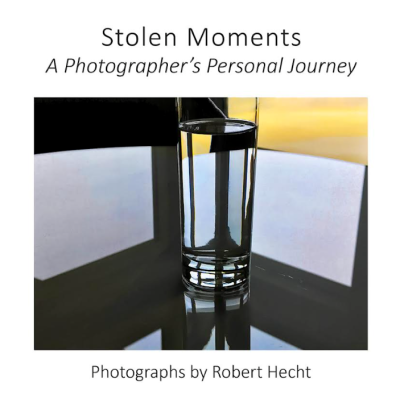

Loren Schoenberg

author of

The NPR Curious Listener’s Guide to Jazz

_________________________

Loren Schoenberg is a noted conductor, saxophonist and author who has appeared internationally and won the 1994 Grammy Award for Best Album Notes. He has recorded several albums with his own big band, and also with Benny Goodman, Benny Carter and Bobby Short. He is on the faculties of the Juilliard School, the Manhattan School of Music, Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Essentially Ellington Band Director’s Academy, and is program director of the Jazz Aspen Snowmass Jazz Colony and is Executive Director of The Jazz Museum In Harlem.

He is the author of The NPR Curious Listener’s Guide to Jazz, a book Wynton Marsalis describes as a “thorough guide to the music from a few basic perspectives: what it is and how it’s made, its history, the people who made and continue to make it, some suggestions on how to approach it — and a whole pile of ideas.”

A bright, thought-provoking conversationalist, Schoenberg joins Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in an interview covering his colorful experiences as a young man, his friendship with Teddy Wilson, his work with Benny Goodman, and the challenges jazz faces as a relevant musical art form.

*

_________________________

JJM What is your first memory of jazz, Loren?

LS I guess my first memory of jazz was hearing Louis Armstrong on the Ed Sullivan Show.

JJM Do you remember what he performed?

LS No, I can’t say I do. I really don’t have a first, bona fide jazz memory. Jazz just snuck up into my consciousness as part of the music I encountered as a kid. I do remember specifically how I got into jazz music, and how that happened, but it is not really what I would codify as a first jazz memory, to be frank with you.

JJM So, when you first saw Armstrong on the Sullivan show, had you already started an interest in jazz?

LS No, I didn’t know it was jazz that I was hearing.

JJM Could that have been the era of “Hello Dolly”?

LS That’s right, it would have been during the era of “Hello Dolly.” That would have been ’63 or ’64, and I would have been five or six years old.

JJM What instrument did you begin playing and at what age did you start playing it?

LS I began playing the piano when I was four years old. We had a piano in the house, which I was drawn to, and my mother gave me rudimentary lessons on it. She taught me as much as she could and then she turned me over to my piano teacher, who lived right down the street from us. I began lessons at age four.

JJM Do you remember the pieces that you played at that age?

LS Yes, I do remember. My mother had bought me a few nursery rhymes, little simple things on the piano that most kids play in the key of C. Then, when I went to take piano lessons, we began with a book that most piano students learned from. I think it was called “John Thompson Travelogues,” which were little itsy bitsy piano pieces, usually in the key of C, with the name of a foreign country in the title, and the music was supposed to be indicative of that country’s music.

JJM In retrospect, do you feel your mother had you take these lessons because she thought you had some musical talent, or did she do it to keep you busy?

LS As I say, I was drawn to the piano, so I think that was part of it, because I liked it and showed some aptitude for it. Most kids — and I eventually became that kid — eventually don’t want to practice or would rather be doing something else, but at that point I was drawn to the piano and the lessons were very helpful because they helped channel my nascent enthusiasm toward tangible goals.

JJM This would have been early sixties, which was right during the time that rock and roll was coming of age. Were you enticed by that music?

LS I knew that I never did like what was known as “rock and roll.” My relationship with it ended in 1961, when at age three, I won a Twist contest on my block. That was it. I had two older brothers, so I got all of the popular music of the time from them. My oldest brother was into Al Hirt and doo-wop groups, and my other brother was into the Beatles, and he had a band that played that stuff. Coming of age in the sixties, I never liked it, nor was I ever attracted to it.

JJM How about jazz?

LS I can’t say I was drawn to jazz, either. I was just on the piano playing things like the Godfather and Love Story themes. My awakening of something separate called jazz really came to me around age ten or twelve, and when I turned thirteen I got heavily devoted to jazz music.

JJM What happened then?

LS My father had old 78 rpm Al Jolson records. I didn’t know anything about blackface or Jolson, all I knew is that my father loved these records. I used to alternately play them and use them as frisbees. The records, as a result, didn’t last long. But I was quite entranced by the musical quality and the phrasing in these records. From Jolson, I became interested in musicals, specifically the Warner Brothers films. I enjoyed the Ruby Keeler films that Busby Berkeley choreographed. It was in those films that I was introduced to the music of the thirties. I was also quite touched by Frank Capra’s film It Happened One Night, which was the first time I had ever seen a film four or five times in a row. As I became more interested in film, my parents would take me to New York on the weekends, where I saw a film called Hollywood Hotel, which included Benny Goodman’s band.

At about this same time, I discovered that my hometown library had jazz records. From there I took out the Goodman Carnegie Hall album from 1938, and I just loved it. I memorized it. I soon discovered that the library had all kinds of odd records, and I began listening to trumpeter Booker Little records, and Tijuana Moods by Charles Mingus. I took these records out and listened to them. Then, in another library, the Ridgewood, New Jersey public library, while looking for information on Benny Goodman, I found a book called B. G. On the Record, which was written by Russell Connor. I subsequently wrote him, asking about Goodman records, and he sent me back some things that turned me into a record collector.

I started hanging out at the local Sam Goody record shop, and met people at the Goodman record bin who I had similar interests with. At this time, in 1971, Goodman’s pianist Teddy Wilson was playing local Jersey clubs. I couldn’t believe that the same pianist who was on my Benny Goodman records was playing fifteen minutes from my home town. So, I went to go see him, and my parents met him, and it was through him that I first met Benny Goodman in 1972, as well as Lionel Hampton and Gene Krupa. I was fourteen years old at the time. I guess it was kind of novel for them to have a fourteen year old fan. That was how my interest in jazz started.

JJM How old were you when you worked at the New York Jazz Museum?

LS That was 1972, so I was fourteen then.

JJM How did that work impact the direction of your career?

LS My parents were a bit skeptical about my interest in jazz, and the nightlife and musicians associated with it, but luckily the first two musicians my parents got to know well were Hank Jones and Teddy Wilson. Wilson was playing at the Cookery in New York, which was owned by Barney Josephson, who also owned Café Society. It was quite a place.

That night, somewhere in early 1972, Wilson mentioned to me that he was taking off early to play with the Benny Goodman Quartet, which seemed like a dream to me, because they hadn’t played together in years. That evening, Lionel Hampton was getting an award from the National Urban League at the Waldorf, and they were going to have the original Quartet, plus George Duvivier and Illinois Jacquet. He mentioned that and I went crazy! I asked my parents if I could go, and we asked Teddy if he would take me, and he said he would. Thank God that both my parents were very supportive and gave me their permission. I got all their autographs that night. Later, I noticed in the newspapers that there was a jazz museum opening in New York. I went in on a weekend and asked to volunteer, just as all this stuff was happening.

JJM And you took piano lessons during this time

LS My lessons with Teddy Wilson were very informal. They were more like being with someone who hung around, asking questions. I was there all the time, as opposed to sitting at the piano. They were pretty intensive. When I started working at the Jazz Museum, I met some very interesting people, including a man named Jack Bradley, who was an old friend of Louis Armstrong’s. He had been almost adopted by Louis. I met the writer Dan Morgenstern there, as well as trumpeter Ruby Braff. Braff heard me fooling around on the piano one afternoon, and he said I was pretty good but that I needed some help. He recommended a marvelous piano teacher named Sanford Gold, who was a legendary teacher not only for the piano but for technique, music theory and general musicianship. He taught the whole thing. Well, he got a lot of money, something like $25 an hour, which was a ton of money at the time. I told my parents about it, and while they thought it was a great idea, had reservations about the price. So, one weekend, my folks were in the city and came by the museum to pick me up. Ruby Braff and Jack Bradley came out to the car and told them how vital it was for me to study with Sanford Gold, and that if my parents couldn’t pay for it, they would. It was a very nice gesture, and it accomplished its goal, which was to make my parents realize that this was something very serious they were talking about.

JJM You wound up becoming the archivist and manager for Benny Goodman towards the end of his life.

LS Yes, that’s right. That happened about eight years later.

JJM That’s remarkable. What was your relationship like?

LS Basically, to make a long story shorter, I met Benny when I was fourteen. I went to his office and got an autographed picture. I think I made an impression on him because he didn’t have too many “wanna-be” groupies at that point. I got a phone call one day from Benny’s office, and by this point I knew the people who were playing with him. I assumed he was calling to have me play tenor sax — Zoot Sims or Scott Hamilton may have floated my name to him. I was so thrilled. Well, it turned out that he was not calling me for that. He had gotten my name from Russell Connor, the author who had written the book on him. Benny was about to donate his arrangements to the New York Public Library Performing Arts division, and he needed someone to write what he called the provenance, which was the accompanying literature for the donation. So, what happened was I wound up being paid by Benny Goodman to go to his office, spend all day looking through his original scores, select which ones I thought were the best, and then ask him questions about them. It was really like a fairy tale in some ways. This eventually grew to my becoming his personal manager, and from that grew to him actually using my band as his last big band.

JJM Earlier in the interview, you were talking about how you used to go to the theatre to see the movies and Goodman was one of the people you saw in the films, a man you admired, and here you are, managing his career. That is quite amazing.

LS It is, yes.

JJM Why did you decide to write the NPR Curious Listeners Guide to Jazz?

LS Not to be cute about the answer, but frankly they asked me to. I have been a writer for about eighteen years now, mostly of liner notes and extended liner notes, as well as a few chapters in a few books, but I had never written a book of my own, Some pretty good publishers had asked me to write, but I turned them down because I didn’t feel I was quite ready. I had been doing CD and book reviews for NPR for awhile, and I was recommended to do the jazz guide in their series called the NPR Curious Listeners Guide. I said I would do it. I thought it would be, for a first book, relatively easy, and of course I was wrong. It kicked my butt.

JJM Sure, there is a lot of work involved in this

LS A lot of work involved, yes. The work involved in a project like this has to do with editing — not editing words as much as editing content in the sense of, how can you pick the fifty best of anything?

JJM Are there any similarities between jazz improvisation and writing?

LS I have never really understood most of the analysis about that. I know they say that certain authors are supposed to be “jazz authors,” to the point it is accepted as commonplace. I don’t get it. Writing is writing. Music is music. Improvisation is improvisation. Composition is composition. I can see some links in terms of basic principals of narrative structure or of composition. Beyond that, I don’t quite get it.

JJM Yes, you hear a lot about how Jack Kerouac, for example, was somebody who supposedly wrote with the rhythms of people like Charlie Parker and Lester Young in mind

LS To be honest with you, I think people like Kerouac and specifically Allen Ginsberg at times had a mistaken understanding about what improvisation is and what it is about for jazz musicians. They tended to emphasize the mysterious, spinning out of thin air, “go jazz man go” thing. You go back to some of those Carl Sandburg poems of the 1920’s, and they come across as vestiges of noble savageism, even in the hands of people who loved black musicians and thought they were doing something good. I really don’t go too far with that, they are really separate disciplines. I would say in the larger compositional sense, how to organize things, yes, I can see it Beyond that, I really don’t get it.

JJM How important is communicating aspects of the music’s history to new listeners?

LS I think it is very important. However, I don’t think that getting a historical perspective is going to bring anybody to the music. I think one has to be seduced by the music. Jazz, as the critic Martin Williams noted many years ago, is essentially rhythmic. It entrances, it seduces through the rhythm and then one gets into the melody and the harmony and eventually into the totality of all three. I think for an inquiring mind, for a curious listener, I think the more you learn about its many contexts, the more one can bring to it. You can get into Louis Armstrong’s recording “What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue?” and it takes you everywhere from black Broadway to Broadway to Fats Waller to Andy Razaf to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. It takes you to discrimination between racial groups and within racial groups, because we know that the tune is supposed to be sung by a black woman who feels unattractive to lighter skin black males. I think the more one can place any given jazz moment in an interesting context is for the good, but I don’t think that is what turns anybody on to the music.

JJM As jazz has evolved and developed into different stages — genres within genres — what is the most radical transition between the genres, and what impact did it have on the art on a large scale.

LS I would say that the most radical transition was what happened after the advent of Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane’s music of the early sixties, because at that point for the very first time, there was an influx of artists who couldn’t satisfy the technical qualifications required of them to get on to the bandstand prior to this era. Before this era, if you wanted to play with Miles Davis or Monk or Herbie Nichols or whomever, there were certain things you had to do — as in any fine art — in order to succeed. Hand in glove with the social changes of the sixties, all of a sudden you had people who were being talked about as major jazz figures, who frankly, as Stanley Crouch put it, “couldn’t play the blues in D flat.” That is when I was coming up. That is the jazz world in which I entered in the seventies. It was a very confusing and very marvelous place. To use a cliché, I don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater, some very good music came out of that era, but I really think that was a radical departure for jazz, and I think it’s one that is finally being addressed.

JJM Did the jazz of the “avant-garde” lead consumers away from jazz during this transition?

LS As you well know, you can go back to Plato for quotes about people not understanding music, about music sounding funny and of being redolent of questionable social values. Without a doubt, the “avant-garde” — the jazz of the sixties and seventies that we are talking about — drove a lot of people away. But it is an inevitable cycle of a popular art form where it outgrows its functions just as a kid outgrows adolescence. Many people think that jazz has become something radically different, but I think that is why ultimately Wynton Marsalis becomes such an important figure.

JJM Your book is geared toward introducing new listeners to the history and to the players in jazz. People who are just getting into jazz are likely to have heard of Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, and Charlie Parker. These recognizable names could be called “heroes “of jazz. In your opinion, who is an unsung “hero” of jazz?

LS The trumpeter Frankie Newton is an unsung hero of jazz. Rex Stewart would be another.

JJM Why Frankie Newton?

LS Because he was, to begin with, a supreme artist and individual. Newton was someone who bucked the system at a time in which you really couldn’t buck it, and he got messed up because he told the powers that be — the “jazz producers” of the day — that he really wasn’t interested in any element of playing their game. This worked to his disadvantage. He was pretty much blacklisted from recording during his prime years. You will find very few Frankie Newton recordings after 1938 or 1939. I can’t comment on his political beliefs specifically, but he was politically active, and I know that it got him into a heap of trouble. The reason that I call him a jazz hero is because he was such a great trumpet player, and his playing was infused with such humanity and depth. As a Frankie Newton collector, you wind up scouring every single groove of every record he ever made, just looking for information and pondering it.

JJM As consumption of jazz music continues to fade, how does it remain relevant to the culture?

LS That’s a good question. I think I have a good answer. I teach, and one of the best things about teaching is that I come in contact with many of the best young players who migrate to New York, and I encounter players from other places too. These young players are making jazz relevant. As long as these players are coming up from the background they come from by virtue of when they were born, that is going to keep it relevant, because they are bringing all these things to it. I have encountered phenomenal young players. There is an alto saxophone player named Kris Bauman, and another, Dayna Stephens, both of whom are among the most thrilling improvisers I have ever heard in person. So yes, jazz will remain relevant. Is it ever going to be what it was? No. It may be something better, it may be something worse.

JJM You wrote something about how proud you were while looking out into the audience at Jazz at Lincoln Center and seeing people of all colors participating in jazz, witnessing their appreciation of it. I think that is a pretty good answer, too, in terms of its relevancy. The fact that jazz has an ability beyond just being a musical art form — that is a force that merges cultures is pretty remarkable. In fact, you could probably make the case that when you look out into the faces of a typical jazz audience, you are seeing the improvisation of the human race. Perhaps jazz is more relevant as a cultural connector than as a musical art form.

LS Interesting point

JJM One last question. If you could choose an event in jazz history that you could have attended, what would it be?

LS I have debated about this. I have been talking about this with Dan Morgenstern for almost thirty years. Where to go in a time capsule? Many people say they would like to have been at the record date where Louis Armstrong recorded “West End Blues,” or something like that. First of all, I would love to have been to a place that was not a recording. My own personal obsession that I hope I never get over is the music of Lester Young. I guess if there was one place I could be it would be at the famous jam session in Kansas City in late 1933 with Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young. That is where I would want to go, because, first of all, we don’t know what Lester Young sounded like as a young man. He didn’t make his first record until he was 28, and I would love to have heard him at 20 or 24, to see how he evolved. To hear him play that night, through the night and into the morning, exhausting himself with Coleman Hawkins, is where I would wish to be.

__________________________________________-

The NPR Curious Listener’s Guide to Jazz

by

Loren Schoenberg

_______________________________

Loren Schoenberg products at Amazon.com

Loren Schoenberg’s Web Site

_______________________________

This interview took place on September 9, 2002

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with cultural critic Martha Bayles.

*

_______________________________

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews