physical stuff going on and this guy was known to be one of the worst, black though he was, because the people beaten up were almost invariably black. He was very interested in this singer, and I would occasionally walk her home. Then, as in the south, most of the musicians did not stay in the hotels downtown because they were not very welcome. They stayed in boarding houses or in private homes in the neighborhood. Frankie Newton, who was a wonderful trumpet player and person, and who often played at the Savoy, was a race man in the sense of the word, in that he knew black history and he was very outspoken in terms of civil rights, black rights, etc., but nonetheless, because he knew I might be in trouble with this cop, would walk behind us. He was a tall man, very imposing. He was there in case I needed any assistance. He was like riding stagecoach.

JJM Your book also includes a nice portrait of Paul Desmond …

NH Paul was an extraordinary person. People who know his playing must know the lyrical quality with which he played and the wit. My favorites were Charlie Parker and Johnny Hodges. Desmond was closer to Johnny Hodges than anybody else because he had that ability Ellington once said to me that if Hodges was playing a ballad and the men in the band, including Duke heard a sigh from the audience, as would be the case with Johnny’s way of playing, that sigh came into his music. Well, Paul had that ability too. He was a measured romantic like Hodges, not sentimental, but he really could sensuously and intimately get into your soul. He was also a very funny guy. He wrote very well. He unfortunately didn’t write much. He wrote a couple of pieces for Punch, the English humor magazine and a couple of others for the jazz magazines here, but he was a very witty writer as well.

JJM I think line for line the few album notes that he wrote were the best

NH That’s right.

JJM You write that you ended your relationship with him by giving a bad review to one of his albums

NH Yes, that’s one of the problems about becoming friends with musicians I remember at one point Whitney Balliett, who is a first rate critic, used to say that he wasn’t going to get to know them because he didn’t want the friendship to get in the way of the criticism. But then even he decided he wanted to write profiles and you have to know sombody to write the profile. In Paul’s case, he put out an album with strings, and I just didn’t think it was all that hot, and I was reviewing records for Downbeat at the time, and I said so. He took umbridge. But, toward the end of his life our friendship returned, and I think in retrospect, in view of the turn it took, if I had to do it over again, I would have let somebody else review that record, because I missed the friendship.

JJM Your book ends as you move to New York. Your next memoir was Speaking Freely, which was released several years ago. In rereading some of your other books on jazz, I was struck by how familiar many of the anecdotes and remarks were. My first reaction was that these are full of over-familiar tales and I have heard these quotes 100 times, but then I realized that they weren’t recycled in your books, because they first appeared in your books!

NH Oh, you mean you have seen other people use them?

JJM Oh, sure. A lot of the excerpts from Hear Me Talkin’ to You are seeded in practically every jazz history.

NH That was our intention, Nat Shapiro and mine. We wanted to do two things. The obvious one was to show the history of the music, unfiltered by even us critics. Let the musicians talk for themselves. The other thing was that then, even among jazz aficionados, the notion was that jazz guys were not very articulate except on their instruments. They were considered almost quasi-primitive and we knew better, because we knew them. In that book, and also in a magazine that Martin Williams and I put together for a while called the Jazz Review, the rule there was, except for the editors, only jazz musicians could write. They did all the reviews, all the historical analysis, practically, with a few exceptions. Again, it would show how much they knew that we didn’t, but also to show how articulate they indeed were. The one mishap we had, which was totally inadvertent Gunther Schuller, who is a master analyst of music as well as a composer and conductor, did an admiring piece on Sonny Rollins, in which he detailed how Sonny improvised, almost bar by bar. Unfortunately, Sonny read it. Sonny, being self-critical anyway, was terrified for awhile because every time he started to play he was thinking of the analysis.

JJM In another of your books, The Jazz Life, you wrote that jazz had characteristics of a secret, elite group. You have a number of sociological observations about jazz. Would you say that jazz at the time you were writing in the late 50s was less marginalized as part of America?

NH I think I meant secret in terms of the public at large. Otherwise, as Phil Woods made this point a while ago, jazz was and is, even more so then, a family – obviously among the musicians. What is missing now in terms of a family, as Phil said, is in those days you could get on a bus with a band and the old guys and the young guys would be there and you would keep learning from the old guys, both in conversation and later on on the bandstand. I think there is less of that now because there are fewer places like big bands and jam sessions where that kind of mixture would take place. But, for the public at large, insofar as if they cared about jazz at all, which was not very much, it did seem like an elite society, and a rather forbidding one. I even heard a jazz writer say the other day, “You know, it’s complex music and it’s hard to get into ” That’s not true at all! If anything, if somebody has put that in your mind, I can see how that is difficult – but that’s not the point. The point is you open yourself to it. I once asked Ellington, what do you hope for in a listener? He said the last thing I want from the listener is somebody who is going to analyze what we are doing. I want the listener to feel what we are doing and to become part of the music, without having to analyze it. So, sure, the elite notion was maybe put in some motion by some of the writers, but I don’t know how it got around, but its still there to a large extent. One of the most encouraging things I have seen in a long time is in Sarasota, Florida, a jazz club there, and a wonderful woman named Nancy White has managed to have all the 5th grade students in the public schools study American history interlinked with jazz. They have jazz videos, recordings, musicians come and talk to the kids, and its natural then. They are not old enough to think it is forbidding or anything else. It is fresh to them. At least one of the classes has a fifth grade jazz band as a result of all of this.

JJM That’s interesting. I have a seventh grader, and I know he didn’t go through anything like that

NH Well, most kids don’t. One of the encouraging things is, I understand, is that other school systems are in contact with the Sarasota system, asking how they can start doing that as well.

JJM You were the editor of Downbeat in New York, you were writing liner notes and were acquainted with Miles Davis and Charles Mingus, living the jazz life full time. Was this a golden age for jazz?

NH I hesitate to say that because it implies that what is going on now is somehow of less interest. It was a golden age to me because I got to know these people very well, especially Mingus, who turned out to be a lifelong, very close friend. I got to know Miles very well until he recorded Bitches Brew, and I did not take to the electronic stuff. It’s like what happened with Paul Desmond – Miles cut me off entirely. I do think in terms of only this, in jazz and other forms of music as well, the difference between originals and originators. There are a lot of originators still in jazz, and always have been. The originators, like Bird, like Mingus, like Monk, Armstrong, like Lester Young – there were more of them then than there are now. It doesn’t mean that it won’t come flowering again. In that respect, I guess I would say it was sort of a golden age of jazz. But, my goodness, the important part of the music is to keep it alive and there are so many people doing that on a very high level. For instance, Joe Lovano, or Dave Douglas, and people coming along all the time, like Greg Osby. Then, you have somebody like Jim Hall who is both an original and an originator. I hesitate to use the term golden age in the sense that it was in the past and we will never get back there. John Lewis once said to me, in the 1950’s, for all we know, right now there is a bass player in some Bulgarian night club, who is going to be the next person who is going to turn jazz upside down like Bird did. You never know what’s going to happen. In Boston Boy, I make mention of something Bix Beiderbecke said to Jimmie McPartland, “You know what I like about jazz, kid? You never know what’s going to happen next.”

JJM One more question about the old days. You ran a record company for a couple of years, Candid…

NH That was a jazz fan’s fantasy come true. Archie Meyer, who was then a very well known music director for the Arthur Godfrey radio show and who also had his own record company called Cadence, a pop music label, with Andy Williams and the McGwire Sisters. This label did very well for a time. He loved jazz. He didn’t know much about it, but he decided he would make a contribution to it by setting up this label. This label was independent of Candid. He asked me to run Cadence, and I said I would be glad to do that provided I could do whatever I wanted, without worrying about the bottom line. I told him up front that what we were going to do is not likely to make much if any money at all. It could result in a modest return over time. He agreed with that and he never interfered. I have no idea of what he thought of some of the stuff we did. There came a time in the economy, at least in the economy of the record business, where his own label, Cadence, was not doing very well and he had to cut us off, which was perfectly understandable. I was grateful for the time we had to do what we wanted to do. In turn, my conception of an A & R man was to select the leader, but then the leader would decide all the rest. I would occasionally suggest doing a blues tune or something, but otherwise all I did was mark the time, send out for sandwiches and beer, and always, the leader determined what was going to be released.

JJM Some notable recordings are still available from that label, such as Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus, with Eric Dolphy.

NH Yes, there is an American record company named Artists Only, and they are releasing a lot of them through licensing from England. Alan Bates is the guy who owns the rights. I just got a fax from Swing Journal, the jazz magazine in Tokyo, and a jazz recording company is releasing them all over there. I remember that long after I left the label, musicians would tell me after coming back from Japan, they would go into record stores and see that all those old Candid recordings were still there, including a number of ones we never had time to release.

JJM So, you hadn’t even seen them yourself?

NH Not these, no.

JJM One project that I think is fascinating is the Pee Wee Russell and Coleman Hawkins reunion album.

NH Oh yes, that is something I always wanted to hear again. The original recording I believe was called Hello Lola, made in the late 1920’s – something like that. When we did the sessions, Coleman Hawkins, whom I always approached as if he were some sort of “lord of the manor” because when he came into the studio he seemed to be ten feet tall I didn’t often say much to him, but after one of the takes, he said to me, “You know those sunny notes that Pee Wee put in? He was playing those back in the 20’s, and they were right then!” That’s one of my favorite records. Nat Pierce was the pianist, and I think he did the arranging too. Nat never got as much credit as he should have. He could do anything, including swing itself, and make his charts conform to the strengths for whoever he was writing for.

JJM That was a great service to get both of those musicians to record at that time.

NH Yes, although somebody asked me, I think it was Swing Journal, what is your favorite records of the ones you had something to do with? I could list a lot of them, the Mingus, and Cecil Taylor, all kinds of things, but I guess if I had to list one it would be Booker Little, who died so young, and already was a trumpet player of the stature of Clifford Brown, and a composer who I think would have been one of the best. His lyrical quality, originality, the way everything worked together in a continually fresh way That album he did, Out Front, if I had to name one, would be one of them. That is out on Artists Only now.

JJM I have a couple questions about John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. You contributed album notes to some of Coltrane’s albums …

NH Yes, that is one of my favorite often repeated stories. Every time I would call him, we would go through the same routine. I would say to him that Bob Thiele, president of Impulse Records, asked that I do the liner notes on your new album. John would replay by telling me he wished I wouldn’t, because if the music doesn’t speak for itself, what’s the point? I would also say, “John, it’s a gig ” He would say, ok, what do you want to know? He was a very kind man.

JJM Where would you say this album stands among the great recordings of jazz?

NH It stands among them, just as some of his others do. This was a man who was always searching, and therefore always evolving. That is why in his live performances, some of which have been recorded, he could go on for an hour and a half on one song, because he was always looking deep, trying to discover what else could be said. A Love Supreme he was able to reach inside himself through his music. I never asked him about this, and it may be a wrong theory, but I think some of the parts of his recordings and his live performances that were like anguished or tortured shouts, was almost therapy, a self-cleansing in a way. It was all part of this ceaseless intent to do two things; number one to find out who he was in music and say so, and also something I couldn’t follow a lot, it was beyond me, because he had written a lot of Hindu philosophy, he had a conception of being a part of an organic world. I use this term with some diffidence because I am an atheist, but his music was all very “spiritual” to him, and to me, even though I should make that utter leap into this cosmos thing.

JJM As Coltrane progressed, especially right after that recording in the mid 1960’s, his solos got longer and the structures seemed to be harder to perceive. Albert Murray said that it is difficult to embrace chaos. Do you think he embraced chaos?

NH I have a lot of respect for Albert. I used to see him on the street when I first came to New York, and I went and listened to a half hour lecture, and it was always very instructive. But, Albert came up in the period of Basie and Lester Young and Duke and all that, and I don’t think he quite made the bridge. It was hard for me to make the bridge even to Bird, because I grew up with Johnny Hodges and Benny Carter and that kind of playing. But, if you don’t transcend, and not everybody can, what you grow up with is what stays with you. If I just want to listen to music for pleasure, I will listen to Lester Young and Billie Holiday and all those sorts of people But, John was not creating chaos, that would have absolutely appalled him, because he had this sense of the order of the universe that he was trying to be part of it through his music. I was once talking to Albert Ayler, who was for many people, including me, difficult to follow and could seem to be chaotic, and he said to me that the way to listen to him and to what some of the other people were doing was to just listen and open yourself to the whole experience, to the “gestalt” of it. Don’t try to find the harmonies, don’t try to wonder where the melody is going. If it reaches you emotionally, if you become part of it, then you are listening to it. For what it’s worth, I think that is one way of listening to a lot of Coltrane. It goes back to what Ellington once said, that if you start to analyze it like you are a musicologist or a critic then you are going to miss part of it, maybe the part that the musician most wants to transmit.

_______________

Boston Boy

by

Nat Hentoff

Nat Hentoff products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

Interview took place on November 20, 2001

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with cultural critic Stanley Crouch

One comments on “Nat Hentoff: on his life as a jazz critic, and memories of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme”