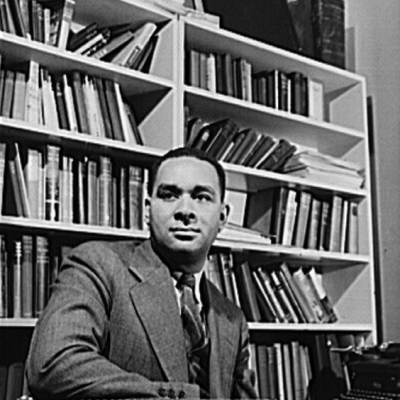

The question of what constitutes art and where lies the cutting-edge of artistic expression has occupied critics for generations. Here, the noted art critic Clement Greenberg, famous for his unflagging promotion of abstract expressionism, studies a Kenneth Noland painting.

___________________________

The fact that writer Stanley Crouch is willing to speak his mind has been known to readers of cultural criticism for three decades. Depending on one’s outlook, his views on jazz, politics, and race often spark outrage, applause, or provoke debate.

In April, 2003, Jazz Times magazine, host to Crouch’s monthly column “Jazz Alone,” published “Putting the White Man in Charge,” a provocative essay covering topics familiar to Crouch readers, most notably his aggressive defense of the jazz idiom and its African American heritage. In the essay he wrote that critics like respected Atlantic Monthly writer Francis Davis see “jazz that is based on swing and blues as the enemy and, therefore, lifts up someone like, say, Dave Douglas as an antidote to too much authority from the dark side of the tracks.”

As a result of “White Man” and the subsequent May essay on pianist Eric Reed, “Piano Prodigy,” Jazz Times dismissed Crouch via email, telling him that the column had “run its course.” This was viewed as a curious move to Crouch and others, since only a month earlier this column which had “run its course” had been billed by the magazine as his most “incendiary” yet. Soon after his dismissal, Crouch contacted journalists, including Jerry Jazz Musician, seeking a wider discussion of the event. In Crouch’s view, more is at stake than his sacking, writing, “At the center of the issue is whether or not there is room for a voice that disagrees with the jazz critical establishment.”

It seems like a legitimate question. Is there?

We decided that a conversation among Crouch and two other prominent critics within the jazz community would be the most viable approach. We settled on the highly respected cultural critic Martha Bayles, author of Hole in Our Soul: The Loss of Beauty and Meaning in American Popular Music, and musician Loren Schoenberg, who, among other duties serves on the faculty at Julliard, is executive director of the Jazz Museum of Harlem, and author of The NPR Curious Listener’s Guide to Jazz. All three of the participants had previously been interviewed in the pages of Jerry Jazz Musician.

While Crouch’s dismissal was the initial focus, the conversation then turned to the subject of jazz criticism and the divide, in Crouch’s view, between critics who favor the expansion of jazz beyond its African American heritage — including the introduction of European classical elements — and those like Crouch, who define the idiom more narrowly, preferring the music of Wynton Marsalis and the musicians associated with Jazz at Lincoln Center.

The edited transcript of the lengthy conversation reveals a discourse rarely printed in jazz journals, and once again demonstrates how publishing on the Internet may provide readers of a particular genre with the most extensive and rewarding experience.

At one point during the conversation, when describing the mindset of critics who consider themselves to be the leading edge of artistic change, Bayles brought up the critic Clement Greenberg, who championed abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Kenneth Noland and who, according to Bayles, “believed in cutting-edge arts that would push the world toward a socialist future,” and in artists who were “the leading cutting-edge not only of artistic change, but by implication of social and political change.” His support of and belief in these expressionists eventually became popular opinion.

It was at Crouch’s suggestion, then, that this May 4, 2003 discussion be titled “Blues for Clement Greenberg.”

Roundtable hosted by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita.

*

Roundtable Participants

Martha Bayles

Cultural historian and critic, Honors Program professor at Boston College, author of Hole in Our Soul: The Loss of Beauty and Meaning in American Popular Music

_____

Stanley Crouch

Cultural critic, New York Daily News columnist, former Jazz Times columnist, author of Reconsidering the Souls of Black Folks, The All American Skin Game, Notes of a Hanging Judge, Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome

_____

Loren Schoenberg

Conductor, saxophonist, recording artist, faculty at Juilliard, Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Essentially Ellington Band Director’s Academy, Academic Director Jazz Aspen Snowmass Academy, Executive Director of The Jazz Museum In Harlem, author of The NPR Curious Listener’s Guide to Jazz

___________________________

JJM The impetus for this panel came as a result of Stanley writing me an email, informing me that his Jazz Times gig as columnist was terminated. He wrote, “At the center of the issue is whether or not there is room for a voice that disagrees with the jazz critical establishment.” Let’s start there. Is there room for such a voice?

MB I have a question. Where do I locate the jazz critical establishment? I don’t really have a sense of what amounts to the “establishment” these days.

LS One of the problems is that there is no forum for any serious debate about issues in the jazz community, and that may be one of the reasons you (Martha) have trouble finding it. All that ever really appears are a couple of regular editorials in a handful of publications, and the occasional article in a major newspaper or magazine. But, it is like a one-sided tennis game. Nobody ever “bats the ball back” because there is a kind of unanimity among whomever the major writers are considered to be. Perhaps the greatest import of the action Jazz Times took in firing Stanley is that they basically told their readers that the jazz community can’t take someone with a strong opinion opposed to those of the major writers, and that they don’t have the respect for the jazz public and for their readers.

MB I feel somewhat at a disadvantage because I don’t read Jazz Times, so I don’t have a sense of what they tend to communicate. Maybe you could enlighten me, Stanley. Give me some examples of what the drift is.

SC You saw my piece, “Putting the White Man in Charge”?

MB Yes.

SC It is laid out in the piece. In other words, the argument that the writer Tom Piazza makes about that particular vision that these critics have, in which he writes “Many jazz reviewers – especially among the generation that grew up in the 1960s and ’70s – suffer from intense inferiority feelings in front of the musicians they write about. This results in a vacillation between an exaggerated hero-worship of musicians and an exaggerated sense of betrayal when the musicians don’t meet their needs.” This is his observation as a man who moved among critics and it is his interpretation of how they think and what they are like. Then there is the argument in the piece where I write that a musician like Dave Douglas has been elevated beyond his abilities in order to substantiate a certain kind of ideology that seems to be the dominant way of looking at things among those critics.

MB Well, I am getting two things off of this. One is that, in all the arts, there is a general bias in the critical community toward what is considered cutting-edge, innovative, and “out there.” So, there is a tendency to be biased, if you will, toward looking at the “new thing,” to use an old phrase. Consequently, there is a tendency among musicians to go for whatever is passing as avant-garde this week. But, I don’t quite see how that correlates with race, because there are avant-garde black musicians and avant-garde white musicians. There are people of all colors who like and don’t like avant-garde music. Because of this, I am having trouble putting the race frame on top of the styles of music frame. That is really my difficulty with this whole topic.

SC But, you see, if you look at these things like the polls that are put together by the jazz journalists, and look at the people they select, as I say in the piece part of it is racial, but the ultimate thing is an attempt to remove the significance of Afro-American elements of jazz from the discussion. There are all these pieces written by people like Stuart Nicholson and others who write that nothing new is coming out of America, that whatever is new in jazz is coming out of Europe. Throughout the history of jazz there has been this tendency to perceive jazz advancing itself, if you will, by embracing whatever is considered advanced in European music. Dave Douglas, to me, is symbolic of what these guys are after.

JJM Does the disconnect from the African-American tradition make it any less jazz?

SC Yes, it does. In a number of pieces I wrote for Jazz Times, I would say that there are all kinds of music in which people improvise, and from all over the world. What has happened in the arena of jazz writing is that there is no definition of jazz at this point. Jazz is just something that is “improvised,” so the key elements that connect, for example, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane to Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet, are no longer obtained as far as what you get in these jazz magazines. And their whole idea is of how jazz should be “inclusive,” that it shouldn’t “exclude” anything. If that is the case, who is to say what jazz is?

LS I would throw in, in terms of what is driving this discussion, is Stanley’s being let go from writing this column for Jazz Times magazine, and what was really behind it and what the issue really is. I think that a lot of it had to do with the fact that, while Stanley was willing to give Dave Douglas benefit for whatever talents, in his estimation, he has, a lot of the critical community that is behind pushing someone like Dave Douglas has a very dismissive attitude towards Wynton Marsalis and a lot of the folks at Jazz at Lincoln Center. There are so many conflicts and perceived conflicts of interest here that muddy the water. With all the columns and record reviews of varying literary and critical quality that appear in Jazz Times and other jazz publications, it seems to me for Jazz Times to take this action and take away a column from one strong, opinionated voice in the wilderness, in my opinion, is related to his connection to Marsalis. Many other critics have had strong connections to artists that they champion. I feel it is related still to the fact there are perceptions that when Wynton took over at Jazz at Lincoln Center, it was the first time that a major cultural institution had jazz bookings and jazz programs, and it was led by an administration that was less willing to pay obeisance to the white community that dominated and decided who played where and who did what. I can tell you that this reverberated deeply, and I think that some of those reverberations actually are what are bouncing back and led to Stanley being taken out of that magazine. I really do believe that.

MB When you talk about the white community, you mean the kind of gate keeper, decision makers?

LS Yes, the people who ran the record companies, the people who ran the bookings, the festivals, the musicians and all the great “critical heads of jazz.” It would be disingenuous to say that that was not related to this. I see them as related.

MB Can I play the devil’s advocate for the moment, though?

LS Please do.

MB It strikes me that if Stanley’s column was strictly about musical values, it wouldn’t have irritated people quite so much. But when you get into telling white guys that they are uncomfortable being around black guys, that seems like it was sort of calculated to stimulate a reaction

LS Stanley? A provocateur?

MB I hope you will forgive me, Stanley, but I am coming into the tail end of this and I don’t know the degree to which you have been provoked, although I have some sense of that. I haven’t been on the moon all this time. But, what you wrote seems guaranteed to get a huge rise out of people that has nothing to do with music.

LS But, part of my problem, Martha, and I have read your book and I know how much you know, so I have a sense for how you feel about this. It is very much like the elephant in the movie Jumbo with Jimmy Durante, and with the elephant right before him he says, “What elephant?” The fact is that you won’t see any serious reflection on any of these issues that Stanley is raising in his columns. Now, whether or not you or I would express our opinions in the way he did is not the point I am making. The point I am making is at least he is raising the issues. This played out almost as if Jazz Times wanted to have Stanley stir up the community and get a rise of them, and when, in their view, Stanley went too far, they could tell him, “That’s enough.” I am not saying that was an implicit understanding, because it wasn’t as far as I know. But, once Stanley’s work veered towards the critical community, and the magazine felt as if he were savaging “one of their own,” they had enough of the controversy and yanked him.

MB So, Stanley, the substance of your gripe with the establishment and with jazz critics let me see if I can articulate it and you tell me where I am off, OK?

SC It is in the essay. The essay takes a very simple position that there has always been a race problem in jazz and there have always been times when white guys have been given visions of value that exceed what they actually do. It goes all the way back to the beginnings of jazz with Paul Whiteman marketed as the “King of Jazz,” which, as I say in the column, I believe was one of the reasons that led to Duke Ellington’s attempt to get the people of his period to call their music “Negro Music,” and not “jazz.” I think he was aware of the fact that, by that time, in the mid to late twenties, even the white man wasn’t ready to have a white king of “Negro music.” I think that that was very clear to him. White musicians being given more attention in the jazz magazines has been an ongoing issue for a long time. Once upon a time during the thirties or forties there was a big controversy about putting a black musician on the cover of Down Beat. Then there was another thing, when during the sixties a number of black musicians who could not really play but who asserted their own importance based upon some kind of genealogical connection to Africa and Africans, and that the white man had to put up with that in jazz the same way white people had to put up with black power, black studies, and hostility from black kids on campus during the sixties.

So we are now at a point in which this group of guys who define themselves, as I said in the essay, in those terms that Rimbaud described as having a love of sacrilege — that is to say that their position in life is based on their rebellion against something. Now they are at the point where they can rebel against the Negro and the Negro elements in jazz, and are trying to foist people like Dave Douglas on to the scene as though he is the greatest trumpet player out there. There is no real argument about whether he is or is not. The basic thing to me is this. What you see in these magazines is that they decide who the person at the top is. In Down Beat forty years ago, everybody didn’t just go for Ornette Coleman or Cecil Taylor or whomever it was. Now, the situation is that if Dave Douglas is supposed to be numero uno, everybody submits to that. If Wynton Marsalis is supposed to be neo-bop or something, everybody says that. There is not a situation where you have any real debate over the relative merits of different musicians, or what their aesthetic is or is not. That kind of exchange is not going on, and when I got this email pink slip from Chris Porter at Jazz Times, the whole thing took place in an exceedingly unprofessional manner. That is to say, I write about 100 columns a year for the Daily News for six or so years. I have written 600 or 700 columns for them now. My experience is that when you write a column your editor may find to be repetitious or whatever, you and the editor talk that out.

MB I read the message they sent you and it seemed extremely cursory, shall we say…

SC What I am saying is this issue was not handled in a professional manner. He didn’t like a column I sent him. If they were having problems with the column, I am supposed to be the first one to know, and we are supposed to talk it through, which is what people in the professional world do. Due to the fact that nothing like that took place

MB They raised none of these questions when editing the piece?

SC No. I sent one in, and if they didn’t like the next one that came in, they could have sent an email suggesting that we talk more about it. Whatever it is, just normal professional activity.

MB If I were in your shoes I would conclude that they heard from somebody after the fact who had a lot of clout, and that was that. Somebody weighed in from some corner or other and that was that.

SC That may well be. I don’t know. All I know is that, in the 27 years that I have lived in New York, and in the writing time that I have had, and in the many publications I have been in, I have never had a situation in which something took place on that unprofessional of a level.

MB That would piss me off too.

SC But it is not a matter of being “pissed off,” what this is about is a problem within this community, which is that if they were at odds with something, an editor is supposed to tell me to try something else, because I wrote about a number of different things other than that for them, and the editor could have said to try another subject. That is not what happened.

Jazz Times’ version of the Stanley Crouch dismissal

JJM Addressing the issue of what is important to the reader, is it possible fans of jazz and readers of Jazz Times like Douglas’ integration of Balkan material into his sound because they find it intellectually stimulating, and are frankly not as concerned about the definition of “jazz” as they are about listening to or participating in the performance of music that is, to them, entertaining or intellectually rewarding?

MB By that question, it seems you shifted the ground back into a disinterested, critical discourse about the merits of certain kinds of music within certain kinds of musical traditions and the borders of those traditions, and whether something is inside or outside the borders or the limits of a certain tradition where you can still use the word “jazz” to apply to it. And that is a very interesting, intellectual debate. What strikes me is that at the outset of this conversation Stanley and Loren were both asserting that this debate is not happening. It sounds like the question you are asking is not getting asked, and that is part of the problem. Perhaps it is a matter of people jockeying for the “bennies” that are out there in the industry, and criticism has become a kind of shilling for whatever it is that is selling out there now. Is that the drift to where Stanley and Loren are going with this? I am accepting that there is no debate, and that is extremely unfortunate, and it sounds like this move on Stanley only makes the problem worse. What is to be done, to ask the question of Lenin? Why isn’t there a debate?

JJM I get that some musicians are frustrated that Stanley’s “camp” is restricting what can be determined as jazz. I suppose it is important to Douglas that his music be called “jazz,” and wishes to be known as a “jazz musician” whether he employs a traditional quartet or if he were to use Balkan folk material. My question to Stanley is how do musicians reach the heights of those attained by Louis Armstrong if their primary purpose is to emulate musicians from a previous era?

SC So now you think you are going to achieve the heights of Louis Armstrong by playing Balkan music? Is that it?

JJM I am not suggesting that, but Douglas’s employment of Balkan folk material is pretty radical, and if you turn the clock back 75 years, you can easily make the case that what Armstrong was doing was also pretty radical.

SC But, see, here is the problem I have. That is all of what’s going on now. In the column I wrote about Ornette Coleman’s contribution — and Coleman has never come “in,” he stayed “out there” where he was when he came to New York — I felt that there is such a strong blues quality in his sound and in his ability to swing. He is not somebody that you have to have a panel discussion about whether or not he is a jazz musician. I don’t care if somebody improvises or doesn’t improvise, whether they use Balkan music or not. That is not really the issue to me. The issue is that what these people want to do, and what the jazz critical establishment has concluded over the last twenty years or so, is that essentially there is no definition for “jazz.” I don’t believe that. I am not arguing that you can’t do whatever it is you want to do. The fundamentals of jazz are no more restrictive than the fundamentals of sex. There are certain things that have to go on in sex. Somebody may think that certain things may be too limiting, or that two people should be in two different rooms so they could actually do something different from what people usually do, whatever those things are. Now we are talking about telepathy or something different. All that, to me, is fraudulent. That whole idea of “cutting-edge” and all, that is just a bunch of bull shit to me, in the sense that the real achievements of the so-called “avant-garde” have never been built upon, quite frankly. The kind of melodic lines that Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry could play are not what most people attempt. The kinds of rhythmic complexities of Elvin Jones, a young Tony Williams or Ed Blackwell, or what Don Pullen figured out in playing that kind of clustered material and swing it with a rhythm section as he did with George Adams and Dannie Richmond, are not what people are trying. They don’t care to try. And it is not always because they can’t do it, or don’t choose to do it, but it is because the critical establishment is in this all-embracing posture. I don’t buy that.

LS I would like to add to that. Going back to the very interesting question concerning Armstrong. He was radical, yes, and it could be argued that what Douglas is doing with Balkan material is also radical because it does pretty much what Armstrong did, which is taking what existed and doing something radical with it. I just believe that talking about what Dave Douglas is doing and mentioning it in the same sentence with what Armstrong did is a big mistake, and one that has led to what Stanley has been referring to, which is a kind of “everything is everything” attitude — that jazz was about adding things together so you just keep adding until you get to where we are now, which is the question of what defines an idiom. And if you can’t define what an idiom is then what are we talking about? There is something called the jazz idiom, and I believe part of the problem is that a large part of the critical community may be claiming that Dave Douglas is the kind of artist who is actually an “idiom adder” or an “idiom changer,” and I feel that is, at best, premature. Talking about what Wynton Marsalis brings to the jazz idiom versus what Dave Douglas brings wouldn’t seem productive, but that is how the argument is always couched. As a musician myself, I have played on the same stage as Dave Douglas , just as I have with Marsalis, and from my own viewpoint, one thing that can be said is that Wynton is not into “musical necrophilia.” It is implicit in the typing of Wynton like that, as opposed to Dave Douglas.

MB With all due respect to Stanley’s reference to sex, I would rather refer to something more artistic, namely something like cubism. Cubism was a revolution in painting that occurred in a certain time and place. Other than Picasso, who was Spanish, most of the people were French. It took place in Paris. It is redolent of a certain time and place. So, there are complications following upon that, because it is a way of dealing with pictorial space, which to me is similar to jazz in lots of ways. It reconfigured the universe for visual artists, the way jazz reconfigured the musical universe for a lot of musicians and composers. No modern painter can ignore the legacy of cubism. An artist has to come to reckon with it in some way, and some draw upon it in a richer way than others. Others just go off and do something completely different; they don’t claim to be cubists, and they don’t claim to be in the cubist tradition, but in some broader sense they might claim to be modernist artists. I think part of it is that we have ourselves stuck on these words where any kind of music that isn’t an accepted mode of modernism in so-called “classical” or “serious” music is by default called “jazz.” So, all sorts of strains of musical modernism get fooled around with under this heading of “jazz,” because people want to be hip, they don’t want to be known as a boring concert musician. So if you are hip and you are doing a music act, you can say you are a “jazz musician.” I think there is a really good debate there. But it is also true that if somebody is painting in a way where they have obviously educated themselves in the pictorial language of cubism, it doesn’t necessarily mean they are a sort of “moldy fig,” trying to just paint exactly like Braque and Picasso. It means they are using that language in some contemporary sense. But why can’t jazz be talked about in this way?

SC My argument is this. All of those things that we get from European modernism and post-modernism are good for European things. But I believe that what musicians did in America is something that has to be assessed differently, because it doesn’t have any serious precedent at all in European music, and also, because it is a collective phenomenon. A painter is standing up in front of a canvas with an easel, and he is doing what he does or doesn’t do, and he is responding one way or another to a fairly long tradition of European painting. But, the whole phenomenon of what musicians actually do on a bandstand, and what they are bringing off when they are playing, is still in need of being assessed on a far higher level than it is. What I think misleads a number of musicians is that they get tied up in thinking about and trying to put themselves in the mental frame that, say, Picasso and Stravinsky and James Joyce did. But it seems to me that with musicians like Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Lester Young or Thelonious Monk, something different happened, and we haven’t gotten deeply enough into discussing what that was, and it does not need to “advance” along the terms of European stuff. What happened in European visual art is that eventually you got to the point where you are now. I was talking to a curator about the fact that so many modern painters or contemporary painters can’t paint or draw, and she said that is not important anymore.

MB But you can’t pin that on cubism.

SC I am not pinning anything on cubism, Martha. I am talking about this idea of a certain kind of progression.

MB But jazz went through all those things too

SC Wait a minute. Based on an increasing kind of abstraction that is further and further removed from the initial point. That is not Picasso’s fault. Picasso painted it every way he wanted to paint until he died. I am not talking about that. I am talking about this idea that progress is based upon an increasingly abstract removal from an initial point, and that is why you have certain kinds of things that are thought about in the jazz critical community — which is not populated by great thinkers, by the way. That is all I am saying. When they start talking about how “Bird did it” is like what Loren was saying. You can’t compare somebody like Dave Douglas to Louis Armstrong or to any of those major figures. The first thing, he is not, on his instrument, a major figure. Now, if you like what he thinks or he does, then you like what he thinks and what he does. But, I haven’t met one trumpet player yet who thinks that he is a major trumpet player. If we use Picasso as an example, we see what he could paint as a teenager, so he was already in another category. That’s all I mean.

LS All of these digressions I find fascinating, but what spawned this whole thing is that Stanley shone his light on to Dave Douglas and gave him credit for what he does, and that Francis Davis wrote this stuff, and, all that we know now is the next step is that he is out of the magazine, simply put, and that is where I want to keep my focus. That issue is much more important than even the issues we have been talking about.

MB Well, except that they are related. It is a question of how do you talk about jazz on an appropriately high level, where, as Stanley said, you are talking about what is really going on in the music. Critics borrow the critical language from modernism. I don’t see another one out there. That is the language in which all the art is talked about nowadays, post-modernism. Then you get into all that non-art, what I call “perverse-modernism,” which is non-art, anti-art. But to talk about something that is seriously worth talking about, you have an African American idiom and an African American musical language, and you have a critical language which does take its reference points from European modernism. Maybe there is a mismatch from the beginning, and we are never going to get out of this. What is the alternative?

LS It is as though Martin Williams never lived, or that we don’t have anyone to go back to for guidance. A handful of responsible people like Williams and Gunther Schuller and the early Leroi Jones dealt with the big changes and the controversies in the jazz world forty years ago. I am just saying that this is not the first time that we have had to cross this topic.

SC I think you hit upon it, Martha. What I was raising in that piece is that if the psychology of the people in the jazz establishment is that of rebellion against the middle class, then the things they like are the things that strike them as another aspect of rebellion against what they would consider middle class conventions, which is projected by middlebrows like Francis Davis. And when I talk about middle class, I am not even talking about whether somebody is a son of a coal miner or not, I am just talking about the way they think. Their whole thing goes back to that Beaudelaireian idea of scandalizing the middle class. Something I find fascinating is that, since the middle fifties, the idea of teenage rebellion against a restricting or emotionally, spiritually emaciated parent — which goes back to the Jim Backus father in Rebel Without a Cause — there is this idea that every generation of people had to define itself in opposition to the people who preceded them. In the process of writing my book about Charlie Parker, which I hope to have done in a couple years, one of the things I discovered is that Parker was not at war with people like Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins over their art. That wasn’t what he was trying to do. What he wanted was to be accepted as one of them. He wasn’t trying to get away from them, and he wasn’t trying to reject them. He heard something else he wanted to play, but he wanted to be one of those guys. The thing that fascinates me is the idea that you might be able to find your identity with great individual resonance through the affirmation of the tradition from which you come. It doesn’t mean that you have to dwell in the cliches of it. Individuality through affirmation is not even on the chart.

MB Now, I think we are touching upon it. This is something that has preoccupied me too. Compared to a lot of the other arts, the Afro-American arts — particularly the art of music — has this deep-seated kind of respect for, connection with, regard for, reverence for tradition. That sits alongside everybody looking to get a record contract. So, there is a kind of funny commercial motive for rejecting the past. But the rejection of the past and the rejection of the elders does not go as deep or as pervasive as it does in all of the European derived arts, because that is what modernism was all about. It was tied up in political revolution. Jazz went for that in the sixties, when it had a little fling with it, but I don’t think it really stuck. Jazz is deeply traditional in a way that a lot of the other arts are not. Is that a statement that you can agree with?

SC Yes, but when you say traditional

MB Yes, you are ruling out “moldy figism” and “musical necrophilia,” as Loren called it.

LS I just happen to have reread Gilbert Seldes’ “What is Jazz” chapter from The Seven Lively Arts, and I couldn’t remember whether he had written it in 1927 or ’28 or ’25. Well, I read it, and came away feeling that he was a man who at least had heard a Jelly Roll Morton or King Oliver recording, because he was writing with such insight about things. It turns out he wrote it in 1923, before Rhapsody in Blue, and he is already talking about Cole Porter and George Gershwin and all these guys. Anyway, the reason I bring it up is that jazz was always presented as something to slap your parents with in the same way that Plato wrote about, so I don’t think that is something that came into this later.

MB But, was he writing for a white audience?

LS Yes.

MB I think part of what Stanley is pointing out is the way whites use Afro-American culture. We all know this. We have all been around this.

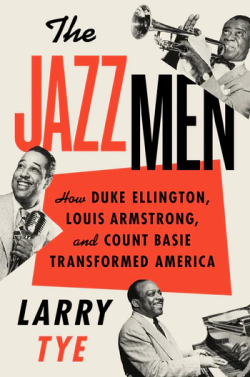

SC See, now we have hit the exact point of reference. What you just introduced, Martha, that is a lot of it. Because, one thing we know is that musicians like Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Lester Young were initially affirming something that their poor, black audience embraced. In other words, although they were truly avant-garde musicians — if we look at the conventions of Western music then they were avant-garde regardless of what kind of harmonies came with Stravinsky, Ravel or Debussy — in terms of how they were putting music together, they were still avant-garde musicians.

MB But they weren’t adversarial toward their audience.

SC And their audience didn’t see them as anything other than an affirmative group of guys who could play.

LS But this started to vitiate when the music they played stopped becoming functionally a dance music. People like Jimmy Heath say, “What is all this stuff about how people didn’t dance to bebop? I saw a thousand people dance to Charlie Parker at the Armory,” and I think that the way that people perceive what the musicians were doing was also colored by whether they were providing dance music. That was a significant part, in the way the musicians were thinking about it.

SC That great performance of Charlie Parker’s you refer to was at St. Nicholas Arena, and there are photographs in which you see all those people out there dancing, and this was to some of the “freest,” most inventive Charlie Parker we have on record. There he was, up on the bandstand, and people were dancing while he was playing all that stuff with Roy Haynes, “Mr. Rhythmic Displacement,” on the drums. So, the cliché doesn’t apply. That is not really what was going on.

MB Neither of you would deny, however, that at some point jazz did take a turn for the more elite, the more complex, the more difficult, and lost the kind of mass audience that it might have had in earlier times. We can argue about when that occurred, but, didn’t it occur?

SC But, I would argue this Martha, which is something that has fascinated me for years. When you listen to a King Oliver record and hear the kind of polyphony that they are dealing with, and compare it to the single line that Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell or John Coltrane played in front of a rhythm section, they are not playing anything that is more complex than the ensemble that Oliver was playing. The thing that fascinates me about jazz is that as it purportedly advances, people are able to play less. It was a normal thing in the twenties for three people in the twenties to actually play polyphony. Loren and damn near everybody now can tell you that is very difficult to find three guys who can get up on a bandstand and play really good polyphony, and that used to be a basic thing. So, you end up on one level ahead, the music moves or has been pushed or misled by some into an arena like abstract expressionism, where it becomes more and more about the person playing it than the relationship of what it is to the tradition from which it comes.

MB There are two ends to the animal when it comes to difficulty. There is the difficulty for the artist and there is the difficulty for the audience. I will admit that King Oliver’s music was difficult for the artist to play well, but it wasn’t that hard to listen to. In fact, it was a real pleasure to listen to. It took very little effort, and I think that is a principle that goes through all the arts. People confuse the idea of difficulty to do it well versus difficulty of access. At a certain point it seems that a lot of jazz music becomes difficulty of access. It is for me and I love the stuff. But I am more of an average listener than either Loren or Stanley, and I find some jazz just kind of, you know, difficult.

LS But that is because it lost the basic element of what fed it from its functionality, in terms of being able to dance to it. It kept it within the lines of what you are calling accessibility. There was a certain kind of melodic line, a certain kind of root rhythm, and as long as people were satisfying those needs, Ellington could get away with whatever he wanted to get away with because people could dance to it. Once it became untethered it kind of floated out and became free, and bands that kept jazz as a dance music going were thought to be commercial or sell-out. That wasn’t the case.

JJM Do jazz listeners want music that breaks with tradition?

SC First thing is, I think there is a big difference between what jazz listeners want and what jazz critics write about.

MB Of course.

SC For example, Dave Douglas has never become a popular player, nor has Cecil Taylor, David Ware, Matthew Shipp, Don Byron or any of these so-called “downtown musicians” the critics attempt to elevate. Douglas has some traditional things going for him that critics look for. He is white, blond, short and from the upper middle class. He knows the modernist language and does “projects.” As one guy pointed out to me, he is a critic’s delight because he does all these different projects and it gives critics something to write about. So, he gives the critics everything that they want, and furthermore, he provides the same thing that at a certain point so-called “West Coast Jazz” provided, which is a rebellion against the Negro. I am not backing off of that. These critics are basically saying that they have been following these Negroes for decades, and they do not have to do that anymore. They are saying it is time for us to start admitting white contributions to jazz were important, as if anyone other than some racist fools in the sixties ever pretended they weren’t important.

MB Where I started cheering for you in your essay, Stanley, is when you said it is about the destruction of the Negro aesthetic. To me, it is about a body of music and a set of musical practices that does not define progress in terms of self-destruction and self-immolation. Most of the arts have gone through this whole modernist/post-modernist wringer of defining progress as taking your art apart until there is not even any bones left — just picking it to death. For various reasons, a lot of people in jazz have essentially not gone into that, which is not to say they have stayed in the same place. But that is really hard for a lot of critics to grasp because they apply only one standard, and the one standard they apply is the radical modernist/post-modernist position of constantly taking the art apart, substituting something else for it, radically questioning and thinking about the art, and putting the conventions of the art and their borders into question. That is the oldest cliché, but it is constantly repeated, and if you apply that to today’s music scene, I guess this is the type of results you will have.

LS I would agree. Many of the musicians who these folks cite as mentors — whether it be a Coltrane or a Mingus — are the folks who mastered the idiom and were actually quite modest about their artistic intent. I realize the words “modest” and “Mingus” don’t go together, nonetheless, these artists were humble in the face of their origins and the tradition. And, as Stanley pointed out years ago, the avant-garde opened the door to these folks who were not masters of playing the blues in B flat but who were masters of the interview with the European jazz magazines, and they talked a whole bunch of stuff. I liked the point that Martha just put out, that what we are seeing is the end result of three or four decades of preparation.

SC I think there are many things happening in jazz today that are of great importance, and they are not being noticed because most of the people who write about jazz are only hooked up with this particular thing we are talking about. For instance, I recently heard Eric Reed’s septet at the Village Vanguard. They didn’t use any microphones there, not even on the piano. There was one microphone on the bandstand, and it was on the bass. Whether they played fast tunes that demanded a lot of fire from the drummer, or if they played ballads, this kid named Rodney Greene gave them all they needed, all of the drive, and he never drowned anyone out. To actually be able to go into a club and hear people who are not overamplified — who in fact aren’t amplified at all — and to hear a young drummer have that kind of control over his drums without sacrificing the fire that people want from a drummer in certain kinds of tunes, is to me a very important development. You have people like Eric Harland, Lewis Nash, Kenny Washington and Rodney Greene who are beginning to reject that whole overplaying, too loud conception that is part of the negative influence of pop music.

MB Yes, that’s an entirely different topic

SC Yes, but all I am saying is that the attitude of “too loud” that became “not loud enough” has had a big effect on jazz over the last thirty years. So, I think that these kinds of things like where people are actually hearing another kind of control that certain people are exhibiting is, to me, dramatically radical, especially in a period when you go into a club the size of the Village Vanguard and see a trumpet player in a quintet with the bell of his horn in a microphone. Why is that? You have all these monitors up on stage with these guys listening to themselves through these speakers. I was on a panel with Marsalis yesterday, and he said when musicians ask to turn up the monitor, they are not asking to hear the bass or the piano, they are always asking, “Give me more of me.” He was saying that these kinds of things move the music away from the kind of nuanced listening that you really need from one jazz musician to another on a bandstand in order to get a high quality performance. I feel that when you start seeing these sorts of things taking place, where musicians aren’t overplaying in whatever style they are playing, where they are starting to not play too loud, then they are starting to rebel against the volume. I heard Terence Blanchard play recently, and he never played into the microphone and the saxophone player didn’t either. So, I think there is something in the air now in which musicians are beginning to move away from that kind of microphone coating that we have become accustomed to in too many club situations, when you shouldn’t really have to use a bunch of microphones if the drummer has control of himself.

MB Now let me guess, if one of the critics walked into the club that night, they would say they were turning back the clock to the older days or something like that.

SC I don’t even know if they would notice that they didn’t have microphones. That is what I am saying.

LS They would say they are the Christian Scientists of jazz.

SC The other thing is something that Loren and I have talked about a number of times, where you could have a recording like Marcus Roberts’s big band record, Blues for the New Millennium, which features all kinds of new music, but missed the jazz critical radar screen. Why? Because since Roberts was in Marsalis’s band and worked for a while at Lincoln Center, he can’t be doing anything new. But that disc includes pieces with all kinds of rhythms he has these guys playing, and the overlays that develop where a guy will start playing a solo seemingly from behind the ensemble because he is not playing loud, and then he gets louder and louder and comes up into the foreground. He demonstrates all kinds of things that you never hear people doing today. On some Duke Ellington recordings you will hear Rex Stewart or somebody seeming to mutter his way into the foreground, but I just feel there are many different colors and combinations in the way that Marcus Roberts wrote the stuff for his record. Ted Nash, a saxophonist associated not only with Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra but also the “downtown guys,” said to me that he and the other guys in the band who were on that date expected that record to make some noise because it was so different. But the critical establishment didn’t even notice. To me, that is the kind of problem that we have. Many of the pieces Loren Schoenberg has commissioned from guys to write for his band don’t fit into a category that critics think Loren is in.

MB And that category is what?

LS Big band leader.

SC But he commissions contemporary pieces that are played extremely well by his band, and those pieces don’t get heard, because, if a critic sees his name, they don’t investigate the music because they have already decided if you want something “new,” you don’t go to Loren Schoenberg’s or Marcus Roberts’ band, because you are not going to get anything new there. A pianist like Bill Charlap is combining things from Ahmad Jamal, Bill Evans, Bud Powell and McCoy Tyner in a fresh, personal sense, and when he plays, he is not playing in a constrained style. There is something fresh in the way he plays. I just think there are things like this going on that are “A+ radical” according to the terms that the critical establishment themselves claim that they are interested in.

LS I would like to ask a question of both Martha and Stanley. It is a question that popped into my mind as we were talking about these issues. I am wondering if this would be a proper analogy or metaphor. Would it be fair to say that maybe one thing Wynton Marsalis was doing was asking jazz musicians to come back and have the ability to do the classic still-life painting of a bowl of fruit on a table? Was he saying that there is a point in art for centuries in which you get everybody confronting that table with that bowl of fruit on it, and at some point, with Jackson Pollock and those kinds of artists, that stuff goes out the window? And what Wynton is in a sense saying, do whatever you want, but I would like to know that you can also do this

MB Well, that is why I brought up cubism, because cubism was representational art, it was not abstract. It was an analytic way of seeing, and early cubism is kind of dry, but later cubism got very luscious and colorful and beautiful and gorgeous. The stuff they did in the thirties is as pretty as anything you care to see. It is very accessible that way, but they never would have gotten there if they hadn’t done that first spade-work, so to speak, and dug out what they were looking at. I am using cubism as an example, not because it partakes of all these other kinds of modernism which Stanley knows I don’t like, but because it is a thing that is still there. A serious painter who tries to take that on and deal in that language — whether it be French or Spanish or from Oklahoma — is dealing with the real aesthetic, and is dealing with something that has not gone away, and that is still fresh. You can’t just go and copy the old paintings, but there is so much there that hasn’t even been exhausted yet.

SC Do you know what? That is exactly the problem of jazz. A couple of weeks ago, I was talking to a drummer a named Bill Stewart, after I heard him play with Brad Mehldau and guitarist Peter Bernstein. Afterwards, we were hanging around talking about all of the things that just go by in jazz. There is so much material, it doesn’t make any difference what period you listen to, there are so many ideas, so many conceptions, so many things that musicians have played. They go into the studio one day, make a record, but then never make another one like it again. In the music there might be something that the piano player does, or something that is voiced in an Ellington arrangement or something Tadd Dameron did — you name it — and somehow jazz musicians just don’t seem to notice. I think that one of the great problems of jazz criticism in these magazines is they really are not very good at illuminating the varieties of possibilities within the music itself. I wrote one article for Jazz Times in which I was saying that there was a very small group of innovators in the forties and fifties, people like Charlie Parker, Mingus, Bud Powell, Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, Max Roach, Ray Brown, Oscar Pettiford. Now, what was everybody else supposed to do? Stop playing? One of the things I pointed out is that if you read jazz criticism, you would basically conclude that during the sixties, there were two major tenor sax players, John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, with Wayne Shorter being number three and maybe Albert Ayler being four. Now, all of that saxophone that people like Joe Henderson, Charlie Rouse, Hank Mobley, Lockjaw Davis, and Paul Gonsalves were playing; these are great jazz individualists, and why should a young saxophonist only know that there were only about four guys, when there were a number of tenor players who didn’t play like Coltrane or Sonny Rollins? They just fall off the map. Loren and I were talking earlier that if you don’t know jazz, you wouldn’t even know that Don Byas existed. You would hear there was Coleman Hawkins, then Lester Young came up with an alternative to Hawkins, then Dexter Gordon came along and then Charlie Parker. People like Don Byas just disappear in jazz, and they have something very rich to offer.

MB It’s the mentality in the visual arts that can be traced right back to a guy named Clement Greenberg, and that school of criticism. These folks came out of a Marxist tradition. They were not Stalinists, they were Trotskyites who believed in cutting-edge arts that would push the world toward a socialist future. Don’t ask me why they believed this, but they believed it. Greenberg’s most famous book of essays is Art and Culture, in which he praises all of the modernist artists of the hour, including Pollock and the abstract impressionists — anybody he can get his mitts on. They are always praised in the same terms. They are the avant-garde in the political sense, they are the leading cutting-edge not only of artistic change, but by implication of social and political change. This is the mentality that many of the critics work from. I don’t think half of these people can tell you where they get their ideas from, but that is where they get them from. There is a vacuum at the heart of it, because they don’t really think that the latest avant-garde jazz artist is going to cause a political revolution, but it is still this idea that there is a single cutting-edge, that history is moving forward, that we are marching into the future. It is all that way of thinking. I think somewhere in your column, Stanley, you talk about the idea of art always making progress. We need to question that idea. Is Mozart a mere precursor to Anton Webern? It doesn’t pay to look at art that way. That is not how it works.

SC That is something Eric Reed and I were talking about recently. He said he was talking to the pianist Claude Bolling in Europe, and asked him what happened to stride? How did stride disappear from jazz? Bolling said it disappeared because it was very hard to play, and when Bud Powell came along, piano players said, “Phew! Thank goodness we can get away from it. Now we do not have to deal with Fats Waller, Willie the Lion, and all of those guys.” He didn’t mean that Bud Powell couldn’t play what he was playing, but that is another example of what I meant a little earlier about these various elements of jazz that keep getting lopped off. At a certain point, people could play extremely well melodically through these tunes. In the beginning, some people could play by ear and they weren’t really harmonically sophisticated — Art Tatum, Coleman Hawkins and those kinds of guys. Then you have Don Byas, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker, who can play good through chord progression. Then you have people like Miles Davis, who put together the telling, poetic melodic style — the harmonic complexity. Now, though, we are at the point where all of that music has added up to people playing fifteen or twenty choruses of what sounds like exercises over one or two chords or vamps on every tune. So, you go to clubs and all of that music of Art Tatum, Charlie Parker, and the best of Coltrane, leads to you hearing today’s musicians play one tune after another on a vamp. It is just like the stuff narrowed itself down. What I have often attacked musicians and critics on is the narrowness of their vision, just like what you are saying, Martha. If it is the trickle-down Clement Greenberg vision, it is not a vision that parallels the realities of the music or the music’s greatest possibilities. The fact that during that period in the sixties, you had all of these people who were playing, who could really play. There was Stan Getz, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Gerry Mulligan, Art Farmer, Jim Hall, Ahmad Jamal, and so many others who could play, but when you pick up a jazz history book and get to the sixties, it is Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, blah, blah, blah. Those others were there. Believe me, I was on the scene, and there were plenty of other people who could definitely play, and they played all kinds of different ways. That is part of what we need in jazz criticism, is an openness — not so much just to novelty — but to creative ideas within the arena of jazz. See, it is very easy to take something that doesn’t relate to jazz and just put it in the middle of it and say this is my new project. An artist can say that he went to Bali and heard Balinese music, and decided to incorporate some gamelon on a particular piece. Ok, then, of course, he will get on the cover of Jazz Times. “Loren Schoenberg’s Gamelon Symphony, Written for Three Toothpicks.”

MB Well, you can incorporate different instruments into a musical language.

LS There is a guy out on the West Coast who did what Duke did on the Far East Suite, and what Dvorak did with his New World Symphony, taking inspiration from one place and then synthesizing it and putting it back within their own context. I think that is actually very close to what we are talking about with some of Dave Douglas’ things. Someone who has done what I think a lot of people are saying that Dave Douglas has done, but I believe who has done it better, is the person on the Coast, Anthony Brown, who interpreted Ellington’s Far East Suite, actually using some far east instruments on it. So, while reorchestrating Ellington’s Far East Suite, he kept it — and this is where it gets into the indefinable — within the jazz idiom.

But if I could just hijack this discussion for one moment back to what happened to Stanley at Jazz Times, which is one element here, and it also relates to Clement Greenburg, is the role of the critic as the person who is the artist’s sponsor. There is the perception of Stanley and Albert Murray as being the “men behind Wynton Marsalis,” as a result of Stanley’s mentoring of and friendship with him. Critics get upset by this, but they also want to have their guy. They want to be seen as the person behind a David Murray or a Dave Douglas or a whomever. The jazz critics and all of the others are missing that point, frankly. Of the jazz critics, Stanley Crouch is an invisible man to them. It’s a cliché, but it is true. They know about what Stanley writes in the Jazz Times magazine and gets these responses back, but they may not be aware of Notes of a Hanging Judge and his other books of essays, or of what he writes for the New York Daily News, or any of his other work. Consequently, they interpret pretty much anything that comes out of Stanley’s mouth as another shilling for his boy Wynton, as opposed to a serious critic giving him due for helping bring someone of Marsalis’ caliber up to the plate. Would you agree with some of that Stanley?

SC I would say this. That might be true. I don’t live in the world that those guys live in, so I don’t really know what their psychological relationship to me might happen to be. But I will say this. I have no doubt that there is great glee felt in the spiritual Mudville’s that they live in at the fact that they can take their little slingshots and shoot them at Marsalis because he now purportedly represents the establishment, which is what they think they are in rebellion against. As I said in “Putting the White Man in Charge,” a lot of these guys see themselves as some kind of neo-abolitionists and that their job is to rescue the Negro from the “plantation of no publicity” to the “Canada of attention,” perhaps resulting in record dates and maybe even an audience. Some of these critics talk about my relationship with Marsalis as an unprecedented relationship in which a writer has influence on a major musician. But finally, I would say this. What I find more than slightly remarkable — and I think Greg Osby would attest to this if anyone wants to ask him — is how Marsalis has been categorized as this backward looking musician, when in fact he has written and recorded so much music that were it to be released under the name of someone else, it would be perceived as some kind of rejuvenation of the avant-garde, or a reapplication of the kinds of successes of Ornette Coleman.

_______________________________

Roundtable conversation took place on May 4, 2003

_______________________________

Stanley Crouch products at Amazon.com

Martha Bayles products at Amazon.com

Loren Schoenberg products at Amazon.com

*

If you enjoyed this discussion, you may want to read our interviews with Stanley Crouch, Martha Bayles, and Loren Schoenberg.

Thanks to Paul Morris and Eric Busch, who assisted in the publication of “Blues For Clement Greenberg.”

If W Marsalis had the good old ‘Something to Say’ in music, there’d be no controversy over his work. A good discussion would go into fleshing out why some recordings give the grounded sense of a reason to exist, and most do not. Recordings are a good reference point because they parallel written musical scores – both are recordings of a musical impulse. But in our time, CDs are mainly advertising rather than art. If, as in the fine [visual] art area, criticism has almost disappeared, it’s because Adorno’s pessimism has come about, via our corporate culture, which W Marsalis represents very well, no doubt without his seeing it.