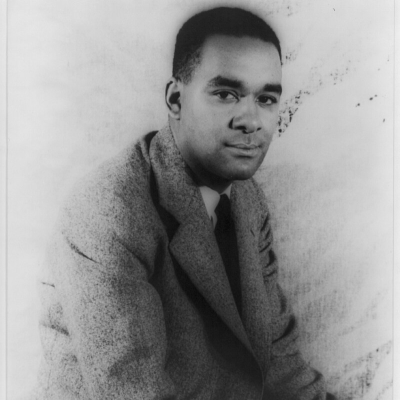

Jerry Zolten,

author of

Great God A’Mighty – The Dixie Hummingbirds:

Celebrating the Rise of Soul Gospel Music

_____________________________

From the Jim Crow world of 1920s Greenville, South Carolina, to Greenwich Village’s Café Society in the ’40s, to their 1974 Grammy-winning collaboration on “Loves Me Like a Rock,” the Dixie Hummingbirds have been one of gospel’s most durable and inspiring groups.

When James Davis and his high-school friends starting singing together in a rural South Carolina church they could not have foreseen the road that was about to unfold before them. They began a ten-year jaunt of “wildcatting,” traveling from town to town, working local radio stations, schools, and churches, struggling to make a name for themselves.

When James Davis and his high-school friends starting singing together in a rural South Carolina church they could not have foreseen the road that was about to unfold before them. They began a ten-year jaunt of “wildcatting,” traveling from town to town, working local radio stations, schools, and churches, struggling to make a name for themselves.

By 1939 the a cappella singers were recording their four-part harmony spirituals on the prestigious Decca label. By 1942 they had moved north to Philadelphia and then New York where, backed by Lester Young’s band, they regularly brought the house down at the city’s first integrated nightclub, Café Society. From there the group rode a wave of popularity that would propel them to nation-wide tours, major record contracts, collaborations with Stevie Wonder and Paul Simon, and a career still vibrant today as they approach their seventy-fifth anniversary.

In Great God A’Mighty – The Dixie Hummingbirds: Celebrating the Rise of Soul Gospel Music, author Jerry Zolten brings vividly to life the growth of a gospel group and of gospel music itself.* He joins Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in a conversation about the Hummingbirds, and on gospel music’s golden age.

______________________

“(The Hummingbirds’ singing) gave us inspiration. Whenever they came around, it was a tremendous uplift that helped us cope and deal with all of the negative things that was going on at the time. Racism, social injustice, economic injustice. The ‘Birds would sing and it would just seem that heaven came open and God had come down. We just felt like we could deal more with what we had to deal with, after hearing them.”

-Pastor Gadson Graham, Canaan Baptist Church, Paterson, New Jersey

_____________________________

JJM Why did you choose to profile the Dixie Hummingbirds and not the Golden Gate Quartet or other gospel groups of that era?

JZ I guess one way to answer that is to say that ultimately the Hummingbirds chose me. I had been working with another gospel group, the Fairfield Four, who had a lengthy career dating back to even before the Hummingbirds began. The Fairfields were from Nashville and were influenced by Birmingham, Alabama gospel, and had been major players within the African American community up until the time of their retirement in 1950. They were retired for over thirty years when I ran into them in the early eighties. I fell in love with how they sounded and tried to get them back into touring and recording, which they did, ultimately recording for Warner Brothers.

During this same time I had been trying to track down the Dixie Hummingbirds because I wanted to present them at various festivals and venues I was involved in. Eventually, our paths crossed and they became aware of my work with the Fairfield Four and wanted some of that to happen for themselves, and it was in this context that Ira Tucker of the Hummingbirds asked me if I would consider writing a book about them. I had actually been contemplating writing a book about the Fairfield Four, but the thing that made the Dixie Hummingbirds appeal to me was that they came with ready-built name recognition which was what I needed in order to interest a publisher. Also, I knew that their career encompassed much of the history of twentieth century gospel, and that they were one of the top groups in the genre. They touched more bases in and out of the gospel genre than any other group I could think of. Since I wanted to tell a deep gospel story and at the same time throw a spotlight on some of the under-appreciated heroes of the genre, centering the book on the Dixie Hummingbirds seemed like the right thing to do.

JJM James Davis was the founder of the Hummingbirds. What was his musical foundation?

JZ He grew up in the Meadow Bottoms area of Greenville, South Carolina, during the time of Jim Crow, and in a family that was totally involved in the church — in his case the Church of God Holiness. The area was called Meadow Bottoms — which was actually Meadow Street — because it was flooded out and the houses were built up on stilts to keep them from getting flooded. The church was right there in the neighborhood.

His father was an itinerant who would leave for long periods of time, but when he was around he steeped himself in music.. Music was the one thing that James Davis’ father took seriously. He began training young James in the art of singing as soon as he was old enough to make sense of it. The method he taught was shape note singing. If you look at a shape on a piece of paper, a triangle might be “doe”, a square might be “mi”, a circle might be “ray,” and you learn to associate a note with a shape, and that is how James learned to sing.

He was aware of other kinds of music in Greenville. While it wasn’t a huge town, they did have a venue where some out of town bands with a reputation would come through. For example, Davis distinctly remembers when Cab Calloway came to town. . He would be aware of performers like Calloway, and he would know their music through the radio, but he wouldn’t necessarily go to see a show. He saw many street performers — gospel singers, blues singers — and, of course, he constantly heard choirs and quartets in church, and you could say that those experiences were his musical roots. By the time he was ten or eleven years old, he was singing in a gospel group.

JJM The church shaped him in so many ways, and it certainly shaped his values as a performer. What were the “Davis Rules”?

JZ James Davis was famous for his rules, not just within the Dixie Hummingbirds, but celebrated amongst all their fellow travelers on the gospel highway. Everybody knew that Davis ruled the group with a legendary iron hand. By and large the rules were pretty practical, and were based in experiences he had early on. His number one rule was “absolutely no drinking of any kind at any time or any place,” which was rooted in one of his earliest experiences. When he was still a kid, he and some of his friends got a little gig singing at a church some distance from home, and one of the boys found some liquor and got tipsy on it. Word got back to his mother and she made him break up that group and James never forgot that. Even later, as he was trying to get the Hummingbirds into professional shape, he had singers who turned out to be drinkers who he couldn’t rely on. So, because he wanted to be professional, no drinking was his number one rule.

Another rule was that no women could be in the car at any time. There was an incident when Jimmy Bryant, the ‘Birds popular bass singer, had a lightly complected girlfriend, and the word spread that an angry mob was going to run the group out of town. People thought he was flirting with a white woman. The ‘Birds had to slip away before there was any trouble and Mr. Davis took firm cautions from then on. Another dimension to his rules was his fundamental belief that the ‘Birds had an obligation to live the life they sang about, and that if you weren’t an exemplar in the world of gospel, you wouldn’t be taken seriously. In time, the rules would cover everything from public image to sheer business acumen; for example, administering fines if you were late for rehearsal, no curse words could be used at any time in any place. No listening to blues music was allowed, and group members were not allowed to play anything other than gospel music in the juke box. These rules had to do with living the life they sang about and some had to do with maintaining a high standard of professionalism.

JJM You claimed Jimmy Bryant of the ‘Birds to be a sort of Dennis Rodman of gospel.

JZ Yes, there is an illusion that one has of gospel singers as being “holier than thou,” but, like anyone else, some of them were quite flamboyant. Bryant, their star bass singer, really couldn’t sing bass all that well, but he was good looking, knew how to work the crowd, and, as the guys would say, he knew how to “sell it.” He had a persona that communicated to others that he knew what he was doing and was right where he belonged. He would lean over backwards, jump, gesture, and do whatever it took to get the crowd’s attention. He was a colorful showman and that is what prompted Mr. Davis to compare him to Dennis Rodman.

JJM Zora Neale Hurston wrote that spirituals were “variations on a theme, bent on expression of feelings. The congregation is bound by no rules. No two times singing is alike, so that we must consider the rendition of a song not as a final thing, but as a mood. It won’t be the same thing next Sunday.” What was the source material for spirituals?

JZ That is an interesting question because those sources are part known, part unknown. The knowable sources are the Anglo hymns, the songs like those of Dr. Watts that the masters taught the slaves in their earliest days on American soil. The hope was to teach them English, provide a spiritual bond in a kind of twisted vision of Christianity where the “meek”– read “slaves”– shall inherit the earth. The unknown would be the African songs and styles and ideas that slaves brought here with them. Over time, the African would reshape the Anglo and out of it all arose the spirituals, the first tradition of black religious singing, and, as with any oral culture, it is impossible to know who wrote them. Songs like “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” and “Roll Jordan Roll” and “Go Down Moses.”

One element that I could not capture in my research is what those songs might have sounded like as they were sung in the southern congregations Zora Neale Hurston describes, where people are just making it up as they go. This was happening in little churches all throughout the South. The spirituals would get passed along from generation to generation. They were not written down — they were truly an oral tradition.

When the Hummingbirds first started performing, they simply picked songs that they had already learned. Of course, by the time they began singing, the tradition was no longer strictly oral and lyrics could be found written down. But the Birds did not learn that way. They didn’t go to books and read what musicologists may have notated about particular songs, they simply took songs they had heard and reworked them out loud. The ‘Birds would take songs such as those Hurston describes, that had no arrangements — only lyrics, a melody and perhaps a rag tag harmony — and they would create some order to them. They would work them out for four or five voices, and work them out in their heads, never singing them the same way twice.

JJM You quote Lionel Hampton as saying, “I started working on my musicians to play with that kind of inspiration. And I think I was the first to bring all that music from the Holiness church — the beat, the hand clapping, the shouting — out into the band business.” You wrote that gospel, unlike jazz and blues, remained “culturally confined.” What was borrowed from gospel by popular musicians of Hampton’s era?

JZ For one, the importance of improvisation to performance. I believe that blues and jazz performers all draw from the well of religious music, which demands a certain improvisatory quality. It also exposes the artist emotionally, where he is not worrying so much about getting the note right as he is getting it emotionally ready to perform, so the audience feels something. From that a certain honesty is demanded and communicated.

A good piece of music is designed to transport you to some other place. I think the great jazz and blues musicians may have first felt this when listening to and in many cases actually performing religious music, and then took it into mainstream music — perhaps never quite with the vigor or totality of a religious performance, but with many of those earmarks. I don’t think Lionel Hampton was the first, but he certainly was one who drew on those traditions.

JJM Were groups like the Hummingbirds successful in bringing an understanding of black culture to a white audience?

JZ I don’t know that the ‘Birds did that in their earliest days. They made their first record in 1939, and it isn’t likely that many people beyond those in the African American community bought it. As the forties unfolded, however, gospel groups were occasionally breaking through to the white mainstream, but never in the way people like Hampton, Charlie Christian, Fletcher Henderson or, ultimately, Duke Ellington did.

JJM You wrote, “Gospel music was one of the few occupations for people of color that offered them a measure of dignity and promise.”

JZ Yes, there weren’t many options. James Davis and Ira Tucker both expressed that they didn’t want to be stuck in South Carolina doing “drudge work.” They felt that was their fate if they remained. Davis joked with me about how the only things a black person could do to break out was to be either a boxer or an entertainer. While being an entertainer was a way out, being a jazz or blues musician would bring down the wrath of the religious black community upon you. So, if you sang spirituals, that would get you blessings from everybody, except you would never achieve mainstream success. That would change a little with a group like the Golden Gates, who were the best example of a gospel group who managed to break through, although they never made the financial gains that groups who sang secular music would — the Mills Brothers and the Ink Spots, for example.

JJM What were the circumstances that led to the Hummingbirds’ move from South Carolina to Philadelphia?

JZ They had pretty much saturated the South Carolina region, which relative to the Northeast, for example, is a very rural part of the country. By 1941 they had played every church a hundred times over, and they were finding that if they wanted to keep working as professionals, they would have to travel further and further away. By then they had families growing, and it was getting to be really very frustrating for them to be away so much. They were hoping to establish themselves in a heavily populated place so they would not have to travel so far and wide.

As it turned out, an old friend of theirs from Florida, Charlie Newsome, was managing a group called the Royal Harmony Singers. Through efforts, the Royals got a gig at WCAU radio in Philadelphia. However, the group fell apart before the show got off the ground, and Newsome contacted the only other group he knew well, the Hummingbirds, and asked if they wanted the gig. One of the guys in the ‘Birds, Barnie Parks, had a little family in Philadelphia, and the city was right on that corridor from New York to Washington and Baltimore. It was just what the ‘Birds were looking for, so they decided to make the trip. They also hoped that by moving north they would escape the prejudice in the South, although it turned out there was plenty of that there as well, it was just packaged a little differently. Nonetheless, they had no regrets, and that is how they came to Philadelphia.

JJM They had some success getting on the radio, performing on the radio station right away.

JZ Yes, they were doing one, two or three songs, bright and early every morning. It was the sort of work available to African American gospel groups at the time.

JJM In 1939, John Hammond put together an event in Carnegie Hall in 1939 called “From Spirituals to Swing.”

JZ Yes. His idea was to capture the whole sweep of black music, from spirituals to swing. He felt that, at the time, African American musicians across all genres had never received their due, and that the mainstream public didn’t really know their names or their work. There were not enough opportunities for people to frequently see them. Consequently, these musicians didn’t make the sort of money they deserved. Prejudice was a roadblock to their playing in the best venues and to their having quality recording contracts.

Hammond, partially to rectify some of these inequities and partially because he loved the music, staged this event at the classiest venue he could think of, Carnegie Hall in New York City. His goal was to provide the performers with a place to perform with dignity and create an opportunity for music fans to see the best in black music, close up in a fine concert hall.

The performers on the bill included everybody — Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Charlie Christian, Benny Goodman, the Golden Gates, and a relatively primitive gospel group from the Carolinas called The Mitchell’s Christian Singers. The concert was also famous because the great blues musician Robert Johnson was invited to perform, which would have been the first time he had ever traveled out of Mississippi to appear in concert. However, as they soon discovered, he was already dead. His name actually appeared on the program.

JJM Right around that time, Barney Josephson opened Café Society and hired Hammond as musical director.

JZ That’s correct. Josephson didn’t know all that much about music, but he was a political activist who wanted to shake things up and make a dent in segregation. At the same time, it gave him a chance to get involved in what he thought to be an exciting musical enterprise. But he didn’t know the musicians well enough to choose the best talent for the club, so he came to John Hammond for that.

JJM Given their background and audience, how did the Hummingbirds fit into this night club scene?

JZ It was a somewhat totally new situation for them. I say “somewhat” because they had performed for white audiences before, but there were a couple things going on here that were new. One was that they now had instrumental backing — it was one of their first experiences with that. They sang “a cappella” up until this time. While they still performed “a cappella” in their set, they also did numbers backed by the great saxophonist Lester Young, who had a band with his brother Lee at that time. Lester’s band wasn’t there for the entire duration of the ‘Birds stay at Café Society, but he was there for a good bit of it, and I know Ira Tucker, for one, really enjoyed the camaraderie.

As an aside, when I sit with the ‘Birds and talk about music, they love to talk about jazz and bop and the sounds of Basie and other jazz greats. They have always been fans of the music even though they didn’t perform it.

At Café Society, they were working a sophisticated club, and they enjoyed wearing very elegant clothing. They had to work on every nuance of their act. In essence, they were a foil to the Golden Gates. When the Gates were playing Café Society uptown, the ‘Birds would play at the Café Society downtown, and sometimes vice versa. When the Gates were out of town, the ‘Birds were the resident gospel group. They weren’t called the Dixie Hummingbirds during their time there. Josephson called them the Jericho Quartet or Quintet, depending on how many were in the lineup on a given night.

JJM Why did Josephson insist on changing their group name?

JZ We don’t know for sure. It wasn’t the Hummingbirds’ choice, it was Josephson and Hammond who decided they should be called the Jericho Quartet. Ira Tucker thought it was because the term “dixie” had too many associations with racism, and that Hammond and Josephson may not have liked the name “Hummingbirds.” It’s possible they thought that Jericho was a little more neutral, but I have never been able to really establish that. I actually did an interview with John Hammond once, but this was never discussed. Had I known I was going to be writing this book at that time, I would have asked him.

JJM During their career they were under some pressure from their record company, Apollo Records, to cross over into secular music. Did that ultimately lead them to move to another record company?

JZ After they left Café Society, they went back out on the road and realized things were changing rapidly, that records — especially gospel recordings — were the up and coming thing. Back before the war, they had, of course, made some records and the Golden Gates and a few other groups had already been making records steadily, but now post-war, there was a growing market for records by African American artists for African American consumers.. Breaking back into the recording business did not at first go smoothly for the ‘Birds. They did quite a few recordings with small labels starting in 1944, the most successful being on a Philadelphia-based imprint, Gotham. Why “Gotham” in Philadelphia? Because the label had been started by Sam Goody in New York City, but he sold it to Ivin Ballen of Philadelphia, and that’s who the ‘Birds recorded for in those days. But it wasn’t until 1946 that the ‘Birds moved up a notch and began recording for the Apollo label, which was three years after their run at Café Society.

JJM Apollo was having some success with secular music.

JZ Yes, they sure were.

JJM There was some hope among those at Apollo that the ‘Birds would go beyond gospel recordings and into secular music.

JZ It didn’t happen immediately, but yes, Apollo was recording jazz, jump blues and vocal group music, and the market for those genres was very hot. Young African Americans were returning home from the war with money in their pockets. The market was so hot that you could literally have a million-selling record. But, while there were some gospel recordings that sold well, they never sold anything like a secular hit would. Label owners consequently tried to get double duty out of their groups, asking them to record something under another name for the secular market, which would allow them to cash in twice. There was a group on Apollo who did that, the Larks, also known as the Selahs. They recorded gospel as the Selahs and they recorded jump blues, vocal group music as the Larks. Whether the record buyers knew they were hearing the same group or not, I don’t know. It was indeed an interesting time.

JJM Peacock Records founder Don Robey was a notorious thug who got into fights with his artists and threatened them with weapons if they asked out of contracts. In fact, the way he ran his label sounds more like a modern day rap label than that of a gospel impresario. Given the character of the ‘Birds, how did they deal with Robey?

JZ Gospel wasn’t Robey’s primary thing. It turned out to be, but gospel isn’t how he started. I do give a little background of his underworld connections in the book, and he certainly wasn’t alone in this. There is the legendary story, for instance, about singer Jackie Wilson being hung out of a hotel room window by his feet until he stopped complaining about his royalties — or lack thereof. While Robey’s character and behavior was notorious, the ‘Birds got along with him fine. None of them ever complained to me about him or felt they were mistreated. He never got rough with them, according to the ‘Birds, but they did assume he was keeping more profits for himself than he admitted to. That was just a fact of life, as far as the ‘Birds were concerned. Overall they were very happy with their relationship with Peacock and Robey.

JJM Clara Ward said of gospel, “I think it fills a vacuum in people’s lives. For people who work hard and make little money it offers a promise that things will be better in the life to come. It’s like in slavery times, it cheers the downtrodden.” How was gospel music marketed during the 1950’s?

JZ What she didn’t mention was that this was primarily a black audience. I don’t know that it was that way within white America, although I am sure there were people listening to it. By the fifties, you began to see rather large ads in Billboard magazine mixed right in with the rhythm and blues and jazz. It was not unusual to see a big ad from a particular label for a rhythm and blues group, and right next to it a gospel group is advertised. Robey made use of that medium quite a bit. Of course, Billboard ads were directed at record store owners and radio stations rather than at consumers, specifically. In support of the ads, Robey and promoters working for him would travel across the country and visit the radio stations, which by this time was the way the public was hearing the music. Also, African American newspapers like the Chicago Defender or Pittsburgh Courier occasionally advertised long lists of the latest spiritual tunes available, which consumers would have the option to buy through the mail.

In earlier times, for instance, when they were recording for Regis Manor Records in the forties, part of the Hummingbirds’ pay was in records they could sell at their performance. That served the purpose of providing some extra income for the group as well as being an arm in the distribution of the record. By the time they recorded for Peacock, they didn’t necessarily travel with a lot of records. Robey really had distribution covered between radio play, mail order, and the record stores.

JJM What were the physical aspects of the Hummingbirds’ stage show?

JZ During the years of their quintessential line-up — Ira Tucker, James Walker, James Davis, Beachey Thompson, William Bobo, and Howard Carroll — roughly throughout the fifties and sixties, they always dressed immaculately. They postured and they pointed, they fell down on their knees, “holy walked” out into the crowd, reached out and touched people, screamed and shouted, sang it slowly and in sweet harmony. You name it, the ‘Birds did what it took to set the crowds on fire.

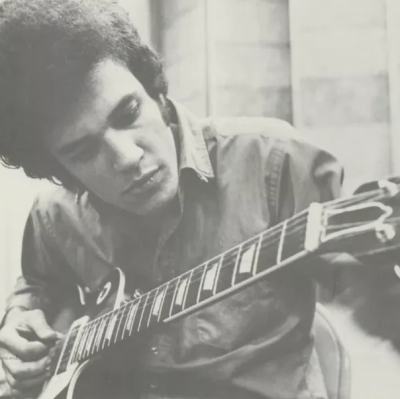

JJM How did the addition of electric guitarist Howard Carroll affect the way the ‘Birds sang?

JZ Howard’s move into the group took some adjusting. They had had some experience with instrumental backing — drums, organ, that sort of thing, and, of course, Lester Young’s small band — but with the guitar, they had to find their space, Howard his. He ultimately was the one who had to fit his style in and behind the ‘Birds, and he was masterful at it. He developed a style that supported and accented, a combination of bass runs played in between chords and little lead flurries when space provided between the vocals.

JJM What influence did the ‘Birds have on the next generation of singers? What gospel singing techniques were absorbed by secular music of R&B and soul?

JZ The ‘Birds impacted their secular counterparts in so many ways. James Davis likes to tell how they were always about a decade ahead of the curve. Back in the forties, the ‘Birds were performing the a cappella harmonies that would inform the doo wop and jump blues of the fifties. But when that music was in its prime in the fifties, the ‘Birds had already moved on to the electric guitar soul sound that would influence the sixties. Otis Williams of the Temptations says that his group actually took schooling from the ‘Birds on everything from harmonizing to stage moves. They were especially fond of bass singer William Bobo. Hank Ballard and Jackie Wilson borrowed freely from the ‘Birds’ songbook. As the late Hank Ballard told me, he’d call the ‘Birds on the phone and ask permission to borrow a melody or a bit of lyric.

JJM What impact did gospel music have on John Coltrane?

JZ A friend of mine, Steve Rowland, put together a radio documentary on Coltrane and from it I learned a lot. Among others, Coltrane listened to the black gospel preachers on radio when he came to Philly in the forties. He would build compositions on their cadences and flow. I guess one of his most famous pieces, “Alabama,” was based on the feel of Martin Luther King Jr’s eulogy to the four children killed in the Birmingham church bombing back in the sixties. I think music and religion were synonymous to Coltrane. Music was his religion, and that’s pretty profound, I think.

JJM Did the Dixie Hummingbirds’ music become political as a result of the events of 1963?

JZ By 1963, their two primary songwriters were James Walker and Ira Tucker, both of whom had already written material that had a kind of social commentary to it. During the fifties, Walker wrote a tune that he recorded with another group on the Trumpet label out of Jackson, Mississippi called “Our Prayer for Peace,” a song whose message is that we are all brothers regardless of skin color. So, Walker had already written songs with a somewhat political theme before 1963. In fact, I was very struck by how similar at times “Our Prayer for Peace” is to John Lennon’s “Imagine.” Who knows if Lennon ever listened to it, but it is very interesting how similar the lines were.

Tucker had always been taken with Paul Robeson, who he met in the forties at Café Society. Robeson pioneered the art of writing or interpreting material that spoke out about social injustice, racism and that sort of thing. Robeson wasn’t the only one. Billie Holiday sang “Strange Fruit,” and blues singers Leadbelly and Big Bill Broonzy as well wrote politically conscious material in the forties. The very first record the ‘Birds cut for Peacock in 1952 was a Tucker song called “Wading Through Blood and Water,” which was an anti-war song about Korea.

While performing politically conscious material wasn’t new to them, the events of 1963 certainly brought that out more. For instance, the group had been performing Walker’s “Our Prayer for Peace,” but they wrote a special verse for it about the assassination of President Kennedy. Later, they would also add a verse about Martin Luther King, Jr. In a general way, songs they wrote and performed were meant to be food for thought and for people engaged in the civil rights movement. Much of their music had that kind of double focus.

JJM How did Martin Luther King’s death affect how black and white soul musicians worked together?

JZ The question brings to mind the ironies of the sixties soul era, the idea, for example, that Motown relied primarily on black musicians to create a smooth, polished sound that appealed to white teens, while labels like Stax and Fame, where the music was much grittier, relied on white instrumentalists to get that “authentic” soul sound. That always intrigued me. But, to answer your question, I once saw a documentary, I think it was the PBS series on rock ‘n’ roll, where musicians who worked for Stax Records — people like Steve Cropper and Donald “Duck” Dunn — discussed quite poignantly about how after King’s death the connection among white and black musicians fell apart. At Fame Studios, for example, the people there claimed that black artists just stopped coming. Nobody ever said anything flat out, but it just stopped.

JJM How did Paul Simon choose the Hummingbirds to sing with him?

JZ The ‘Birds weren’t his first choice. It was actually Claude Jeter and the Swan Silvertones he was initially interested in. Simon actually borrowed the line “bridge over troubled water” from Jeter’s performance of “Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep.” He became friendly with Anthony Heilbut, author of one of the most important books on gospel music called The Gospel Sound, and who at the time was a producer for the Newport Folk and Jazz Festival. In that particular year, 1972, the Newport Jazz Festival took place in New York City, and the ‘Birds performed at an indoor auditorium which Simon witnessed from backstage with Heilbut. Upon hearing them, Simon thought that they could be the group to work with on the album he was working on. I can’t tell you exactly what was going on in his head and why he went with that choice, but that is how it came to be.

JJM Did the ‘Birds ever regret their decision to sing with Paul Simon?

JZ No, they never did. If it weren’t for that association, their name wouldn’t be nearly as well known as it is today. They have no regrets about that. At the time, they had to deal with some backlash within their own community. I have always found it interesting that at the time one of their critics of their work with Simon was Thermon Ruth, who ran the gospel shows at the Apollo Theatre. Ruth was one of the first promoters to bring gospel to the Apollo, and he did it for years. He was critical of the ‘Birds, among others, for crossing over and getting into the “devil’s music.” This is quite ironic, because it was Ruth’s Selah Singers who also performed as the Larks for Apollo, so it is hard to understand why he would criticize the ‘Birds for working with Simon. So, the Hummingbirds certainly may have lost some of their core fan group, but at the same time they gained an audience that was larger than they ever imagined.

JJM The Hummingbirds’ commitment to their audience may have cost them some money.

JZ Yes, they could have made a lot of money touring with Simon but turned him down because they had commitments to perform at a string of little churches. They weren’t going to make nearly as much money, but they had commitments and they didn’t want to abandon their core audience. That is one of the things that made the Dixie Hummingbirds so highly regarded within the gospel community.

JJM What was the apex of their career?

JZ I don’t know if there was any one apex. Many would point to “Loves Me Like a Rock,” which opened them up to their largest audience ever, but there are numerous other moments — like in the forties at Café Society, or when they appeared with Sister Rosetta Tharp on major gospel shows with thousands of people in attendance. There are so many interesting little peaks.

Their greatest success as gospel singers came with Peacock. Their recordings of tunes like “Christian’s Automobile” and “Let’s Go Out to the Programs” were the musical peaks of their “purist” career.

The Inner Man

It’s the Inner Man,

What’s in a man,

That counts.

It’s not his height,

Not his size,

Not the color of his eyes.

It’s the inner man,

What’s in a man,

That counts.

– James Davis

_____________________________

Great God A’Mighty – The Dixie Hummingbirds:

Celebrating the Rise of Soul Gospel Music

by

Jerry Zolten

*

About Jerry Zolten

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

JZ Probably any number of black rock and rollers who were coming up at the time. I related to rhythm and blues musicians more than anyone else, and it is hard to name only one because I loved them all.

I grew up in Pittsburgh in the mid-fifties and early sixties, and was listening to black radio. There was one disc jockey in particular, Porky Chedwick, who I admired because he played music by people who were my heroes. He never told us who the musicians that he played were, he just played the records, which of course added an even greater mystery to the music. He played a lot of doo-wop, New Orleans and jump blues. While I didn’t always know who I was listening to, I just knew I loved it.

Jerry Zolten with the ‘Birds and the Fairfield Four, 1991

________________________________

Dixie Hummingbirds products at Amazon.com

Jerry Zolten products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

Interview took place on March 10, 2003

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Billie Holiday historian Farah Griffin

*

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews

* From the publisher

photos used by permission of the author